Battle of Poitiers

| Battle of Poitiers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Poitiers (1356) Eugène Delacroix | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000:[1]

| 11,000:[1]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minimal | 2,500 killed[2] 1,900 captured[2] | ||||||

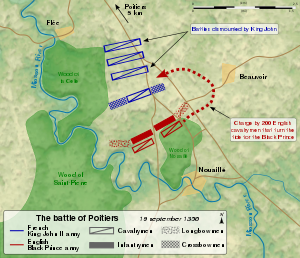

The Battle of Poitiers was a major English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It was fought on 19 September 1356 in Nouaillé, near the city of Poitiers in Aquitaine, western France. Edward, the Black Prince, led an army of English, Welsh, Breton and Gascon troops, many of them veterans of the Battle of Crécy. They were attacked by a larger French force led by King John II of France, which included allied Scottish forces. The French were heavily defeated; an English counter-attack captured King John, along with his youngest son, and much of the French nobility who were present.[3]

The effect of the defeat on France was catastrophic, leaving Dauphin Charles to rule the country. Charles faced populist revolts across the kingdom in the wake of the battle, which had destroyed the prestige of the French upper-class. The Edwardian phase of the war ended four years later in 1360, on favourable terms for England.

Poitiers was the second major English victory of the Hundred Years' War, coming a decade after the Battle of Crécy and about half a century before the Battle of Agincourt. The town and battle were often referred to as Poictiers in contemporaneous recordings, a name commemorated by several warships of the Royal Navy.[4]

Campaign background[edit]

Following the death of Charles IV of France in 1328, Philip, Count of Valois, had been chosen as his successor and crowned King Philip VI of France, superseding his closest male relative and legal successor, Edward III of England. Edward had been reluctant to pay homage to Philip in his role as Duke of Aquitaine, resulting in Philip's confiscation of those lands in 1337, an act which provoked war between the two nations. Three years later, Edward declared himself King of France. The war had begun well for the English. They had achieved naval domination early in the conflict at the Battle of Sluys in 1340,[5] devastated the south west of France during the Gascon campaign of 1345 and Lancaster's chevauchée the following year, inflicted a severe defeat on the French army at Crécy in 1346, and captured Calais in 1347.

In the late 1340s and early 1350s, the Black Death had devastated the population of Western Europe, even claiming Philip's wife, Queen Joan, as well as one of Edward's daughters, also named Joan; due to the disruption caused by the plague, all significant military campaigning was brought to a halt. Philip himself died in 1350, and was succeeded by his son, who was crowned King John II. In 1355, Edward III laid out plans for a second major campaign. His eldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, now an experienced soldier following the Crécy campaign, landed at Bordeaux in Aquitaine, leading his army on a march through southern France to Carcassonne. Unable to take the heavily fortified settlement, Edward withdrew back to Bordeaux. In early 1356, the Duke of Lancaster led an army through Normandy, while Edward led his army on a great chevauchée from Bordeaux on 8 August 1356.[6]

Edward's forces met little resistance, sacking numerous settlements, until they reached the Loire river at Tours. They were unable to take the castle or burn the town due to a heavy rainstorm. This delay allowed King John to attempt to pin down and destroy Edward's army. John, who had been besieging Breteuil in Normandy, organised the bulk of his army at Chartres to the north of Tours. In order to increase the speed of his army's march, he dismissed between 15,000 and 20,000 of his lower quality infantry, just as Edward turned back to Bordeaux.[7] The French rode hard and cut in front of the English army, crossing the bridge over the Vienne at Chauvigny. Learning of this, the Black Prince quickly moved his army south. Historians disagree over whether the outnumbered English commander was seeking battle or trying to avoid it.[8] In any case, after preliminary manoeuvres and failed negotiations for a truce, the two armies faced-off, both ready for battle, near Poitiers on Monday, 19 September 1356.

Battle[edit]

Preparations[edit]

Edward arrayed his army in a defensive posture among the hedges and orchards of the area, in front of the forest of Nouaillé. He deployed his front line of longbowmen behind a particularly prominent thick hedge, through which the road ran at right angles. The Earl of Douglas, commanding the Scottish division in the French army, advised King John that the attack should be delivered on foot, with horses being particularly vulnerable to English arrows. John heeded this advice, his army leaving its baggage behind and forming up on foot in front of the English. The English gained vantage points on the natural high ground in order for their longbowmen to have an advantage over the heavily armoured French troops.[citation needed]

English army[edit]

The English army was led by Edward, the Black Prince, and composed primarily of English and Welsh troops, though there was a large contingent of Gascon and Breton soldiers with the army. Edward's army consisted of approximately 2,000 longbowmen, 3,000 men-at-arms, and a force of 1,000 Gascon infantry.

Like the earlier engagement at Crécy, the power of the English army lay in the longbow, a tall, thick self-bow made of yew. Longbows had demonstrated their effectiveness against massed infantry and cavalry in several battles, such as Falkirk in 1298, Halidon Hill in 1333, and Crécy in 1346. Poitiers was the second of three major English victories of the Hundred Years' War attributed to the longbow, though its effectiveness against armoured French knights and men-at-arms has been disputed.[9][10][11]

Geoffrey the Baker wrote that the English archers under the Earl of Salisbury "made their arrows prevail over the [French] knights' armour",[12] but the bowmen on the other flank, under Warwick, were initially ineffective against the mounted French men-at-arms who enjoyed the double protection of steel plate armour and large leather shields.[13] Once Warwick's archers redeployed to a position where they could hit the unarmored sides and backs of the horses, however, they quickly routed the cavalry force opposing them. The archers were also unquestionably effective against common infantry, who did not have the wealth to afford plate armour.[14][15]

The English army was an experienced force; many archers were veterans of the earlier Battle of Crécy, and two of the key commanders, Sir John Chandos, and Captal de Buch were both experienced soldiers. The English army's divisions were led by Edward, the Black Prince, the Earl of Warwick, the Earl of Salisbury, Sir John Chandos and Captal de Buch.

French army[edit]

The French army was led by King John, and was composed largely of native French soldiers, though there was a contingent of German knights, and a large force of Scottish soldiers. The latter force was led by the Earl of Douglas and fought in the King's own division.[16] The French army at the battle comprised approximately 8,000 men-at-arms and 3,000 common infantry, though John had made the decision to leave behind the vast majority of his infantry, numbering up to 20,000, in order to overtake and force the English to battle.

The French army was arrayed in three "battles" or divisions. The vanguard was led by the Dauphin Charles, the second by the Duke of Orléans, while the third, the largest, was led by the King himself.

Negotiations[edit]

Prior to the battle, the local prelate, Cardinal Hélie de Talleyrand-Périgord attempted to broker a truce between the two sides, as recorded in the writings of the English commander, Sir John Chandos.[17] Attending the conference on the French side were King John, the Count of Tankerville, the Archbishop of Sens, and Jean de Talaru. Representing the English were the Earl of Warwick, the Earl of Suffolk, Bartholomew de Burghersh, James Audley, and Sir John Chandos. The English offered to hand over all of the war booty they had taken on their raids throughout France, as well as a seven-year truce. John, who believed his force could easily overwhelm the English, declined their proposal. John's counter suggestion that the Black Prince and his army should surrender was flatly rejected. An account of the meeting was recorded in the writings of the life of Sir John Chandos and were made in the final moments of a meeting of both sides in an effort to avoid the bloody conflict at Poitiers during The Hundred Years' War. The extraordinary narrative occurred just before that battle and reads as follows:

... The conference attended by the King of France, Sir John Chandos, and many other prominent people of the period, The King, to prolong the matter and to put off the battle, assembled and brought together all the barons of both sides. Of speech there he (the King) made no stint. There came the Count of Tancarville, and, as the list says, the Archbishop of Sens (Guillaume de Melun) was there, he of Taurus, of great discretion, Charny, Bouciquaut, and Clermont; all these went there for the council of the King of France. On the other side there came gladly the Earl of Warwick, the hoary-headed (white or grey headed) Earl of Suffolk was there, and Bartholomew de Burghersh, most privy to the Prince, and Audeley and Chandos, who at that time were of great repute. There they held their parliament, and each one spoke his mind. But their counsel I cannot relate, yet I know well, in very truth, as I hear in my record, that they could not be agreed, wherefore each one of them began to depart. Then said Geoffroi de Charny: 'Lords,' quoth he, 'since so it is that this treaty pleases you no more, I make offer that we fight you, a hundred against a hundred, choosing each one from his own side; and know well, whichever hundred be discomfited, all the others, know for sure, shall quit this field and let the quarrel be. I think that it will be best so, and that God will be gracious to us if the battle be avoided in which so many valiant men will be slain.[18]

Fighting begins[edit]

At the start of the battle, the English removed their baggage train from the field, prompting a hasty French assault, believing that what they saw was the English retreating.[19] The fighting began with a charge by a forlorn hope of 300 German knights, led by Jean de Clermont. The attack was a disaster, with many of the knights shot down or killed by English soldiery. According to Froissart, the English archers then shot their bows at the massed French infantry.[20] The Dauphin's division reached the English line. Exhausted by a long march in heavy equipment and harassed by the hail of arrows, the division was repulsed after approximately two hours of combat.[21]

The retreating vanguard collided with the advancing division of the Duke of Orléans, throwing the French army into chaos. Seeing the Dauphin's troops falling back, Orléans' division fell back in confusion. The third, and strongest, division led by the King advanced, and the two withdrawing divisions coalesced and resumed their advance against the English. Believing that the retreat of the first two French divisions marked the withdrawal of the French, Edward had ordered a force under Captal de Buch to pursue. Sir John Chandos urged the Prince to launch this force upon the main body of the French army under the King. Seizing upon this idea, Edward ordered all his men-at-arms and knights to mount for the charge, while de Buch's men, already mounted, were instructed to advance around the French left flank and rear.[22]

Capture of King John II[edit]

As the French advanced, the English launched their charge. With the French stunned by the attack, the impetus carried the English and Gascon forces right into their line. Simultaneously, de Buch's mobile reserve of mounted troops fell upon the French left flank and rear. With the French army fearful of encirclement, their cohesion disintegrated as many soldiers attempted to flee the field. Low on arrows, the English and Welsh archers abandoned their bows and ran forward to join the melée. Around this time, King John and his son, Philip the Bold, found themselves surrounded. As written by Froissart, an exiled French knight fighting with the English, Sir Denis Morbeke of Artois approached the king, requesting the King's surrender. The King is said to have replied, "To whom shall I yield me? Where is my cousin the Prince of Wales? If I might see him, I would speak with him". Denis replied; "Sir, he is not here; but yield you to me and I shall bring you to him". The king handed him his right gauntlet, saying; "I yield me to you".[23]

Following the surrender of the King and his son Philip, the French army broke up and left the field, ending the battle.[citation needed]

Aftermath[edit]

Following the battle, Edward resumed his march back to the English stronghold at Bordeaux. Jean de Venette, a Carmelite friar, vividly describes the chaos that ensued following the battle. The demise of the French nobility at the battle, only ten years from the catastrophe at Crécy, threw the kingdom into chaos. The realm was left in the hands of the Dauphin Charles, who faced popular rebellion across the kingdom in the wake of the defeat. Jean writes that the French nobles brutally repressed the rebellions, robbing, despoiling, and pillaging the peasants' goods. Mercenary companies hired by both sides added to the destruction, plundering the peasants and the churches.[24]

Charles, to the misery of the French peasantry, began to raise additional funds to pay for the ransom of his father, and to continue the war effort. Capitalising on the discontent in France, King Edward assembled his army at Calais in 1359 and led his army on a campaign against Rheims. Unable to take Rheims or the French capital, Paris, Edward moved his army to Chartres. Later, the Dauphin Charles offered to open negotiations, and Edward agreed.[citation needed]

The Treaty of Brétigny was ratified on 24 October 1360, ending the Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years' War. In it, Edward agreed to renounce his claims to the French throne, in exchange for full sovereign rights over an expanded Aquitaine and Calais, essentially restoring the former Angevin Empire.[25]

Nobles and men-at-arms present[edit]

English[edit]

Froissart states that these men fought with the Black Prince:

- Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick

- William de Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk

- William de Montacute, 2nd Earl of Salisbury

- John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford[26]

- Reginald de Cobham, 1st Baron Cobham

- Edward le Despencer, 1st Baron le Despencer[27]

- Lord James Audley

- Lord Peter Audley

- Thomas, Lord Berkeley

- Ralph, Lord Basset

- Fulk, Lord FitzWarin

- Lord Delaware

- Lord Manne

- John, Lord Willoughby

- Lord Bartholomew de Burghersh

- Thomas, Lord of Felton[28]

- Lord Richard of Pembroke

- Lord Stephen of Cosington

- Lord Bradetane

- Lord of Pommiers

- Lord of Languiran

- Captal of Buch

- Lord John the 69th of Caumont

- Lord de Lesparre

- Lord of Rauzan

- Lord of Condon

- Lord of Montferrand

- Lord of Landiras

- Lord Soudic of Latrau

- Lord Eustace d'Aubrecicourt

- Lord John of Ghistelles

- Lord Daniel Pasele

- Lord Denis of Amposta[29]

Another account states that John of Ghistelles perished at the Battle of Crécy so there is some ambiguity as to this individual.

French[edit]

Froissart states that these men fought with King John II:

- Dauphin Charles

- Louis I, Duke of Anjou

- John, Duke of Berry

- Philip the Bold – captured

- William Douglas, Duke of Touraine

- Geoffroi de Charny, carrier of the Oriflamme – killed

- Peter I, Duke of Bourbon – killed

- Walter VI, Count of Brienne and Constable of France – killed

- Jean de Clermont, Marshal of France – killed

- Arnoul d'Audrehem, King's Lieutenant in Artois, Picardy and the Boulonnais – wounded and captured

- John of Artois, Count of Eu – wounded and captured

- James I, Count of Marche and Ponthieu – captured

- Louis I, Count of Étampes – captured

- John II de Melun, Count of Tancarville – captured

- Renaud de Trie, Count of Dammartin – captured

- Count of Joinville – captured

- Guillaume de Melun, Archbishop of Sens – captured[30][31][32]

In popular culture[edit]

Arthur Conan Doyle's novel Sir Nigel features the Battle of Poitiers. The impoverished young squire Nigel Loring captures King John II of France in the melee. He fails to realise that he has accepted the surrender of the King of France, and so does not gain the King's ransom. However King John admits that Nigel was his vanquisher, so as reward Nigel is knighted by Edward, the Black Prince.

The battle appears in passing in A Knight's Tale when Count Adhemar is called back to the war.

Bernard Cornwell's novel 1356, the final novel in The Grail Quest series telling the story of Thomas of Hookton, dramatises the battle of Poitiers.

Michael Jecks's novel Blood of the Innocents, the final novel in The Hundred Years War trilogy, dramatises the campaign that culminates with the battle of Poitiers.

Coldplay's 2008 EP Prospekt's March uses the Battle of Poitiers painting by Eugène Delacroix as its album cover.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sumption 1999, p. 235.

- ^ a b Rogers 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Blockmans & Prevenier 1999, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Kendall B. Tarte (2007). Writing Places: Sixteenth-century City Culture and the Des Roches Salon. Associated University Presse. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-87413-965-5.

- ^ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 10

- ^ William W. Lace, The Hundred Years' War ISBN 978-1-56006-233-2, 1/1994

- ^ Jonathan Sumption, The Hundred Years' War: Vol. 2: Trial by Fire (London: Faber, 2001), pp. 223, 227–228

- ^ Rogers, Clifford J. (2000). War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewwer. pp. 348–373.

- ^ Strickland, Matthew; Hardy, Robert (2005). The Great Warbow: From Hastings to the Mary Rose. Sutton Publishing. pp. 272–278. ISBN 9780750931670.

- ^ Kaiser, Robert E. (December 2003). "Medieval Military Surgery". Medieval History Magazine. 1 (4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ^ Rogers, Clifford J. (1998). "The Efficacy of the Medieval Longbow: A Reply to Kelly DeVries". War in History. 5 (2): 233–42.

- ^ Edward Maunde Thompson, Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, (Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1889) p. 147 ("coegerunt sagittas armis militaribus prevalere")

- ^ Barber, Richard (1986). The Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-85115-435-2.

- ^ D. Green, The Battle of Poitiers 1356, (Tempus Publishing, Charleston, S.C., 2002)

- ^ Edward Maunde Thompson, Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, (Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1889) p. 304

- ^ William F. Skene, John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, (Edinburgh Edmonston and Douglas 1872), p. 365

- ^ Mildred K. Pope; Eleanor C. Lodge, Life of the Black Prince by the Herald of Sir John Chandos (Oxford, UK Clarendon Press 1910), p. 857

- ^ Life of the Black Prince by the Herald of Sir. John Chandos. edited from the Manuscript in Worchester College with Linguistic and Historical Notes, 1910. Not in Copyright p. 141-142

- ^ Urban, William L. (2006). Medieval Mercenaries: The Business of War. London: Greenhill Books. p. 99.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ^ https://www.britishbattles.com/one-hundred-years-war/battle-of-poitiers/

- ^ Oberhofer, Tom. "Battle of Poitiers". Eckerd College. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ This section reflects the traditional narrative of the battle, which relies to a substantial extent on the chronicle of Jean Froissart. For an alternative narrative based on the assumption that Froissart's narrative is not reliable, see Clifford J. Rogers, "The Battle of Poitiers, 1356" (English-language version of "La batalla de Poitiers (1356)", Desperta Ferro. Revista de historia militar y política. Antigua y medieval 38 (2016), 28–38)

- ^ Froissart, Jean (1910). "The Battle of Poitiers". In Eliot, Charles (ed.). Chronicle and Romance: Froissart, Malory, Holinshed. p. 52. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Jean Birdsall, Richard A. Newhall, The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (Columbia University Press 1953) p. 6

- ^ Hersch Lauterpacht, "Volume 20 of International Law Reports, Cambridge University Press, 1957, ISBN 0-521-46365-3, p. 118

- ^ Edward Maunde Thompson, Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, (Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1889) p. 248

- ^ David Nicolle, Graham Turner, Poitiers 1356: The Capture of a King (U.K. Osprey Publishing, 2004), p. 10

- ^ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). . Dictionary of National Biography. 18. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 308.

- ^ John Bourchier; G. C. Macaulay, Chronicles of Froissart, New York: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1948, p. 123

- ^ John Bourchier; G. C. Macaulay, Chronicles of Froissart, (New York Macmillan and Co., Ltd. 1948), p. 120

- ^ John Bourchier; G. C. Macaulay, Chronicles of Froissart, (New York Macmillan and Co., Ltd. 1948), pp. 104–106

- ^ Edward Maunde Thompson, Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, (Oxford at the Clarendon Press 1889) p. 297

Sources[edit]

- Belloc, Hilaire (1913). Poitiers, London: H. Rees. Via Internet Archive.

- Blockmans, Wim; Prevenier, Walter (1999). The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369–1530. Translated by Fackelman, Elizabeth. University of Pennsylvania Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, David (2004). The Battle of Poitiers 1356. ISBN 0-7524-2557-9.

- Hoskins, Peter (2011). In the Steps of the Black Prince, The Road to Poitiers, 1355–1356. Boydell&Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84383-611-7.

- Nicolle, David (2004). Poitiers 1356: The capture of a king (PDF). Oxford: Osprey Publishing (published 25 June 2004). ISBN 978-1-84176-516-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, Clifford J (2000). War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327-1360. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

- Rogers, Clifford J., ed. (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. Missing or empty

|title=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Rogers, Clifford J. "The Battle of Poitiers, 1356 (English-language version of "La batalla de Poitiers (1356)," Desperta Ferro. Revista de historia militar y política. Antigua y medieval 38 (2016), 28–38.)". Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). The Hundred Years War II: Trial by Fire. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13896-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Cornwell, Bernard: 1356, HarperCollins, 2012. ISBN 978-0007478200.

- Christian Cameron, The Ill-Made Knight, Orion, 2013.

- Witzel, Morgen; Livingstone, Marilyn (2018). The Black Prince and the Capture of a King: Poitiers 1356. Oxford: Casemate. ISBN 9781612004518.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Poitiers (1356). |

- The Chandos Herald: Life of the Black Prince includes a detailed account of the Battle of Poitiers.

- Froissart: The Chronicles of Poitiers (eBook) including "The Battle of Poitiers" in Charles W. Elliot (ed.): Chronicle and Romance: Froissart, Malory, Holinshed, 1910, The Harvard Classics. ISBN 9780766181885.

- On The Hundred Years War, a primary source written by Jean Froissart

- Great Battles: The Battle of Poitiers (myArmoury.com article)

- An animated map of the Battle of Poitiers. By David Crowther

- An animated map of the Poitiers Campaign. By David Crowther

No comments:

Post a Comment