Luddite

The Luddites were a secret oath-based organization[1] of English textile workers in the 19th century, a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery as a form of protest. The group was protesting against manufacturers who used machines in what they called "a fraudulent and deceitful manner" to get around standard labour practices.[2] Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste, as machines would replace their role in the industry.[3] Many Luddites were owners of workshops that had closed because factories could sell the same products for less. But when workshop owners set out to find a job at a factory, it was very hard to find one because producing things in factories required fewer workers than producing those same things in a workshop. This left many people unemployed and angry.[4] Over time, the term has come to mean one opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation, or new technologies in general.[5] The Luddite movement began in Nottingham in England and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816.[6] Mill and factory owners took to shooting protesters and eventually the movement was suppressed with legal and military force.

Etymology[edit]

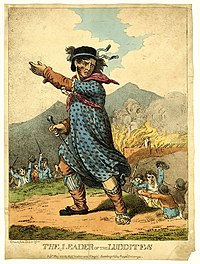

The name Luddite (/ˈlʌd.aɪt/) is of uncertain origin. The movement was said to be named after Ned Ludd, an apprentice who allegedly smashed two stocking frames in 1779 and whose name had become emblematic of machine destroyers. Ned Ludd, however, was completely fictional and used as a way to shock and provoke the government.[7][8][9] The name developed into the imaginary General Ludd or King Ludd, who was reputed to live in Sherwood Forest like Robin Hood.[10][a]

Historical precedents[edit]

The lower classes of the 18th century were not openly disloyal to the king or government, generally speaking,[13] and violent action was rare because punishments were harsh. The majority of individuals were primarily concerned with meeting their own daily needs.[14] Working conditions were harsh in the English textile mills at the time but efficient enough to threaten the livelihoods of skilled artisans.[15] The new inventions produced textiles faster and cheaper because they were operated by less-skilled, low-wage labourers, and the Luddite goal was to gain a better bargaining position with their employers.[16]

Kevin Binfield asserts that organized action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and he suggests that the movements of the early 19th century should be viewed in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars, rather than as an absolute aversion to machinery.[17][18][19] Irregular rises in food prices provoked the Keelmen to riot in the port of Tyne in 1710[20] and tin miners to steal from granaries at Falmouth in 1727. There was a rebellion in Northumberland and Durham in 1740, and an assault on Quaker corn dealers in 1756. Skilled artisans in the cloth, building, shipbuilding, printing, and cutlery trades organized friendly societies to peacefully insure themselves against unemployment, sickness, and intrusion of foreign labour into their trades, as was common among guilds.[21][b]

Malcolm L. Thomis argued in his 1970 history The Luddites that machine-breaking was one of a very few tactics that workers could use to increase pressure on employers, to undermine lower-paid competing workers, and to create solidarity among workers. "These attacks on machines did not imply any necessary hostility to machinery as such; machinery was just a conveniently exposed target against which an attack could be made."[19] An agricultural variant of Luddism occurred during the widespread Swing Riots of 1830 in southern and eastern England, centering on breaking threshing machines.[22]

Birth of the movement[edit]

- See also Barthélemy Thimonnier, whose sewing machines were destroyed by tailors who believed that their jobs were threatened

Handloom weavers burned mills and pieces of factory machinery. Textile workers destroyed industrial equipment during the late 18th century,[2] prompting acts such as the Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1788.

The Luddite movement emerged during the harsh economic climate of the Napoleonic Wars, which saw a rise of difficult working conditions in the new textile factories. Luddites objected primarily to the rising popularity of automated textile equipment, threatening the jobs and livelihoods of skilled workers as this technology allowed them to be replaced by cheaper and less skilled workers.[2] The movement began in Arnold, Nottingham on 11 March 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England over the following two years.[23][2] The British economy suffered greatly in 1810 to 1812, especially in terms of high unemployment and inflation. The causes included the high cost of the wars with Napoleon, Napoleon's Continental System of economic warfare, and escalating conflict with the United States. The crisis led to widespread protest and violence, but the middle classes and upper classes strongly supported the government, which used the army to suppressed all working class unrest, especially the Luddite movement.[24][25]

The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding industrial towns to practice military-like drills and manoeuvres. Their main areas of operation began in Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812 then Lancashire by March 1813. They smashed stocking frames and cropping frames among others. There does not seem to have been any political motivation behind the Luddite riots and there was no national organization; the men were merely attacking what they saw as the reason for the decline in their livelihoods.[26] Luddites battled the British Army at Burton's Mill in Middleton and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire.[27] The Luddites and their supporters anonymously sent death threats to, and possibly attacked, magistrates and food merchants. Activists smashed Heathcote's lacemaking machine in Loughborough in 1816.[28] He and other industrialists had secret chambers constructed in their buildings that could be used as hiding places during an attack.[29]

In 1817, an unemployed Nottingham stockinger and probably ex-Luddite, named Jeremiah Brandreth led the Pentrich Rising. While this was a general uprising unrelated to machinery, it can be viewed as the last major heroic Luddite act.[30]

Government response[edit]

The British Army clashed with the Luddites on several occasions. At one time there were more British soldiers fighting the Luddites than there were fighting Napoleon on the Iberian Peninsula.[31][d] Four Luddites, led by George Mellor, ambushed and assassinated mill owner William Horsfall of Ottiwells Mill in Marsden, West Yorkshire at Crosland Moor in Huddersfield. Horsfall had remarked that he would "Ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood".[32] Mellor fired the fatal shot to Horsfall's groin, and all Four men were arrested. One of the men, Benjamin Walker, turned informant, and the other three were hanged.[33][34][35]

Lord Byron denounced what he considered to be the plight of the working class, the government's inane policies and ruthless repression in the House of Lords on 27 February 1812: "I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country".[36]

The British government sought to suppress the Luddite movement with a mass trial at York in January 1813, following the attack on Cartwrights mill at Rawfolds near Cleckheaton. The government charged over 60 men, including Mellor and his companions, with various crimes in connection with Luddite activities. While some of those charged were actual Luddites, many had no connection to the movement. Although the proceedings were legitimate jury trials, many were abandoned due to lack of evidence and 30 men were acquitted. These trials were certainly intended to act as show trials to deter other Luddites from continuing their activities. The harsh sentences of those found guilty, which included execution and penal transportation, quickly ended the movement.[37][38] Parliament made "machine breaking" (i.e. industrial sabotage) a capital crime with the Frame Breaking Act of 1812.[39] Lord Byron opposed this legislation, becoming one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites after the treatment of the defendants at the York trials.[40]

Legacy[edit]

In the 19th century, occupations that arose from the growth of trade and shipping in ports, also in "domestic" manufacturers, were notorious for precarious employment prospects. Underemployment was chronic during this period,[21] and it was common practice to retain a larger workforce than was typically necessary for insurance against labour shortages in boom times.[21]

Moreover, the organization of manufacture by merchant-capitalists in the textile industry was inherently unstable. While the financiers' capital was still largely invested in raw material, it was easy to increase commitment where trade was good and almost as easy to cut back when times were bad. Merchant-capitalists lacked the incentive of later factory owners, whose capital was invested in building and plants, to maintain a steady rate of production and return on fixed capital. The combination of seasonal variations in wage rates and violent short-term fluctuations springing from harvests and war produced periodic outbreaks of violence.[21]

Modern usage[edit]

Nowadays, the term is often used to describe someone that is opposed or resistant to new technologies.[41]

In 1956, during a British Parliamentary debate, a Labour spokesman said that "organised workers were by no means wedded to a 'Luddite Philosophy'."[42] More recently, the term Neo-Luddism has emerged to describe opposition to many forms of technology.[43] According to a manifesto drawn up by the Second Luddite Congress (April 1996; Barnesville, Ohio), Neo-Luddism is "a leaderless movement of passive resistance to consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age."[44]

The term "Luddite fallacy" is used by economists in reference to the fear that technological unemployment inevitably generates structural unemployment and is consequently macroeconomically injurious. If a technological innovation results in a reduction of necessary labour inputs in a given sector, then the industry-wide cost of production falls, which lowers the competitive price and increases the equilibrium supply point which, theoretically, will require an increase in aggregate labour inputs.[45]

See also[edit]

- Development criticism

- Simple living

- Technophobia

- Turner Controversy – return to pre-industrial methods of production

- Ruddington Framework Knitters' Museum – features a Luddite gallery

Notes[edit]

- ^ Historian Eric Hobsbawm has called their machine wrecking "collective bargaining by riot", which had been a tactic used in Britain since the Restoration because manufactories were scattered throughout the country, and that made it impractical to hold large-scale strikes.[11][12]

- ^ The Falmouth magistrates reported to the Duke of Newcastle (16 Nov. 1727) that "the unruly tinners" had "broke open and plundered several cellars and granaries of corn." Their report concludes with a comment which suggests that they were not able to understand the rationale of the direct action of the tinners: "the occasion of these outrages was pretended by the rioters to be a scarcity of corn in the county, but this suggestion is probably false, as most of those who carried off the corn gave it away or sold it at quarter price." PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ The Penny Magazine 1844, p.33

- ^ Hobsbawm has popularized this comparison and refers to the original statement in Frank Ongley Darvall (1934) Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England, London, Oxford University Press, p. 260.

References[edit]

- ^ Byrne, Richard (August 2013). "A Nod to Ned Ludd". The Baffler. 23 (23): 120–128. doi:10.1162/BFLR_a_00183. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d Conniff, Richard (March 2011). "What the Luddites Really Fought Against". Smithsonian. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Who were the Luddites?". History.com. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ https://economixcomix.com/

- ^ "Luddite". Compact Oxford English Dictionary at AskOxford.com. Accessed 22 February 2010.

- ^ Linton, David (Fall 1992). "THE LUDDITES: How Did They Get That Bad Reputation?". Labor History. 33 (4): 529–537. doi:10.1080/00236569200890281. ISSN 0023-656X.

- ^ Anstey at Welcome to Leicester (visitoruk.com) According to this source, "A half-witted Anstey lad, Ned Ludlam or Ned Ludd, gave his name to the Luddites, who in the 1800s followed his earlier example by expressing violence against machinery in protest against the Industrial Revolution." It is a known theory that Ned Ludd was the group leader of the Luddites.

- ^ Palmer, Roy, 1998, The Sound of History: Songs and Social Comment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-215890-1, p. 103

- ^ Chambers, Robert (2004), Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, Part 1, Kessinger, ISBN 978-0-7661-8338-4, p. 357

- ^ "The National Archives Learning Curve | Power, Politics and Protest | the Luddites". The National Archives. Retrieved 19 August 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 59.

- ^ Autor, D. H.; Levy, F.; Murnane, R. J. (1 November 2003). "The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (4): 1279–1333. doi:10.1162/003355303322552801. hdl:1721.1/64306. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010.

- ^ Robert Featherstone Wearmouth (1945). Methodism and the common people of the eighteenth century. Epworth Press. p. 51. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ R. F. Wearmouth, Methodism and the Common People of the Eighteenth Century. (1945), esp. chs. 1 and 2.

- ^ Clancy, Brett (October 2017). "Rebel or Rioter? Luddites Then and Now". Society. 54 (5): 392–398. doi:10.1007/s12115-017-0161-6. ISSN 0147-2011. S2CID 148899583.

- ^ Merchant, Brian (2 September 2014). "You've Got Luddites All Wrong". Vice. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Binfield, Kevin (2004). Luddites and Luddism. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Rude, George (2001). The Crowd in History: A Study of Popular Disturbances in France and England, 1730–1848. Serif.

- ^ a b Thomis, Malcolm (1970). The Luddites: Machine Breaking in Regency England. Shocken.

- ^ "Historical events – 1685–1782 | Historical Account of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (pp. 47–65)". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Charles Wilson, England's Apprenticeship, 1603-1763 (1965), pp. 344–45. PRO, SP 36/4/22.

- ^ Harrison, J. F. C. (1984). The Common People: A History from the Norman Conquest to the Present. London, Totowa, N.J: Croom Helm. pp. 249–53. ISBN 0709901259. OL 16568504M.

- ^ Beckett, John. "Luddites". The Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway. Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon (2013), pp 410–412.

- ^ Francois Crouzet, Britain Ascendant (1990) pp 277–279.

- ^ "The Luddites 1811-1816". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Dinwiddy, J.R. (1992). "Luddism and Politics in the Northern Counties". Radicalism and Reform in Britain, 1780–1850. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 371–401. ISBN 9781852850623.

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 188.

- ^ "Workmen discover secret chambers". BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Summer D. Leibensperger, "Brandreth, Jeremiah (1790–1817) and the Pentrich Rising." The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (2009): 1-2.

- ^ Hobsbawm 1952, p. 58: "The 12,000 troops deployed against the Luddites greatly exceeded in size the army which Wellington took into the Peninsula in 1808."

- ^ Sharp, Alan (4 May 2015). Grim Almanac of York. The History Press. ISBN 9780750964562.

- ^ Murder of William Horsfall - Newspaper report on the murder of William Horsfall

- ^ Huddersfield Exposed - William Horsfall (1770-1812).

- ^ "8th January 1813: The execution of George Mellor, William Thorpe & Thomas Smith". The Luddite Bicentenary - 1811-1817. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2020 – via ludditebicentenary.blogspot.com.

- ^ Lord Byron, Debate on the 1812 Framework Bill, Hansard, http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1812/feb/27/frame-work-bill#S1V0021P0_18120227_HOL_7

- ^ "Luddites in Marsden: Trials at York". Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Elizabeth Gaskell: The Life of Charlotte Bronte, Vol. 1, Ch. 6, for contemporaneous description of attack on Cartwright.

- ^ "Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812" at books.google.com

- ^ "Lord Byron and the Luddites | The Socialist Party of Great Britain". www.worldsocialism.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ https://www.dictionary.com/browse/luddite

- ^ Sale 1995, p. 205.

- ^ Jones 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1 February 1997). "America's New Luddites". Le Monde diplomatique. Archived from the original on 30 June 2002.

- ^ Jerome, Harry (1934). Mechanization in Industry, National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 32–35.

Further reading[edit]

- Archer, John E. (2000). "Chapter 4: Industrial Protest". Social unrest and popular protest in England, 1780–1840. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57656-7.

- Bailey, Brian J (1998). The Luddite Rebellion. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-1335-1.

- Binfield, Kevin (2004). Writings of the Luddites. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-7612-5.

- Fox, Nicols (2003). Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-860-5.

- Grint, Keith & Woolgar, Steve (1997). "The Luddites: Diablo ex Machina". The machine at work: technology, work, and organization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-7456-0924-9.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (1952). "The Machine Breakers". Past & Present. 1 (1): 57–70. doi:10.1093/past/1.1.57.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Steven E. (2006). Against technology: from the Luddites to Neo-Luddism. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-97868-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGaughey, Ewan (2018). "Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy". ssrn.com. SSRN 3044448.

- Pynchon, Thomas (28 October 1984). "Is It O.k. to Be a Luddite?". The New York Times.

- Randall, Adrian (2002). Before the Luddites: Custom, Community and Machinery in the English Woollen Industry, 1776–1809. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89334-3.

- Rude, George (2005). "Chapter 5, Luddism". The crowd in History, 1730–1848. Serif. ISBN 978-1-897959-47-3.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (1995). Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age. Basic Books. ISBN 0-201-40718-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, E. P. (1991). The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013603-6. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Luddite |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Luddism. |

| Look up Luddite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Luddite Bicentenary - Comprehensive chronicle of the Luddite uprisings

- The Luddite Link - Comprehensive historical resources for the original West Yorkshire Luddites, University of Huddersfield.

- Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education

- The Luddites and the Combination Acts from the Marxists Internet Archive

- The Luddites (1988) Thames Television drama-documentary about the West Riding Luddites.

- 4 April 2020, BBC, Mast fire probe amid 5G coronavirus claims, bbc.com

No comments:

Post a Comment