Church (building)

A church building or church house, often simply called a church, is a building used for Christian religious activities, particularly for Christian worship services. The term is often used by Christians to refer to the physical buildings where they worship, but it is sometimes used as an analogy to refer to buildings of other religions.[1] In traditional Christian architecture, a church interior is often structured in the shape of a Christian cross. When viewed from plan view the vertical beam of the cross is represented by the center aisle and seating while the horizontal beam and junction of the cross is formed by the bema and altar.

Towers or domes are often added with the intention of directing the eye of the viewer towards the heavens and inspiring a range of thoughts and emotions in visitors and worshippers. Modern church buildings have a variety of architectural styles and layouts; many buildings that were designed for other purposes have now been converted for church use, and, conversely, many original church buildings have been put to other uses.

The earliest identified Christian church building was a house church founded between 233 and 256. From the 11th through the 14th centuries, a wave of building of cathedrals and smaller parish churches were erected across Western Europe. A cathedral is a church building, usually Roman Catholic, Protestant (including Anglican), Eastern Orthodox, or Oriental Orthodox, housing a cathedra, the formal name for the seat or throne of a presiding bishop.

Etymology[edit]

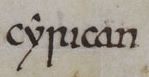

In Greek, the adjective kyriak-ós/-ē/-ón (κυριακόν) means "belonging, or pertaining, to a Kyrios" ("Lord"), and the usage was adopted by early Christians of the Eastern Mediterranean with regard to anything pertaining to the Lord Jesus Christ: hence "Kyriakós oíkos" (Kυριακός οίκος) ("house of the Lord", church), "Kyriakē" (Κυριακή) ("[the day] of the Lord", i.e. Sunday), or "Kyriakē proseukhē" (Greek: Κυριακή προσευχή) (the "Lord's Prayer").[2]

In standard Greek usage, the older word "ecclesia" (Greek: ἐκκλησία, ekklesía, literally "assembly", "congregation", or the place where such a gathering occurs) was retained to signify both a specific edifice of Christian worship (a "church"), and the overall community of the faithful (the "Church"). This usage was also retained in Latin and the languages derived from Latin (e.g. French église, Italian chiesa, Spanish iglesia, Portuguese igreja, etc.), as well as in the Celtic languages (Welsh eglwys, Irish eaglais, Breton iliz, etc.) and in Turkish (kilise).[2]

In the Germanic and some Slavic languages, the word kyriak-ós/-ē/-ón was adopted instead and derivatives formed thereof. In Old English the sequence of derivation started as "cirice", then Middle English "churche", and eventually "church" in its current pronunciation. German Kirche, Scots kirk, Russian церковь (tserkov), Serbo-Croatian crkva, etc., are all similarly derived.[3]

History[edit]

Antiquity[edit]

According to the New Testament, the earliest Christians did not build church buildings. Instead, they gathered in homes (Acts 17:5, 20:20, 1 Corinthians 16:19) or in Jewish places of worship, like the Second Temple or synagogues (Acts 2:46, 19:8). The earliest archeologically identified Christian church is a house church (domus ecclesiae), the Dura-Europos church, founded between 233 and 256.[4] In the second half of the 3rd century AD, the first purpose-built halls for Christian worship (aula ecclesiae) began to be constructed. Although many of these were destroyed early in the next century during the Diocletianic Persecution, even larger and more elaborate church buildings began to appear during the reign of the Emperor Constantine the Great.[5]

Medieval times[edit]

From the 11th through the 14th centuries, a wave of cathedral-building and construction of smaller parish churches occurred across Western Europe. Besides serving as a place of worship, the cathedral or parish church was frequently employed as a general gathering-place by the communities in which they were located, hosting such events as guild meetings, banquets, mystery plays, and fairs. Church grounds and buildings were also used for the threshing and storage of grain.[6]

Romanesque architecture[edit]

Between 1000 and 1200 the romanesque style became popular across Europe. While the term "Romanesque" refers to the tradition of Roman architecture, the trend in fact appeared throughout Western and Central Europe. The romanesque style is defined by large and bulky edifices that are typically made up of simple, compact, sparsely decorated geometric structures. Frequent features of the Romanesque church include circular arches, round or octagonal towers and cushion capitals on pillars. In the early romanesque era, coffering on the ceiling was fashionable, while later in the same era, groined vault gained popularity. Interiors widened and the motifs of sculptures took on more epic traits and themes.[7]

Gothic architecture[edit]

The Gothic style emerged around 1140 in Île-de-France and subsequently spread throughout Europe. Gothic churches lost the compact qualities of the romanesque era and decorations often contained symbolic and allegorical features. The first pointed arches, rib vaults and buttresses began to appear, all possessing geometric properties that reduced the need for large, rigid walls to ensure structural stability. This also permitted the size of windows to increase, producing brighter and lighter interiors. Nave ceilings became higher and pillars and steeples grew taller. Many architects used these developments to push the limits of structural possibility, an inclination which resulted in the collapse of several towers possessing designs that had unwittingly exceeded the boundaries of soundness. In Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain, it became popular to build hall churches, a style in which every vault would be built to the same height.

Gothic cathedrals were lavishly designed, as in the romanesque era, and many share romanesque traits. However, several also exhibit unprecedented degrees of detail and complexity in decoration. The Notre-Dame de Paris and Notre-Dame de Reims in France, as well as the San Francesco d'Assisi in Palermo, and the Salisbury Cathedral and Wool Church in England demonstrate the elaborate stylings characteristic of Gothic cathedrals.

Some of the most well-known gothic churches remained unfinished for centuries, after the gothic style fell out of popularity. The construction of the Cologne Cathedral, which was begun in 1248, halted in 1473, and not resumed until 1842 is one such example.[8]

Renaissance[edit]

In the 15th and 16th century, the change in ethics and society due to the Renaissance and the Reformation also influenced the building of churches. The common style was much like the gothic style, but in a simplified way. The basilica was not the most popular type of church anymore, but instead hall churches were built. Typical features are columns and classical capitals.[9]

In Protestant churches, where the proclamation of God's Word is of special importance, the visitor's line of view is directed towards the pulpit.

Baroque architecture[edit]

The baroque style was first used in Italy around 1575. From there it spread to the rest of Europe and to the European colonies. During the baroque era, the building industry increased heavily. Buildings, even churches, were used as indicators for wealth, authority and influence. The use of forms known from the renaissance were extremely exaggerated. Domes and capitals were decorated with moulding and the former stucco-sculptures were replaced by fresco paintings on the ceilings. For the first time, churches were seen as one connected work of art and consistent artistic concepts were developed. Instead of long buildings, more central-plan buildings were created. The sprawling decoration with floral ornamentation and mythological motives raised until about 1720 to the rococo era.[10]

The Protestant parishes preferred lateral churches, in which all the visitors could be as close as possible to the pulpit and the altar.

Architecture[edit]

A common architecture for churches is the shape of a cross[11] (a long central rectangle, with side rectangles, and a rectangle in front for the altar space or sanctuary). These churches also often have a dome or other large vaulted space in the interior to represent or draw attention to the heavens. Other common shapes for churches include a circle, to represent eternity, or an octagon or similar star shape, to represent the church's bringing light to the world. Another common feature is the spire, a tall tower on the "west" end of the church or over the crossing.

Another common feature of many Christian churches is the eastwards orientation of the front altar.[12] Often, the altar will not be oriented due east, but in the direction of sunrise. This tradition originated in Byzantium in the 4th century, and became prevalent in the West in the 8th to 9th century. The old Roman custom of having the altar at the west end and the entrance at the east was sometimes followed as late as the 11th century even in areas of northern Europe under Frankish rule, as seen in Petershausen (Constance), Bamberg Cathedral, Augsburg Cathedral, Regensburg Cathedral, and Hildesheim Cathedral.[13]

Types[edit]

Basilica[edit]

The Latin word basilica (derived from Greek, Basiliké Stoà, Royal Stoa) was originally used to describe a Roman public building (as in Greece, mainly a tribunal), usually located in the forum of a Roman town.[14][15]

After the Roman Empire became officially Christian, the term came by extension to refer to a large and important church that has been given special ceremonial rights by the Pope. Thus the word retains two senses today, one architectural and the other ecclesiastical.

Cathedral[edit]

A cathedral is a church, usually Catholic, Anglican, Oriental Orthodox or Eastern Orthodox, housing the seat of a bishop. The word cathedral takes its name from cathedra, or Bishop's Throne (In Latin: ecclesia cathedralis). The term is sometimes (improperly) used to refer to any church of great size.

A church that has the function of cathedral is not necessarily a large building. It might be as small as Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, England, Sacred Heart Cathedral in Raleigh, United States, or Chur Cathedral in Switzerland. However, frequently, the cathedral along with some of the abbey churches, was the largest building in any region.

Pilgrimage church[edit]

A pilgrimage church is a church to which pilgrimages are regularly made, or a church along a pilgrimage route, often located at the tomb of a saints, or holding icons or relics to which miraculous properties are ascribed, the site of Marian apparitions, etc.

Conventual church[edit]

A conventual church (or monastery church, minster, katholikon) is the main church building in a Christian monastery or abbey.

Collegiate church[edit]

A collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons, which may be presided over by a dean or provost. Collegiate churches were often supported by extensive lands held by the church, or by tithe income from appropriated benefices. They commonly provide distinct spaces for congregational worship and for the choir offices of their clerical community.

Evangelical church structures[edit]

The architecture of evangelical places of worship is mainly characterized by its sobriety.[16][17] The Latin cross is one of the only spiritual symbols that can usually be seen on the building of an evangelical church and that identifies the place's belonging.[18][19] Some services take place in theaters, schools or multipurpose rooms, rented for Sunday only.[20][21][22] Because of their understanding of the second of the Ten Commandments, evangelicals do not have religious material representations such as statues, icons, or paintings in their places of worship.[23][24] There is usually a baptistery on the stage of the auditorium (also called sanctuary) or in a separate room for baptisms by immersion.[25][26]

Alternative buildings[edit]

Old and disused church buildings can be seen as an interesting proposition for developers as the architecture and location often provide for attractive homes[27] or city centre entertainment venues[28] On the other hand, many newer churches have decided to host meetings in public buildings such as schools,[29] universities,[30] cinemas[31] or theatres.[32]

There is another trend to convert old buildings for worship rather than face the construction costs and planning difficulties of a new build. Unusual venues in the UK include a former tram power station,[33] a former bus garage,[34] an former cinema and bingo hall,[35] a former Territorial Army drill hall,[36] and a former synagogue.[37] A windmill has also been converted into a church at Reigate Heath.

There has been an increase in partnerships between church management and private real estate companies to redevelop church properties into mixed uses. While it has garnered criticism from some, the partnership offers congregations the opportunity to increase revenue while preserving the property.[38]

See also[edit]

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- Cathedral floorplan

- Chapel

- Church architecture

- Cowboy church

- Duomo

- Eastern Orthodox church architecture

- House church

- List of basilicas

- Lists of cathedrals

- List of highest church naves

- List of largest church buildings in the world

- List of oldest church buildings

- List of tallest church buildings in the world

- List of Unitarian, Universalist, and Unitarian Universalist churches

- Mandir

- Meeting house

- Monastery

- Mosque

- Palisade church

- Place of worship

- Post church

- Pub church

- Polish Cathedral style

- Shrine

- Simultaneum

- Stave church

- Synagogue

- Tabernacle (Methodist)

- Temple

References[edit]

- ^ Use of the term "The Manichaean Church", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b "Church". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "THE CORRECT MEANING OF "CHURCH" AND "ECCLESIA"". www.aggressivechristianity.net. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Snyder, Graydon F. (2003). Ante Pacem: Archaeological Evidence of Church Life Before Constantine. Mercer University Press. p. 128.

- ^ Hartog, Paul (ed.). The Contemporary Church and the Early Church: Case Studies in Ressourcement. Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1606088999. (Chapter 3)

- ^ Levy. Cathedrals and the Church. p. 12.

- ^ Toman, Rolf (30 April 2015). Romanesque: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting. h.f.ullmann. ISBN 9783848008407.

- ^ Frankl, Paul; Crossley, Paul (2000). Gothic Architecture. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300087993.

- ^ Anderson, Christy (28 February 2013). Renaissance Architecture. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780192842275.

- ^ Merz, Jörg Martin (2008). Pietro Da Cortona and Roman Baroque Architecture. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300111231.

- ^ Petit, John Louis (1841). Remarks on Church Architecture ... J. Burns.

- ^ "The Institute for Sacred Architecture | Articles | Sacred Places: The Significance of the Church Building". www.sacredarchitecture.org. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Heinrich Otte, Handbuch der kirchlichen Kunst-Archäologie des deutschen Mittelalters (Leipzig 1868), p. 12

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2013 ISBN 978-0-19968027-6), p. 117

- ^ "The Institute for Sacred Architecture - Articles- The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture".

- ^ Peter W. Williams, Houses of God: Region, Religion, and Architecture in the United States, University of Illinois Press, USA, 2000, p. 125

- ^ Murray Dempster, Byron D. Klaus, Douglas Petersen, The Globalization of Pentecostalism: A Religion Made to Travel, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2011, p. 210

- ^ Mark A. Lamport, Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South, Volume 2, Rowman & Littlefield, USA, 2018, p. 32

- ^ Anne C. Loveland, Otis B. Wheeler, From Meetinghouse to Megachurch: A Material and Cultural History, University of Missouri Press, USA, 2003, p. 149

- ^ Annabelle Caillou, Vivre grâce aux dons et au bénévolat, ledevoir.com, Canada, November 10, 2018

- ^ Helmuth Berking, Silke Steets, Jochen Schwenk, Religious Pluralism and the City: Inquiries into Postsecular Urbanism, Bloomsbury Publishing, UK, 2018, p. 78

- ^ George Thomas Kurian, Mark A. Lamport, Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States, Volume 5, Rowman & Littlefield, USA, 2016, p. 1359

- ^ Cameron J. Anderson, The Faithful Artist: A Vision for Evangelicalism and the Arts, InterVarsity Press, USA, 2016, p. 124

- ^ Doug Jones, Sound of Worship, Taylor & Francis, USA, 2013, p. 90

- ^ William H. Brackney, Historical Dictionary of the Baptists, Scarecrow Press, USA, 2009, p. 61

- ^ Wade Clark Roof, Contemporary American Religion, Volume 1, Macmillan, UK, 2000, p. 49

- ^ Alexander, Lucy (14 December 2007). "Church conversions". The Times. London. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Site design and technology by Lightmaker.com. "quality food and drink". Pitcher and Piano. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to the Family Church Christchurch Dorset". The Family Church Christchurch. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to The Hope Church, Manchester... A Newfrontiers Church based in Salford, Greater Manchester UK". The-hope.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Jubilee Church London". jubileechurchlondon.org.

- ^ "Welcome to Hillsong Church". Hillsong Church UK. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "CITY CHURCH NEWCASTLE & GATESHEAD – enjoying God...making friends...changing lives – Welcome". City-church.co.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ "Aylsham Community Church". Aylsham Community Church. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Hall, Reg (2004). Things are different now: A short history of Winchester Family Church. Winchester: Winchester Family Church. p. 11.

- ^ "ABOUT". www.barnabascommunitychurch.com. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "Where We Meet". City Church Sheffield. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Friedman, Robyn A. "Churches Redeveloping Properties to Give Them New Life". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Levy, Patricia (2004). Cathedrals and the Church. Medieval World. North Mankato, MN: Smart Apple Media. ISBN 1-58340-572-0.

- Krieger, Herman (1998). Churches ad hoc. PhotoZone Press.

- Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain, Qu'est-ce qu'une église ?, Gallimard, Paris, 333 p., 2010.

- Gendry Mickael, L'église, un héritage de Rome, Essai sur les principes et méthodes de l'architecture chrétienne, Religions et Spiritualité, collection Beaux-Arts architecture religion, édition Harmattan 2009, 267 p.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Church (building) |

| Look up church in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia – Ecclesiastical Buildings

- New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia – The Church

- Prairie Churches Documentary produced by Prairie Public Television

- Iowa Places of Worship Documentary produced by Iowa Public Television

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

No comments:

Post a Comment