Epistle of Jude

The Epistle of Jude, often shortened to Jude, is the penultimate book of the New Testament and the Bible as a whole and is traditionally attributed to Jude, the servant of Jesus and the brother of James the Just.

Composition[edit]

The letter of Jude was one of the disputed books of the biblical canon.[1] The links between the Epistle and 2 Peter, its use of the biblical apocrypha, and its brevity raised concern. It is one of the shortest books in the Bible: only 1 chapter of 25 verses long.

Papyrus 78, containing the Epistle of Jude verses 4, 5, 7 and 8. Dated to the 3rd or 4th century.]]

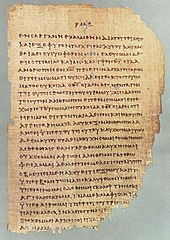

Colophon at the Epistle of Jude in the Codex Alexandrinus

Textual witnesses[edit]

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this epistle are:[2]

- Papyrus 72 (3rd/4th century)

- Papyrus 78 (3rd/4th century; extant verses 4-5, 7-8)[3]

- Codex Vaticanus (B or 03; 325-350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (א or 01; 330–360)

- Codex Alexandrinus (A or 02; 400–440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C or 04; c. 450; extant verses 3–25)[4]

Content[edit]

Jude urges his readers to defend the deposit of Christ's doctrine that had been closed by the time he wrote his epistle, and to remember the words of the apostles spoken somewhat before. Jude then asks the reader to recall how even after the Lord saved his own people out of the land of Egypt, he did not hesitate to destroy those who fell into unbelief, much as he punished the angels who fell from their original exalted status and Sodom and Gomorrah.[5] He describes in vivid terms the apostates of his day.[6] He exhorts believers to remember the words spoken by the Apostles, using language similar to the second epistle of Peter to answer concerns that the Lord seemed to tarry, How that they told you there should be mockers in the last time, who should walk after their own ungodly lusts...,[7] and to keep themselves in God's love,[8] before delivering a doxology.[9]

Jude quotes directly from the Book of Enoch, part of the scripture of the Ethiopian and Eritrean churches but rejected by other churches. He cites Enoch's prophecy that the Lord would come with many thousands of his saints to render judgment on the whole world. He also paraphrases (verse 9) an incident in a text that has been lost about Satan and Michael the Archangel quarreling over the body of Moses.

Outline[edit]

I. Salutation (1–3)

II. Occasion for the Letter (3–4)

A. The change of Subject (3)

B. The Reason for the Change: The Presence of Godless Apostates (4)

III. Warning against the False Teachers (5–16)

A. Historical Examples of the Judgement of Apostates (5–7)

1. Unbelieving Israel (5)

2. Angels who fell (6)

3. Sodom and Gomorrah (7)

B. Description of the Apostates of Jude's Day (8–16)

1. Their slanderous speech deplored (8–10)

2. Their character graphically portrayed (11–13)

3. Their destruction prophesied (14–16)

IV. Exhortation to Believers (17–23)

V. Concluding Doxology (24–25)[10]

Canonical status[edit]

The Epistle of Jude is held as canonical in the Christian Church. Conservative scholars date it between 70 and 90. Some scholars consider the letter a pseudonymous work written between the end of the 1st century and the first quarter of the 2nd century because of its references to the apostles[11] and to tradition[12] and because of its competent Greek style.[13][14][15]

"More remarkable is the evidence that by the end of the second century Jude was widely accepted as canonical."[16] Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and the Muratorian canon considered the letter canonical. The first historical record of doubts as to authorship are found in the writings of Origen of Alexandria, who spoke of the doubts held by some, albeit not him. Eusebius classified it with the "disputed writings, the antilegomena." The letter was eventually accepted as part of the Canon by Church Fathers such as Athanasius of Alexandria[17] and the Synods of Laodicea (c. 363)[18] and Carthage (c. 397).[19]

Authorship[edit]

The epistle title is written as follows: "Jude, a servant of Jesus Christ and brother of James" (NRSV). "James" is generally taken to mean James the Just, a prominent leader in the early church. Not a lot is known of Jude, which would explain the apparent need to identify him by reference to his better-known brother.[13]

As the brother of James the Just, it has traditionally meant Jude was also the brother of Jesus, since James is described as being the brother of Jesus. For instance Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 AD) wrote in his work "Comments on the Epistle of Jude" that Jude, the Epistle of Jude's author, was a son of Joseph and a brother of Jesus (without specifying whether he was a son of Joseph by a previous marriage or of Joseph and Mary).[20]

There is also a dispute as to whether "brother" means someone who has the same father and mother, or a half-brother or cousin or more distant familial relationship. This dispute over the true meaning of "brother" grew as the doctrine of the Virgin Birth evolved.[21][22][23]

Outside the book of Jude, a "Jude" is mentioned five times in the New Testament: three times as Jude the Apostle (Luke 6:16, Acts 1:13, John 14:22), and twice as Jude the brother of Jesus (Matthew 13:55, Mark 6:3) (aside from references to Judas Iscariot and Judah (son of Jacob)). Debate continues as to whether the author of the epistle is either, both, or neither. Some scholars have argued that since the author of the letter has not identified himself as an apostle and actually refers to the apostles as a third party, he cannot be identified with Jude the Apostle. Others have drawn the opposite conclusion, i.e., that, as an apostle, he would not have made a claim of apostleship on his own behalf.[24]

Style[edit]

The Epistle of Jude is a brief book of only a single chapter with 25 verses. It was composed as an encyclical letter—that is, one not directed to the members of one church in particular, but intended rather to be circulated and read in all churches.

The wording and syntax of this epistle in its original Greek demonstrates that the author was capable and fluent. The epistle is addressed to Christians in general,[25] and it warns them about the doctrine of certain errant teachers to whom they were exposed. The epistle's style is combative, impassioned, and rushed. Many examples of evildoers and warnings about their fates are given in rapid succession.

The epistle concludes with a doxology, which is considered by Peter H. Davids to be one of the highest in quality contained in the Bible.[26]

Jude and 2 Peter[edit]

Part of Jude is very similar to 2 Peter (mainly 2 Peter chapter 2), so much so that most scholars agree that there is a dependence between the two, i.e., that either one letter used the other directly, or they both drew on a common source.[27] Comparing the Greek text portions of 2 Peter 2:1–3:3 (426 words) to Jude 4–18 (311 words) results in 80 words in common and 7 words of substituted synonyms.[28]

The shared passages are:[29]

| 2 Peter | Jude |

|---|---|

| 1:5 | 3 |

| 1:12 | 5 |

| 2:1 | 4 |

| 2:4 | 6 |

| 2:6 | 7 |

| 2:10–11 | 8–9 |

| 2:12 | 10 |

| 2:13–17 | 11–13 |

| 3:2-3 | 17-18 |

| 3:14 | 24 |

| 3:18 | 25 |

Because this epistle is much shorter than 2 Peter, and due to various stylistic details, some writers consider Jude the source for the similar passages of 2 Peter.[30] However, other writers, arguing that Jude 18 quotes 2 Peter 3:3 as past tense, consider Jude to have come after 2 Peter.[31]

Some scholars who consider Jude to predate 2 Peter note that the latter appears to quote the former but omits the reference to the non-canonical book of Enoch.[32]

References to other books[edit]

The Epistle of Jude references at least three other books, with two (Book of Zechariah & 2 Peter) being canonical in all churches and the other (Book of Enoch) non-canonical in most churches.

Verse 9 refers to a dispute between Michael the Archangel and the devil about the body of Moses. Some interpreters understand this reference to be an allusion to the events described in Zechariah 3:1–2.[33][34] The classical theologian Origen attributes this reference to the non-canonical Assumption of Moses.[35] According to James Charlesworth, there is no evidence the surviving book of this name ever contained any such content.[36] Others believe it to be in the lost ending of the book.[36][37]

Verses 14–15 contain a direct quotation of a prophecy from 1 Enoch 1:9. The title "Enoch, the seventh from Adam" is also sourced from 1 En. 60:1. Most commentators assume that this indicates that Jude accepts the antediluvian patriarch Enoch as the author of the Book of Enoch which contains the same quotation. However, an alternative explanation is that Jude quotes the Book of Enoch aware that verses 14–15 are in fact an expansion of the words of Moses from Deuteronomy 33:2.[38][39][40] This is supported by Jude's unusual Greek statement that "Enoch the Seventh from Adam prophesied to the false teachers", not concerning them.[41]

The Book of Enoch is not considered canonical by most churches, although it is by the Ethiopian Orthodox church. According to Western scholars, the older sections of the Book of Enoch (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) date from about 300 BC and the latest part (Book of Parables) probably was composed at the end of the 1st century BC.[42] 1 Enoch 1:9, mentioned above, is part of the pseudepigrapha and is among the Dead Sea Scrolls [4Q Enoch (4Q204[4QENAR]) COL I 16–18].[43] It is generally accepted by scholars that the author of the Epistle of Jude was familiar with the Book of Enoch and was influenced by it in thought and diction.[44]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 2 23

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- ^ Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland (eds), Novum Testamentum Graece, 26th edition, (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1991), p. 689.

- ^ Jude 5–7

- ^ Jude 8–16

- ^ Jude 18

- ^ Jude 21

- ^ Jude 24–25

- ^ NIV Bible (Large Print ed.). (2007). London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

- ^ Jude 17–18

- ^ Jude 3

- ^ a b "scripture".

- ^ Norman Perrin, (1974) The New Testament: An Introduction, p. 260

- ^ Bauckham, RJ (1986), Word Biblical Commentary, Vol.50, Word (UK) Ltd. p.16

- ^ Bauckham, RJ (1986), Word Biblical Commentary, Vol.50, Word (UK) Ltd. p.17

- ^ Lindberg, Carter (2006). A Brief History of Christianity. Blackwell Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 1-4051-1078-3

- ^ Council of Laodicea at bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ B. F. Westcott, A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament (5th ed. Edinburgh, 1881), pp. 440, 541–2.

- ^ "Jude wrote the Catholic Epistle, the brother of the sons of Joseph, and very religious, while knowing the near relationship of the Lord, yet did not say that he himself was His brother. But what said he? "Jude, a servant of Jesus Christ,"—of Him as Lord; but "the brother of James." For this is true; he was His brother, (the son) of Joseph."of Alexandria, Clement. Comments on the Epistle of Jude. newadvent.org. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Jocelyn Rhys, Shaken Creeds: The Virgin Birth Doctrine: A Study of Its Origin, Kessinger Publishing (reprint), 2003 [1922] ISBN 0-7661-7988-5, pp 3–53

- ^ Chester, A and Martin, RP (1994), 'The Theology of the Letters of James, Peter and Jude', CUP, p.65

- ^ Bauckham, R. J. (1986), Word Biblical Commentary, Vol.50, Word (UK) Ltd. p.14

- ^ Bauckham, R. J. (1986), Word Biblical Commentary, Vol.50, Word (UK) Ltd. p.14f

- ^ Jude 1:1

- ^ Davids, Peter H. (2006). The Pillar New Testament Commentary: The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eardmans Publishing Co. p. 106.

- ^ Introduction to 2 Peter in Expositor's Bible Commentary, Ed. F. E. Gaebelein, Zondervan 1976–1992

- ^ Callan 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 10.

- ^ e.g. Callan 2004, pp. 42–64.

- ^ e.g. John MacArthur 1, 2, 3, John Jude 2007 p101 "...closely parallels that of 2 Peter (2:1–3:4), and it is believed that Peter's writing predated Jude for several reasons: (1) Second Peter anticipates the coming of false teachers (2 Peter 2:1–2; 3:3), whereas Jude deals with their arrival (verses 4, 11–12, 17–18); and (2) Jude quotes directly from 2 Peter 3:3 and acknowledges that it is from an apostle (verses 17–18)."

- ^ Dale Martin 2009 (lecture). "24. Apocalyptic and Accommodation". Yale University. Accessed July 22, 2013.

- ^ Peter H. Davids; Douglas J. Moo; Robert Yarbrough (5 April 2016). 1 and 2 Peter, Jude, 1, 2, and 3 John. Zondervan. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-310-53025-1.

- ^ R. C. Lucas; Christopher Green (2 May 2014). The Message of 2 Peter & Jude. InterVarsity Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-0-8308-9784-1.

- ^ "ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second".

- ^ a b James Charlesworth Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, p. 76, Google books link

- ^ The Assumption of Moses: a critical edition with commentary By Johannes Tromp. P270

- ^ Charles R. Enoch OUP, p. 119

- ^ Nickelsburg G. 1 Enoch Fortress

- ^ Cox S. Slandering celestial beings

- ^ AUTOI dative

- ^ Fahlbusch E., Bromiley G. W. The Encyclopedia of Christianity: P-Sh page 411, ISBN 0-8028-2416-1 (2004)

- ^ Clontz, T. E. and J., The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh, Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p.711, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ "Apocalyptic Literature" (column 220), Encyclopedia Biblica

Sources[edit]

- Callan, Terrance (2004). "Use of the Letter of Jude by the Second Letter of Peter". Biblica. 85: 42–64.

- Robinson, Alexandra (2017). Jude on the Attack: A Comparative Analysis of the Epistle of Jude, Jewish Judgement Oracles, and Greco-Roman Invective. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567678799.

Further reading[edit]

- Vela, Tyler (2017). "Canonical Exclusion or Embrace? The Use of Enoch in the Epistle of Jude". Academia.edu.

- Bacon, Benjamin Wisner (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 536–538.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Epistle of Jude |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Online translations of the Epistle of Jude:

- Jude in New American Bible

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- Jude at Bible Gateway (various versions)

- Early Christian writings: Epistle of Jude: comparable translations and interpretations

Audiobook Version:

Additional information:

Epistle of Jude | ||

| Preceded by Third John | New Testament Books of the Bible | Succeeded by Revelation |

No comments:

Post a Comment