Ed Sullivan

Ed Sullivan | |

|---|---|

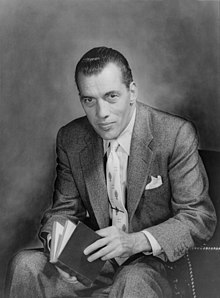

Ed Sullivan in 1955 | |

| Born | Edward Vincent Sullivan September 28, 1901 Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 13, 1974 (aged 73) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery |

| Occupation | Television host, reporter, newspaper columnist |

| Years active | 1932–1974 |

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) |

| Spouse(s) | Sylvia Weinstein (m. 1930; died 1973) |

| Children | Elizabeth 'Betty' Sullivan Precht [1] |

Edward Vincent Sullivan (September 28, 1901 – October 13, 1974) was an American television personality, impresario,[2] sports and entertainment reporter, and syndicated columnist for the New York Daily News and the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate. He is principally remembered as the creator and host of the television variety program The Toast of the Town, later popularly—and, eventually, officially—renamed The Ed Sullivan Show. Broadcast for 23 years from 1948 to 1971, it set a record as the longest-running variety show in US broadcast history.[3] "It was, by almost any measure, the last great TV show," said television critic David Hinckley. "It's one of our fondest, dearest pop culture memories."[4]

Sullivan was a broadcasting pioneer at many levels during television's infancy. As TV critic David Bianculli wrote, "Before MTV, Sullivan presented rock acts. Before Bravo, he presented jazz and classical music and theater. Before the Comedy Channel, even before there was the Tonight Show, Sullivan discovered, anointed and popularized young comedians. Before there were 500 channels, before there was cable, Ed Sullivan was where the choice was. From the start, he was indeed 'the Toast of the Town'."[5] In 1996, Sullivan was ranked number 50 on TV Guide's "50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time".[6]

Early life and career[edit]

Edward Vincent Sullivan was born on September 28, 1901 in Harlem, New York City, the son of Elizabeth F. (née Smith) and Peter Arthur Sullivan, a customs house employee. He grew up in Port Chester, New York where the family lived in a small red brick home at 53 Washington Street.[7] He was of Irish descent.[8][9] The entire family loved music, and someone was always playing the piano or singing. A phonograph was a prized possession; the family loved playing all types of records on it. Sullivan was a gifted athlete in high school, earning 12 athletic letters at Port Chester High School. He played halfback in football; he was a guard in basketball; in track he was a sprinter. With the baseball team, Sullivan was catcher and team captain, and he led the team to several championships. Baseball made an impression on him that would affect his career as well as the culture of America. Sullivan noted that, in the state of New York, regarding high school sports, then integration was taken for granted: "When we went up into Connecticut, we ran into clubs that had Negro players. In those days this was accepted as commonplace; and so, my instinctive antagonism years later to any theory that a Negro wasn't a worthy opponent or was an inferior person. It was just as simple as that."[10]

Sullivan landed his first job at The Port Chester Daily Item, a local newspaper for which he had written sports news while in high school and then joined the paper full-time after graduation. In 1919, he joined The Hartford Post. The newspaper folded in his first week there, but he landed another job on The New York Evening Mail as a sports reporter. After The Evening Mail closed in 1923, he bounced through a series of news jobs with The Associated Press, The Philadelphia Bulletin, The Morning World, The Morning Telegraph, The New York Bulletin and The Leader. Finally, in 1927, Sullivan joined The Evening Graphic, first as a sports writer, and then as a sports editor. In 1929, when Walter Winchell moved to The Daily Mirror, Sullivan was made Broadway columnist. He left the Graphic for the city's largest tabloid, the New York Daily News. His column, "Little Old New York", concentrated on Broadway shows and gossip, as Winchell's had; and, like Winchell, he did show-business news broadcasts on radio. Again echoing Winchell, Sullivan took on yet another medium in 1933 by writing and starring in the film Mr. Broadway, which has him guiding the audience around New York nightspots to meet entertainers and celebrities. Sullivan soon became a powerful starmaker in the entertainment world himself, becoming one of Winchell's main rivals, setting the El Morocco nightclub in New York as his unofficial headquarters against Winchell's seat of power at the nearby Stork Club. Sullivan continued writing for The News throughout his broadcasting career, and his popularity long outlived Winchell's. In the late 60's, however, Sullivan praised Winchell's legacy in a magazine interview, leading to a major reconciliation between the longtime adversaries.

Throughout his career as a columnist, Sullivan had dabbled in entertainment—producing vaudeville shows with which he appeared as master of ceremonies in the 1920s and 1930s, directing a radio program over the original WABC (now WCBS) and organizing benefit reviews for various causes.

Radio[edit]

In 1941, Sullivan was host of the Summer Silver Theater, a variety program on CBS, with Will Bradley as bandleader and a guest star featured each week.[11]

Television[edit]

In 1948, Marlo Lewis, a producer, got the CBS network to hire Sullivan to do a weekly Sunday-night TV variety show, Toast of the Town, which later became The Ed Sullivan Show. Debuting in June 1948, the show was originally broadcast from the Maxine Elliott Theatre on West 39th Street in New York City. In January 1953, it moved to CBS-TV Studio 50, at 1697 Broadway (at 53rd Street) in New York City, which in 1967 was renamed the Ed Sullivan Theater (and was later the home of the Late Show with David Letterman and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert). Studio 50 was formerly a CBS Radio studio, from 1936 to 1953, and before that was the legitimate Hammerstein Theatre, built in 1927.[12]

Television critics gave the new show and its host poor reviews.[13] Harriet Van Horne alleged that "he got where he is not by having a personality, but by having no personality." (The host wrote to the critic, "Dear Miss Van Horne: You bitch. Sincerely, Ed Sullivan.") Sullivan had little acting ability; in 1967, 20 years after his show's debut, Time magazine asked, "What exactly is Ed Sullivan's talent?" His mannerisms on camera were so awkward that some viewers believed the host suffered from Bell's palsy.[14] Time in 1955 stated that Sullivan resembled

a cigar-store Indian, the Cardiff Giant and a stone-faced monument just off the boat from Easter Island. He moves like a sleepwalker; his smile is that of a man sucking a lemon; his speech is frequently lost in a thicket of syntax; his eyes pop from their sockets or sink so deep in their bags that they seem to be peering up at the camera from the bottom of twin wells.[13]

The magazine concluded, however, that "Yet, instead of frightening children, Ed Sullivan charms the whole family." Sullivan appeared to the audience as an average guy who brought the great acts of show business to their home televisions. "Ed Sullivan will last", comedian Fred Allen said, "as long as someone else has talent",[13] and frequent guest Alan King said, "Ed does nothing, but he does it better than anyone else in television."[14] He had a newspaperman's instinct for what the public wanted, and programmed his variety hours with remarkable balance. There was something for everyone.[13] A typical show would feature a vaudeville act (acrobats, jugglers, magicians, etc.), one or two popular comedians, a singing star, a hot jukebox favorite, a figure from the legitimate theater, and for the kids, a visit with puppet "Topo Gigio, the little Italian mouse", or a popular athlete. The bill was often international in scope, with many European performers augmenting the American artists.[14]

Sullivan had a healthy sense of humor about himself and permitted—even encouraged—impersonators such as John Byner, Frank Gorshin, Rich Little, and especially Will Jordan to imitate him on his show. Johnny Carson also did a fair impression, and even Joan Rivers imitated Sullivan's unique posture. The impressionists exaggerated his stiffness, raised shoulders, and nasal tenor phrasing, along with some of his commonly used introductions, such as "And now, right here on our stage ...", "For all you youngsters out there ...", and "a really big shew" (his pronunciation of the word "show"). Will Jordan portrayed Sullivan in the films I Wanna Hold Your Hand, The Buddy Holly Story, The Doors, Mr. Saturday Night, Down with Love, and in the 1979 TV movie Elvis.

Sullivan inspired a song in the musical Bye Bye Birdie,[15] and in 1963, appeared as himself in the film.

In 1954, Sullivan was a co-host on a memorable TV musical special, General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein.[16]

Sullivan, the starmaker[edit]

In the 1950s and 1960s, Sullivan was a respected starmaker because of the number of performers who became household names after appearing on the show. He had a knack for identifying and promoting top talent and paid a great deal of money to secure that talent for his show. Sullivan was quoted as saying "In the conduct of my own show, I've never asked a performer his religion, his race or his politics. Performers are engaged on the basis of their abilities. I believe that this is another quality of our show that has helped win it a wide and loyal audience.[17]"

Although Sullivan was wary of Elvis Presley's "bad boy" image, and initially said that he would never book him, Presley became too big a name to ignore; in 1956, Sullivan signed him for three appearances.[15][18] In August 1956, Sullivan was injured in an automobile accident near his country home in Southbury, Connecticut, and missed Presley's first appearance on September 9. Charles Laughton wound up introducing Presley on the Sullivan hour.[19] When Ed returned to the show, audiences noticed a change in his voice. After Sullivan got to know Presley personally, he made amends by telling his audience, "This is a real decent, fine boy."[20]

Sullivan's failure to scoop the TV industry with Presley made him determined to get the next big sensation first. In November 1963, while in Heathrow Airport, Sullivan witnessed Beatlemania as the band returned from Sweden. At first he was reluctant to book the Beatles because the band did not have a commercially successful single released in the US at the time, but at the behest of a friend, legendary impresario Sid Bernstein, Sullivan signed the group. Their initial Sullivan show appearance on February 9, 1964, was the most-watched program in TV history to that point, and remains one of the most-watched programs of all time.[21] The Beatles appeared three more times in person, and submitted filmed performances afterwards. The Dave Clark Five, who claimed a "cleaner" image than the Beatles, made 13 appearances on the show, more than any other UK group.

Unlike many shows of the time, Sullivan asked that most musical acts perform their music live, rather than lip-synching to their recordings.[22] Examination of performances show that exceptions were made, as when a microphone could not be placed close enough to a performer for technical reasons. An example was B.J. Thomas' 1969 performance of "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head", in which actual water was sprinkled on him as a special effect. In 1969, Sullivan presented the Jackson 5 with their first single "I Want You Back", which ousted the B.J. Thomas song from the top spot of Billboard's pop charts.

Sullivan had an appreciation for African American talent. According to biographer Gerald Nachman, "Most TV variety shows welcomed 'acceptable' black superstars like Louis Armstrong, Pearl Bailey and Sammy Davis Jr. ... but in the early 1950s, long before it was fashionable, Sullivan was presenting the much more obscure black entertainers he had enjoyed in Harlem on his uptown rounds— legends like Peg Leg Bates, Pigmeat Markham and Tim Moore ... strangers to white America."[23] He hosted pioneering TV appearances by Bo Diddley, the Platters, Brook Benton, Jackie Wilson, Fats Domino, and numerous Motown acts, including the Supremes, who appeared 17 times.[24] As the critic John Leonard wrote, "There wasn't an important black artist who didn't appear on Ed's show."[25]

He defied pressure to exclude African American entertainers, and to avoid interacting with them when they did appear. "Sullivan had to fend off his hard-won sponsor, Ford's Lincoln dealers, after kissing Pearl Bailey on the cheek and daring to shake Nat King Cole's hand," Nachman wrote.[26] According to biographer Jerry Bowles, "Sullivan once had a Ford executive thrown out of the theatre when he suggested that Sullivan stop booking so many black acts. And a dealer in Cleveland told him 'We realize that you got to have niggers on your show. But do you have to put your arm around Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson at the end of his dance?' Sullivan had to be physically restrained from beating the man to a pulp."[27] Sullivan later raised money to help pay for Robinson's funeral.[28] "As a Catholic, it was inevitable that I would despise intolerance, because Catholics suffered more than their share of it," he told an interviewer. "As I grew up, the causes of minorities were part and parcel of me. Negroes and Jews were the minority causes closest at hand. I need no urging to take a plunge in and help."[29]

At a time when television had not yet embraced Country and Western music, Sullivan featured Nashville performers on his program. This, in turn, paved the way for shows such as Hee Haw, and variety shows hosted by Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, and other country singers.[30] The act that appeared most frequently through the show's run was the Canadian comedy duo of Wayne & Shuster, who made 67 appearances between 1958 and 1969.

Sullivan appeared as himself on other television programs, including an April 1958 episode of the Howard Duff and Ida Lupino CBS sitcom, Mr. Adams and Eve. On September 14, 1958, Sullivan appeared on What's My Line? as a mystery guest, and showed his comedic side by donning a rubber mask. In 1961, Sullivan was asked by CBS to fill in for an ailing Red Skelton on The Red Skelton Show. Sullivan took Skelton's roles in the various comedy sketches; Skelton's hobo character "Freddie the Freeloader" was renamed "Eddie the Freeloader."

Personality[edit]

Sullivan was quick to take offense if he felt that he had been crossed, and he could hold a grudge for a long time. As he told biographer Gerald Nachman, "I'm a pop-off. I flare up, then I go around apologizing."[31] "Armed with an Irish temper and thin skin," wrote Nachman, "Ed brought to his feuds a hunger for combat fed by his coverage of, and devotion to, boxing."[32] Bo Diddley, Buddy Holly, Jackie Mason, and Jim Morrison were parties to some of Sullivan's most storied conflicts.

For his second Sullivan appearance in 1955, Bo Diddley planned to sing his namesake hit, "Bo Diddley", but Sullivan told him to perform Tennessee Ernie Ford's song "Sixteen Tons". "That would have been the end of my career right there," Diddley told his biographer,[33] so he sang "Bo Diddley" anyway. Sullivan was enraged: "You're the first black boy that ever double-crossed me on the show," Diddley quoted him as saying. "We didn't have much to do with each other after that."[34] Later, Diddley resented that Elvis Presley, whom he accused of copying his revolutionary style and beat, received the attention and accolades on Sullivan's show that he felt were rightfully his. "I am owed," he said, "and I never got paid."[35] "He might have," wrote Nachman, "had things gone smoother with Sullivan."[36]

Buddy Holly and the Crickets first appeared on the Sullivan show in 1957 to an enthusiastic response. For their second appearance in January 1958, Sullivan considered the lyrics of their chosen number "Oh, Boy!" too suggestive, and ordered Holly to substitute another song. Holly responded that he had already told his hometown friends in Texas that he would be singing "Oh, Boy!" for them. Sullivan, unaccustomed to having his instructions questioned, angrily repeated them, but Holly refused to back down. Later, when the band was slow to respond to a summons to the rehearsal stage, Sullivan commented, "I guess the Crickets are not too excited to be on The Ed Sullivan Show." Holly, still annoyed by Sullivan's attitude, replied, "I hope they're damn more excited than I am." Sullivan retaliated by cutting them from two numbers to one, then mispronounced Holly's name during the introduction. He also saw to it that Holly's guitar amplifier's volume was barely audible, except during Buddy's guitar solo, when it was turned up. Nevertheless, the band was received so well that Sullivan was forced to invite them back; Holly responded that Sullivan did not have enough money. Archival photographs taken during the appearance show Holly smirking and ignoring a visibly angry Sullivan.[37]

During Jackie Mason's October 1964 performance on a show that had been shortened by ten minutes due to an address by President Lyndon Johnson,[38] Sullivan—on-stage but off-camera—signaled Mason that he had two minutes left by holding up two fingers.[39] Sullivan's signal distracted the studio audience, and to television viewers unaware of the circumstances, it seemed as though Mason's jokes were falling flat. Mason, in a bid to regain the audience's attention, cried, "I'm getting fingers here!" and made his own frantic hand gesture: "Here's a finger for you!" Videotapes of the incident are inconclusive as to whether Mason's upswept hand (which was just off-camera) was intended to be an indecent gesture, but Sullivan was convinced that it was, and banned Mason from future appearances on the program. Mason later insisted that he did not know what the "middle finger" meant, and that he did not make the gesture anyway.[40] In September 1965, Sullivan—who, according to Mason, was "deeply apologetic"[41]—brought Mason on the show for a "surprise grand reunion". "He said they were old pals," Nachman wrote, "news to Mason, who never got a repeat invitation."[42] Mason added that his earning power "... was cut right in half after that. I never really worked my way back until I opened on Broadway in 1986."[43]

When the Byrds performed on December 12, 1965, David Crosby got into a shouting match with the show's director. They were never asked to return.[44][45]

Sullivan decided that "Girl, we couldn't get much higher", from the Doors' signature song "Light My Fire", was too overt a reference to drug use, and directed that the lyric be changed to "Girl, we couldn't get much better" for the group's September 1967 appearance.[46] The band members "nodded their assent", according to Doors biographer Ben Fong-Torres,[47] then sang the song as written. After the broadcast, producer Bob Precht told the group, "Mr. Sullivan wanted you for six more shows, but you'll never work the Ed Sullivan Show again." Jim Morrison replied, "Hey, man, we just did the Ed Sullivan Show."[48] Sullivan, true to his word, never invited the band back but to his dismay, this was the launching pad for the psychedelic group.

The Rolling Stones famously capitulated during their fifth appearance on the show, in 1967, when Mick Jagger was told to change the titular lyric of "Let's Spend the Night Together" to "Let's spend some time together". "But Jagger prevailed," wrote Nachman, by deliberately calling attention to the censorship, rolling his eyes, mugging, and drawing out the word "t-i-i-i-me" as he sang the revised lyric. Sullivan was angered by the insubordination, but the Stones did make one additional appearance on the show, in 1969.[49][2]

Moe Howard of the Three Stooges recalled in 1975 that Sullivan had a memory problem of sorts: "Ed was a very nice man, but for a showman, quite forgetful. On our first appearance, he introduced us as the Three Ritz Brothers. He got out of it by adding, 'who look more like the Three Stooges to me'."[50] Joe DeRita, who worked with the Stooges after 1959, had commented that Sullivan had a personality "like the bottom of a bird cage."[51]

Diana Ross, who was very fond of Sullivan, later recalled Sullivan's forgetfulness during the many occasions the Supremes performed on his show. In a 1995 appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman (taped in the Ed Sullivan Theater), Ross stated, "he could never remember our names. He called us 'the girls'."[52]

In a 1990 press conference, Paul McCartney recalled meeting Sullivan again in the early 1970s. Sullivan apparently had no idea who McCartney was. McCartney tried to remind Sullivan that he was one of the Beatles, but Sullivan obviously could not remember, and nodding and smiling, simply shook McCartney's hand and left. In an interview with Howard Stern around 2012, Joan Rivers said that Sullivan had been suffering from dementia toward the end of his life.[53]

Politics[edit]

Sullivan, like many American entertainers, was pulled into the Cold War anticommunism of the late 1940s and 1950s. Tap dancer Paul Draper's scheduled January 1950 appearance on Toast of the Town met with opposition from Hester McCullough, an activist in the hunt for "subversives". Branding Draper a Communist Party "sympathizer", she demanded that Sullivan's lead sponsor, the Ford Motor Company, cancel Draper's appearance. Draper denied the charge, and appeared on the show as scheduled. Ford received over a thousand angry letters and telegrams, and Sullivan was obliged to promise Ford's advertising agency, Kenyon & Eckhardt, that he would avoid controversial guests going forward. Draper was forced to move to Europe to earn a living.[54]

After the Draper incident, Sullivan began to work closely with Theodore Kirkpatrick of the anticommunist Counterattack newsletter. He would consult Kirkpatrick if any questions came up regarding a potential guest's political leanings. Sullivan wrote in his June 21, 1950, Daily News column that "Kirkpatrick has sat in my living room on several occasions and listened attentively to performers eager to secure a certification of loyalty."[54]

Cold War repercussions manifested in a different way when Bob Dylan was booked to appear in May 1963. His chosen song was "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues", which poked fun at the ultraconservative John Birch Society and its tendency to see Communist conspiracies in many situations. No concern was voiced by anyone, including Sullivan, during rehearsals, but on the day of the broadcast, CBS's Standards and Practices department rejected the song, fearing that lyrics equating the Society's views with those of Adolf Hitler might trigger a defamation lawsuit. Dylan was offered the opportunity to perform a different song, but he responded that if he could not sing the number of his choice, he would rather not appear at all. The story generated widespread media attention in the days that followed; Sullivan denounced the network's decision in published interviews.[55]

Sullivan butted heads with Standards and Practices on other occasions, as well. In 1956, Ingrid Bergman—who had been living in "exile" in Europe since 1950 in the wake of her scandalous love affair with director Roberto Rossellini while they were both married—was planning a return to Hollywood as the star of Anastasia. Sullivan, confident that the American public would welcome her back, invited her to appear on his show and flew to Europe to film an interview with Bergman, Yul Brynner, and Helen Hayes on the Anastasia set. When he arrived back in New York, Standards and Practices informed Sullivan that under no circumstances would Bergman be permitted to appear on the show, either live or on film. Sullivan's prediction later proved correct, as Bergman won her second Academy Award for her portrayal, as well as the forgiveness of her fans.[19]

Personal life[edit]

Sullivan was engaged to champion swimmer Sybil Bauer, but she died of cancer in 1927 at the age of 23.[56] In 1926, Sullivan met and began dating Sylvia Weinstein. Weinstein tried to tell her Jewish family she was dating a man named Ed Solomon, but her brother figured out she meant Ed Sullivan. With both families strongly opposed to a Catholic–Jewish marriage, the affair was on-again-off-again for three years. They were finally married on April 28, 1930, in a City Hall ceremony, and 8 months later Sylvia gave birth to Elizabeth ("Betty"), named after Sullivan's mother, who had died that year. The Sullivans rented a suite of rooms at the Hotel Delmonico in 1944 after living at the Hotel Astor on Times Square for many years. Sullivan rented a suite next door to the family suite, which he used as an office until The Ed Sullivan Show was canceled in 1971. Sullivan was in the habit of calling his wife after every program to get her immediate critique.[57]

The Sullivans were always "on the town", eating out five nights a week at some of the trendiest clubs and restaurants, including the Stork Club, Danny's Hide-A-Way and Jimmy Kelly's. Sullivan socialized with the rich and famous, was friends with U.S. Presidents and was given audiences with various Popes.[58] In 1952, Betty Sullivan married the Ed Sullivan Show's producer, Bob Precht.[1] From the Prechts, Ed had five grandchildren—Robert Edward, Carla Elizabeth, Vincent Henry, Andrew Sullivan and Margo Elizabeth. The Sullivan and Precht families were very close; Betty died on June 7, 2014, aged 83.

Later years and death[edit]

In the fall of 1965, CBS began televising its weekly programs in color. Although the Sullivan show was seen live in the Central and Eastern time zones, it was taped for airing in the Pacific and Mountain time zones. Most of the taped programs, as well as some early kinescopes, were preserved, and excerpts have been released on home video.

By 1971, the show's ratings had plummeted. In an effort to refresh its lineup, CBS canceled the program in June 1971, along with some of its other longtime shows throughout the 1970–1971 season (later known as the rural purge). Sullivan was angered and refused to do a final show, although he remained with the network in various other capacities and hosted a 25th anniversary special in June 1973.

In early September 1974, X-rays revealed that Sullivan had an advanced growth of esophageal cancer. Doctors gave him very little time to live, and the family chose to keep the diagnosis secret from him. Sullivan, still believing his ailment to be yet another complication from a long-standing battle with gastric ulcers, died five weeks later on October 13, 1974, at New York's Lenox Hill Hospital, two weeks after his 73rd birthday.[57] His funeral was attended by 3,000 at St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York, on a cold, rainy day. Sullivan is interred in a crypt at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

Sullivan has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6101 Hollywood Blvd.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Elizabeth 'Betty' Sullivan Precht". Missoulian.com. Missoula, Montana. June 9, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b MacGuire, J. Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan. Billboard (2006), p. 222. ISBN 0823079627

- ^ "Ed Sullivan Biography | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 7662–7670.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 7670.

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time". TV Guide (December 14–20). 1996.

- ^ Block, Maxine; Rothe, Anna Herthe; Candee, Marjorie Dent (1953). Current Biography Yearbook. H. W. Wilson Company.

- ^ Michael David Harris (1968). Always on Sunday: Ed Sullivan: an Inside View. Retrieved February 10, 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ https://www.lohud.com/amp/2071105002[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nachman (2009)

- ^ "Sunday". Radio and Television Mirror. 16 (5): 41. September 1941. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ "Ed Sullivan Theater | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Big As All Outdoors" Time, October 17, 1955.

- ^ a b c "Plenty of Nothing" Time, October 13, 1967.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 7 – The All American Boy: Enter Elvis and the rock-a-billies. [Part 1]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ General Foods 25th Anniversary Show: A Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein (1954) on IMDb

- ^ Sullivan, Ed (1952). "My Story". Colliers Magazine. 1 of 3 part series (September 14, 1952).

- ^ "Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show". History1900s.about.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Merwin, Gregory (May 1957). Fifty Million People Can't Be Wrong (PDF). TV-Radio Mirror. pp. 32–33. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2012.(PDF)

- ^ "Elvis Presley | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "The Beatles | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "Online Shopping for Electronics, Apparel, Computers, Books, DVDs & more". Amazon.com. September 9, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Nachman, G. Right Here on our Stage Tonight. University of California Press (2009), Kindle location 6021. ASIN B0032UPUJ6

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 6022.

- ^ Leonard, J. (1982) A Really Big Show. Studio, p. 146. ISBN 067084246X

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle edition 6031.

- ^ Bowles, JG. A Thousand Sundays: The Story of the Ed Sullivan Show. Putnam (1980), pp. 131–2. ISBN 0399124934.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5875.

- ^ Sullivan, Ed (September 14, 1956). "My Story". Colliers Magazine. 1 of 3 part series.

- ^ Morris, Edward. "The First Families of Country Music". CMT News. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5681.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5690.

- ^ White, G.R. (1998). Bo Diddley: Living Legend. Music Sales Corp. p. 133. ISBN 1860741304.

- ^ White (1998), p. 134.

- ^ White (1998), p. 144.

- ^ Nachman (2009), p. 277.

- ^ Moore, Gary (2011). Hey Buddy: In Pursuit of Buddy Holly, My New Buddy John, and My Lost Decade of Music. Savas Beatie, p. 128. ISBN 978-1-932-71497-5.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5878.

- ^ "Vince Calandra Interview | Archive of American Television". Emmytvlegends.org. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ CBS special, The Very Best of the Ed Sullivan Show

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5940.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5950.

- ^ Nachman (2009), Kindle location 5966.

- ^ Byrds video[dead link]

- ^ "The Byrds | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. December 12, 1965. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "The Doors | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Fong-Torres, B. (2006) The Doors. Hyperion. p. 144. ISBN 140130303X

- ^ Nachman (2009), p. 373.

- ^ Nachman (2009), p. 372.

- ^ Howard, Moe. (1977, rev. 1979) Moe Howard and the Three Stooges, p. 165; Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-0723-1.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff; Howard Maurer, Joan; Lenburg, Greg; (1982). The Three Stooges Scrapbook, Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0946-5

- ^ "The Supremes | Ed Sullivan Show". Edsullivan.com. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ "March 1971…The End Of An Era: Ed Sullivan Canceled By CBS – Eyes Of A Generation…Television's Living History". Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Barnouw, E. (1990) Tube of Plenty: The Evolution of American Television. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–21. ISBN 019977059X

- ^ "Bob Dylan walks out on The Ed Sullivan Show". History.com archive. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ Sisson, Richard; Zacher, Christian K.; Cayton, Andrew R. L. (2007). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. p. 901. ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9.

- ^ a b "Ed Sullivan is Dead at 73". New York Times. October 14, 1974.

- ^ "Ed Sullivan Biography". edsullivan.com.

Cited sources[edit]

- Nachman, Gerald (2009). Right Here on our Stage Tonight! Ed Sullivan's America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520268012.

Further reading[edit]

- Leonard, John, The Ed Sullivan Age, American Heritage, May/June 1997, Volume 48, Issue 3

- Nachman, Gerald, Ed Sullivan, December 18, 2006.

- Maguire, James, Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan, Billboard Books, 2006/31/102929/

- Bowles, Jerry, A Thousand Sundays: The Story of the Ed Sullivan Show, Putnam, 1980

- Barthelme, Donald, "And Now Let's Hear It for the Ed Sullivan Show!" in Guilty Pleasures, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ed Sullivan. |

No comments:

Post a Comment