Emil Theodor Kocher

Emil Theodor Kocher | |

|---|---|

Emil Theodor Kocher | |

| Born | 25 August 1841 |

| Died | 27 July 1917 (aged 75) |

| Known for | Developer of Thyroid surgery |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Surgeon |

| Institutions | University of Bern |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1909) |

Emil Theodor Kocher (25 August 1841 – 27 July 1917) was a Swiss physician and medical researcher who received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid.[1][2] Among his many accomplishments are the introduction and promotion of aseptic surgery and scientific methods in surgery, specifically reducing the mortality of thyroidectomies below 1% in his operations.

He was the first Swiss citizen and first surgeon to ever receive a Nobel Prize. He was considered a pioneer and leader in the field of surgery in his time.[3]

Early life and personal life[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Kocher's father was Jakob Alexander Kocher (1814–1893), the sixth of seven children to Samuel Kocher (1771–1842), a carpenter, and Barbara Sutter (1772–1849).[4][5] Jakob Alexander Kocher was a railway engineer and he moved in 1845 to Burgdorf, Switzerland (near Bern), because of his job as regional engineer of Emmental (Bezirksingenieur).[5] He was named chief engineer for street and water in the canton of Bern at the age of 34 years and he moved with his family to the capital, the city of Bern.[5] In 1858 he left the states service and managed several engineering projects around Bern.[5]

Theodor Kocher's mother was Maria Kocher (née Wermuth) living from 1820 to 1900.[2][5] She was a very religious woman and part of the Moravian Church; together with Jakob Alexander, she raised a family of five sons and one daughter (Theodor Kocher was the second son).

Theodor Kocher was born on 25 August 1841 in Bern and baptized in the local Bern Minster on 16 September 1841.[5] Together with the family, he moved to Burgdorf in 1845 where he started school. Later his family moved back to Bern where he went to middle and high school (Realschule and Literaturgymnasium) where he was the first of his class.[5] During high school, Theodor was interested in many subjects and was specifically drawn to art and classical philology but finally decided to become a doctor.[6]

Studies[edit]

He started his studies after obtaining the Swiss Matura in 1858 at the University of Bern where Anton Biermer and Hermann Askan Demme were teaching, two professors that impressed him most.[5] He was a studious and dedicated student but still became a member of the Schweizerischer Zofingerverein, a Swiss fraternity. He obtained his doctorate in Bern in 1865[7][8] (March 1865)[5] or 1866[2] [note 1] with his dissertation about Behandlung der croupösen Pneumonie mit Veratrum-Präparaten (literal English translation: The treatment of croupous pneumonia with Veratrum preparations.) under professor Biermer with the predicate summa cum laude unamimiter.[5]

In spring 1865, Kocher followed his teacher Biermer to Zürich, where Theodor Billroth was director of the hospital and influenced Kocher significantly.[7] Kocher then proceeded to start a journey through Europe to meet several of the most famous surgeons of the time.[5] It is not clear how Kocher financed his trip but according to Bonjour (1981) he received money from an unknown female Suisse romande philanthropist who also supported his friend Marc Dufour and was probably a member of the Moravian Church.[5] In October 1865, he traveled to Berlin, passing through Leipzig and visiting an old friend from high school, Hans Blum. In Berlin, he studied under Bernhard von Langenbeck and applied for an assistant position with Langenbeck and Rudolf Virchow. Since there was no position available, in April 1867 Kocher moved on to London where he first met Jonathan Hutchinson and then worked for Henry Thompson and John Erichsen. Furthermore, he was interested in the work of Isaac Baker Brown and Thomas Spencer Wells, who also invited Kocher to go to the opera with his family. In July 1867, he traveled on to Paris to meet Auguste Nélaton, Auguste Verneuil and Louis Pasteur. During his travels, he did not only learn novel techniques but also got to know leading surgeons in person and learned to speak English fluently which allowed him later on to follow the scientific progress in the English speaking world with ease.[5]

Once returned to Bern, Kocher prepared for his habilitation and on 12 October 1867, he wrote a petition to the ministry of education to award him the venia docendi (Latin: to instruct) which was granted to him.[5] He became assistant to Georg Lücke who left Bern in 1872 to become professor in Strasbourg.[note 2] Kocher was hoping to get his position, but at the time it was customary to appoint German professors to positions at Swiss universities. Accordingly, the faculty suggested Franz König before Kocher to follow Lücke. However, the students and assistants as well as many doctors preferred Kocher and started a petition to the Bernese government to choose Kocher. Also the press was in favor of Kocher and several famous foreign surgeons, such as Langenbeck from Berlin and Billroth from Vienna, wrote letters in support of Kocher. Under this public pressure, the Bernese government (Regierungsrat) chose Kocher as the successor of Lücke as Ordinary Professor of Surgery and Director of the University Surgical Clinic at the Inselspital on 16 March 1872, despite a different proposal by the faculty.[5]

Personal life[edit]

In 1869, he married Marie Witschi-Courant[9][note 3] (1841–1921)[7][8] or (1850[5]–1925).[note 4] She was the daughter of Johannes Witschi, who was a merchant,[2] and she had three sons together with Kocher. The Kochers first lived at the Marktgasse in Bern and moved in 1875 to a bigger house in the Villette. The house became a place for friends, colleagues and guests to gather and many patients from Kocher's clinic were invited to dine at the Villette.[5]

Like his mother, Kocher was a deeply religious man and also part of the Moravian Church. This was an uncommon trait that not many colleagues and co-workers shared and until his death, Kocher attributed all his successes and failures to God. He thought that the rise of materialism (especially in science) was a great evil, and he attributed the outbreak of the First World War.[5]

Kocher was involved in the education of his three sons and played tennis with them and went horseback riding with them.[5] The eldest son Albert (1872–1941)[8] would follow him to the surgical clinic in Bern and become Assistant Professor of Surgery.[10]

On the evening of 23 July 1917, he was called into the Inselspital for an emergency. Kocher executed the surgery but afterwards felt unwell and went to bed, working on scientific notes. He then fell unconscious and died on 27 July 1917.[5]

Career[edit]

The call for an ordinary professorship at the University of Bern at the age of 30 was the first big career step for Theodor Kocher. In the 45 years he served as professor at the university, he oversaw the re-building of the famous Bernese Inselspital, published 249 scholarly articles and books, trained numerous medical doctors and treated thousands of patients. He made major contributions to the fields of applied surgery, neurosurgery and, especially, thyroid surgery and endocrinology. For his work he received, among other honors, the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. According to Asher, the field of surgery has transformed radically during the time of Theodore Kocher and later generations will build on the foundations created by Kocher – if a future historian wanted to describe the state of surgery at the beginning of the 20th century, he only need mention Kocher's Text-Book of Operative Surgery.[5]

Three main factors contributed to Kocher's success as a surgeon, according to Bonjour (1981). The first factor was his consequent implementation of antiseptic wound treatment which prevented infection and later death of the patients. The second factor, according to Erich Hintzsche, was his monitoring of the anesthesia where he used special masks and later used local anesthesia for goitre surgery which decreased or removed the dangers of anesthesia. As a third factor, Hintzsche mentions the minimal blood loss which Kocher achieved. Even the smallest source of blood during surgery was precisely controlled and inhibited by Kocher, initially because he thought that decomposing blood would constitute an infection risk for the patient.[5]

Early career[edit]

Kocher first attained international recognition with his method to reset a dislocated shoulder published in 1870.[2][11] The new procedure was much less painful and safer than the traditionally used procedure and could be performed by a single physician. Kocher developed the procedure through his knowledge of anatomy.[5] In the same period, Kocher also studied the phenomena of bullet wounds and how they can cause bone fractures. From these studies resulted one public lecture in 1874 Die Verbesserung der Geschosse vom Standpunkt der Humanitaet (English: The improvement of the bullets from the standpoint of humanity.) and an 1875 manuscript Ueber die Sprengwirkung der modernen Kriegsgewehrgeschosse (English: Over the explosive effect of modern war rifle bullets.) He showed that small caliber bullets were less harmful and recommended to use bullets with slower speed.[5]

Relocation of Inselspital and call to Prague[edit]

As soon as Kocher became professor, he wanted to modernize the practices at the Bernese Inselspital. He noticed that the old building did not suffice the modern standards and was too small – half of the patients seeking medical attention had to be turned away.[5] In spring 1878, he visited several institutions around Europe to evaluate novel innovations for hospitals and implement them if possible in Bern. He wrote down his observations in a lengthy report for the Bernese government, giving instructions even for architectonic details. In a speech on 15 November 1878, he informed the general public about the pressing needs of a new hospital building. Finally, he used his call to Prague to pressure the government: He would only stay in Bern if he was either granted 75 beds in the new building or would get money to increase his facilities in the old building. Finally, in the winter of 1884/1885 the new building was finished and the Inselspital could be moved.[5]

At the time, Prague had the third largest university clinic in the German speaking world and it was a great honor for Kocher when he received a call as a professor to Prague in spring 1880. Many colleagues, especially international ones, urged Kocher to accept while Bernese doctors and colleagues begged him to stay.[5] Kocher used this call, to demand certain improvements for the university clinic from the Bernese government. They accepted all his demands, the government promised him to begin building the new Inselspital building the next year, increased his credit for surgical equipment and books to 1000 franks and increased the number of beds for Kocher in the new Inselspital. Thus, Kocher decided to stay and many Bernese and Swiss students and professionals thanked him for it. He cited the affection of his students as one of his main reasons for staying. The university students organized a torchlight procession on 8 June 1880 in his honor.[5]

Aseptic surgery[edit]

It is unclear whether Kocher directly knew Joseph Lister, who pioneered the antiseptic (using chemical means to kill bacteria) method, but Kocher was in correspondence with him.[5] Kocher had recognized the importance of aseptic techniques early on, introducing them to his peers at a time when this was considered revolutionary. In a hospital report from 1868, he attributed the lower mortality directly to the "antiseptic Lister's wound bandaging method" and he could later as director of the clinic order strict adherence to the antiseptic method.[5] Bonjour (1981) describes how his assistants were worried about wound infection for fear of having to explain their failure to Kocher himself.[5] Kocher made it a matter of principle to investigate the cause of every wound infection and remove every potential source of infection, he also banned visitors from his surgeries for this reason.[5]

He published multiple works on aseptic treatment and surgery.[7]

Contributions to Neurosurgery[edit]

Kocher also contributed significantly to the field of neurology and neurosurgery. In this area, his research was pioneering and covered the areas of concussion, neurosurgery and intracranial pressure (ICP).[5] Furthermore, he investigated the surgical treatment of epilepsy and spinal and cranial trauma. He found that in some cases, the epilepsy patients had a brain tumor which could be surgically removed. He hypothesized that epilepsy was caused by an increase in ICP and believed that drainage of cerebrospinal fluid could cure epilepsy.[9]

The Japanese surgeon Hayazo Ito came to Bern in 1896 in order to perform experimental research on epilepsy. Kocher was especially interested in the ICP during experimentally induced epilepsy and after Ito returned to Japan, he performed over 100 surgeries in epilepsy patients.[9]

The American surgeon Harvey Cushing spent several months in the lab of Kocher in 1900, performing cerebral surgery and first encountering the Cushing reflex which describes the relationship between blood pressure and intracranial pressure. Kocher later also found that decompressive craniectomy was an effective method to lower ICP.[7]

In his surgery textbook Chirurgische Operationslehre, Kocher dedicated 141 pages of 1060 pages to surgery of the nervous system. It included methods of exploration and decompression of the brain.[9]

Contributions to Thyroid surgery[edit]

Thyroid surgery, which was mostly performed as treatment of goitre with a complete thyroidectomy when possible, was considered a risky procedure when Kocher started his work. Some estimates put the mortality of thyroidectomy as high as 75% in 1872.[12] Indeed, the operation was believed to be one of the most dangerous operations and in France it was prohibited by the Academy of Medicine at the time.[12] Through application of modern surgical methods, such as antiseptic wound treatment and minimizing blood loss, and the famous slow and precise style of Kocher, he managed to reduce the mortality of this operation from an already low 18% (compared to contemporary standards) to less than 0.5% by 1912.[7] By then, Kocher had performed over 5000 thyroid excisions.[7] The success of Kocher's methods, especially when compared to operations performed by Theodor Billroth who was also performing thyroidectomies at that time, was described by William Stewart Halsted as follows:

I have pondered the question for many years and conclude that the explanation probably lies in the operative methods of the two illustrious surgeons. Kocher, neat and precise, operating in a relatively bloodless manner, scrupulously removed the entire thyroid gland doing little damage outside its capsule. Billroth, operating more rapidly and, as I recall, with less regard for the tissues and less concern for hemorrhage, might easily have removed the parathyroids or at least have interfered with their blood supply, and have left fragments of the thyroid.

— William Stewart Halsted, Halstead WS. The operative story of goitre. Johns Hopkins Hosp Rep 1919;19:71–257. – Quoted in Morris et al. [13]

Kocher and others later discovered that the complete removal of the thyroid could lead to cretinism (termed cachexia strumipriva by Kocher) caused by a deficiency of thyroid hormones. The phenomena was reported to Kocher first in 1874 by the general practitioner August Fetscherin[14] and later in 1882 by Jacques-Louis Reverdin together with his assistant Auguste Reverdin (1848–1908).[2] Reverdin met Kocher on 7 September in Geneva at the international hygienic congress (internationaler Hygienekongress) and expressed his concerns about complete removal of the thyroid to Kocher.[15] Kocher then tried to contact 77 of his 102 former patients and found signs of a physical and mental decay in those cases where he had removed the thyroid gland completely.[16] Ironically, it was his precise surgery that allowed Kocher to remove the thyroid gland almost completely and led to the severe side effects of cretinism.

Kocher came to the conclusion that a complete removal of the thyroid (as it was common to perform at the time because the function of the thyroid was not yet clear) was not advisable, a finding that he made public on 4 April 1883 in a lecture to the German Society of Surgery and also published in 1883 under the title Ueber Kropfexstirpation und ihre Folgen (English: About Thyroidectomies and their consequences).[17] Reverdin had already made his findings public on 13 September 1882[15] and published further articles on this topic in 1883; yet still Kocher never acknowledged Reverdin's priority in this discovery.[2][11] At the time, the reactions to Kocher's lecture were mixed, some people asserted that goitre and cretinism were different stages of same disease and that cretinism would have occurred independently of the removal of the thyroid in the cases which Kocher described.[15] In the long run however, these observations contributed to a more complete understanding of thyroid function and were one of the early hints of a connection between the thyroid and congenital cretinism. These findings finally enabled thyroid hormone replacement therapies for a variety of thyroid related diseases.[13]

Further contributions to science[edit]

Kocher published works on a number of subjects other than the thyroid gland, including hemostasis, antiseptic treatments, surgical infectious diseases, on gunshot wounds, acute osteomyelitis, the theory of strangulated hernia, and abdominal surgery. The prize money, from the Nobel prize he received, helped him to establish the Kocher Institute in Bern.

A number of instruments (for example the craniometer[18]) and surgical techniques (for example, the Kocher manoeuvre, and kocher incision) are named after him, as well as the Kocher-Debre-Semelaigne syndrome. The Kocher manoeuvre is still a standard practice in orthopaedics.[3] Kocher is also credited for the invention in 1882 of the Kocher's Surgical Clamp, which he used to prevent blood loss during surgery.[11]

One of his main works, Chirurgische Operationslehre (Text-Book of Operative Surgery [19]), was published through six editions and translated into many languages.[7]

During his life, Kocher published 249 articles and books and supervised more than 130 doctoral candidates.[3] He was rector of the university in 1878 and 1903.[5] He was president of the Bernese and the Swiss physicians association and co-founded the Swiss society for surgery in 1913 and became its first president.[5]

In 1904 or 1905 he built a private clinic called "Ulmenhof" which had space for 25 patients. Here Kocher catered to the wealthier patients, which in many cases were international.[5] He also treated the wife of Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya and operated on her in Bern (in 1913[20]).[11]

Legacy[edit]

Kocher was also a famous and loved teacher. During nearly 100 semesters he taught his knowledge to about 10 000 students of the University of Bern. He was able to inspire students and taught them to think clearly and logically. Specifically, Kocher also taught a generation of Jewish-Russian students who could not study in Russia.[5] This association with Russia has also led the Russian Geographical Society to name a volcano after him (in the area of Ujun-Choldongi [5] in Manchuria [11] ).

Among his many local and international students were Carl Arend (Bern), Oscar Bernhard (St. Moritz), Andrea Crotti (Ohio), Gustave Dardel (Bern), Carl Garré (Bonn), Gottlieb and Max Feurer (St. Gallen), Anton Fonio (Langnau), Walter Gröbly (Arbon), Carl Kaufmann (Zürich), Albert Kocher (Bern), Joseph Kopp (Luzern), Ernst Kummer (Geneva), Otto Lanz (Amsterdam), Edmond Lardy (Geneva) Jakob Lauper (Interlaken), Albert Lüthi (Thun), Hermann Matti (Bern), Charles Pettavel (Neuenburg), Paul Pfähler (Olten), Fritz de Quervain (La Chaux de Fonds / Basel / Bern), August Rickli (Langenthal), Ernst Rieben (Interlaken), August Rollier (Leysin), César Roux (Lausanne), Karl Schuler (Rorschach), Fritz Steinmann (Bern), Albert Vogel (Luzern), Hans Wildbolz (Bern) as well as the American neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing.[5] Other notable students of his include Hayazo Ito (1865–1929) and S. Berezowsky which also spread his techniques in their respective home-countries (Japan and Russia).[9][21]

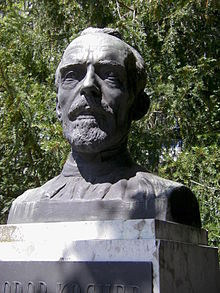

Kocher's name is living on with the Theodor Kocher Institute, the Kochergasse and the Kocher Park in Bern.[7] In the Inselspital, there is a bust of Kocher, created by Karl Hänny in 1927.[22] In the Kocher Park there is another bust, created by Max Fueter. In 1950, the Swiss historian Edgar Bonjour (1898–1991) who was married to Dora Kocher[23] wrote a 136-page monograph on Kocher's life that was extended again in 1981.[5]

Named in his honor[edit]

- The Kocher lunar crater named in his memory. [24]

- An asteroid (2087) Kocher also commemorates his name. [25]

Eponyms[edit]

- Kocher's forceps – a surgical instrument with serrated blades and interlocking teeth at the tips used to control bleeding[26]

- Kocher's point – common entry point for an intraventricular catheter to drain cerebral spinal fluid from the cerebral ventricles[27]

- Kocher manoeuvre – a surgical manoeuvre to expose structures in the retroperitoneum[28]

- Kocher–Debre–Semelaigne syndrome – hypothyroidism in infancy or childhood characterised by lower extremity or generalized muscular hypertrophy, myxoedema, short stature and cretinism[29]

- Kocher's incision – used in cholecystectomy[30]

- Kocher's incision II – is used in thyroid surgery[30]

- Kocher's sign – eyelid phenomenon in hyperthyroidism and Basedow's disease[30]

Honors[edit]

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1909)

- Hon FRCS (Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, 25 July 1900)[31]

- President of the Bernese and Swiss physician societies[5]

- President of the Swiss society for surgery[5]

- President of the German society for surgery (1902)[5]

- Honorary member of the German society for surgery (1902)[5]

- Chairman of the first international surgery conference in Brussels 1905[5]

- several honorary memberships and honorary doctorates[5]

Works[edit]

During his life, Kocher published 249 articles and books and supervised more than 130 doctoral candidates.[3] The following is an incomplete list of his most important works:

- Die antiseptische Wundbehandlung (Antiseptic wound treatment; 1881)

- Vorlesungen über chirurgische Infektionskrankheiten (Lectures on surgical infections; 1895)

- Chiruigische Operationslehre (1894; Eng. trans. as Textbook of Operative Surgery, 2 vols., 1911)

Notes[edit]

- ^ While the dissertation was published in 1866 and the HLS refers to 1866 as date of promotion and 1865 as date of completing his studies, all other sources point to 1865 as the date where Kocher obtained his doctorate

- ^ Choong (2009) claims that Kocher became assistant in Bern already in 1866 but according to Bonjour, Kocher was then still in Berlin

- ^ Several alternative spellings to Marie Witschi-Courant exist, for example Maria Witschi (ref hls), Witchi (ref choong2009), Witchi-Cournant (ref tan2008), Maria Witschi but in letters "Marie" (ref: Descriptor

- ^ The Bernese Burgerbibliothek give 1850–1925 as her living years and also Bonjour 1981 writes (pg 86) that she was nineteen in 1869 but does not give a date of death

References[edit]

- ^ "Kocher, Emil Theodor (1841–1917) in the Burgerbib". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koelbing, Huldrych M.F. "Kocher, Theodor im Historischen Lexikon der Schweis". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Gautschi, OP.; Hildebrandt, G.; Kocher, ET. (June 2009). "Emil Theodor Kocher (25/8/1841-27/7/1917)--A Swiss (neuro-)surgeon and Nobel Prize winner". Br J Neurosurg. 23 (3): 234–236. doi:10.1080/02688690902777658. PMID 19533456. S2CID 1622440.

- ^ "Kocher, Jakob Alexander (1814–1893) in the Burgerbib". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Bonjour, Edgar (1981) [1st. pub. in 1950 (http://d-nb.info/363374914)]. Theodor Kocher. Berner Heimatbücher (in German). 40/41 (2nd (2., stark erweiterte Auflage 1981) ed.). Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt. ISBN 978-3258030296.

- ^ Bonjour, Edgar (1950–1951). "Theodor Kocher". Schweizer Monatshefte : Zeitschrift für Politik, Wirtschaft, Kultur (in German). 30. doi:10.5169/seals-159844.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Choong, C.; Kaye, AH. (December 2009). "Emil theodor kocher (1841–1917)". J Clin Neurosci. 16 (12): 1552–1554. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2009.08.002. PMID 19815415. S2CID 13628110.

- ^ a b c "Kocher Biography on nobelprize.org". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrandt, G.; Surbeck, W.; Stienen, MN. (June 2012). "Emil Theodor Kocher: the first Swiss neurosurgeon". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 154 (6): 1105–1115, discussion 1115. doi:10.1007/s00701-012-1341-1. PMID 22492296. S2CID 12972792.

- ^ Tan, SY.; Shigaki, D. (September 2008). "Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917): thyroid surgeon and Nobel laureate" (PDF). Singapore Med J. 49 (9): 662–663. PMID 18830536.

- ^ a b c d e Gemsenjäger, Ernst (2011). "Milestones in European Thyroidology (MET) Theodor Kocher ( 1841–1917)". European Thyroid Association. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b Chiesa, F.; Kocher, ET. (December 2009). "The 100 years Anniversary of the Nobel Prize Award winner Emil Theodor Kocher, a brilliant far-sighted surgeon". Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 29 (6): 289. PMC 2868208. PMID 20463831.

- ^ a b Morris, J. B.; Schirmer, W. J. (1990). "The "right stuff": Five Nobel Prize-winning surgeons". Surgery. 108 (1): 71–80. PMID 2193425.

- ^ Hintzsche, E. (1970). "August Fetscherin (1849–1882), unjustly forgotten general practitioner". Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 100 (17): 721–727. PMID 4924042.

- ^ a b c Schlich, Thomas (1998). Die Erfindung der Organtransplantation: Erfolg und Scheitern des chirurgischen Organersatzes (1880–1930). Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag. pp. 35–91. ISBN 9783593359403. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Ulrich, Tröhler. "Towards endocrinology: Theodor Kocher's 1883 account of the unexpected effects of total ablation of the thyroid". JLL Bulletin: Commentaries on the history of treatment evaluation www.jameslindlibrary.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Kocher, Theodor. "Ueber Kropfexstirpation und ihre Folgen". Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 29: 254–337. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Schültke, Elisabeth (May 2009). "Theodor Kocher's craniometer". Neurosurgery. United States. 64 (5): 1001–1004, discussion 1004–5. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000344003.72056.7F. PMID 19404160.

- ^ Kocher, Theodor; Stiles, Harold Jalland (7 January 1895). Text-book of operative surgery. London : Adam and Charles Black. Retrieved 7 January 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Berühmte Berner und Bernerinnen - Emil Theodor Kocher". Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Whonamedit – Hayazo Ito". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Berchtold Weber: Historisch-topographisches Lexikon der Stadt Bern-Kochergasse Archived 25 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 1976, retrieved 6. September 2010

- ^ Kreis, Georg. "Bonjour, Edgar". HLS-DHS-DSS.CH. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Kocher". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ "(2087) Kocher".

- ^ "Medical Definition of KOCHER'S FORCEPS". www.Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Kocher's Point". Operative Neurosurgery. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Niederle, B. (6 December 2012). Surgery of the Biliary Tract: Old Problems New Methods, Current Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 36. ISBN 978-94-009-8213-0.

- ^ "APA Dictionary of Psychology". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Cadogan, Mike (1 March 2020). "Emil Theodor Kocher • Medical Eponym Library". Life in the Fast Lane Medical Blog. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Kocher, Theodor – Biographical entry – Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online". Retrieved 29 December 2012.

Further reading[edit]

- Gemsenjäger, Ernst (2011). "Milestones in European Thyroidology (MET) Theodor Kocher ( 1841–1917)". European Thyroid Association. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Emil Theodor Kocher on Nobelprize.org

including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1909 Concerning Pathological Manifestations in Low-Grade Thyroid Diseases

including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1909 Concerning Pathological Manifestations in Low-Grade Thyroid Diseases - "Kocher, Theodor – Biographical entry – Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online". Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1981) [1st. pub. in 1950 (http://d-nb.info/363374914)]. Theodor Kocher. Berner Heimatbücher (in German). 40/41 (2nd (2., stark erweiterte Auflage 1981) ed.). Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt. ISBN 978-3258030296.

- "Original Documents in the burgerbib". Retrieved 6 December 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment