Fencing

Final of the Challenge Réseau Ferré de France–Trophée Monal 2012, épée world cup tournament in Paris. | |

| Highest governing body | FIE |

|---|---|

| First played | Between the 17th and 19th centuries Europe |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Semi-contact |

| Team members | Singles or Team Relay |

| Mixed gender | Yes, separate |

| Type | indoor |

| Equipment | Épée, Foil, Sabre, Body cord, Lamé, Grip |

| Venue | Piste |

| Glossary | Glossary of fencing |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | Part of Summer Olympic programme since 1896 |

| Paralympic | part of Summer Paralympic programme since 1960 |

| |

| Also known as | Épée Fencing, Foil Fencing, Sabre Fencing |

|---|---|

| Focus | Weaponry |

| Hardness | Semi-Contact |

| Olympic sport | Present since inaugural 1896 Olympics |

| Official website | www.fie.ch www.fie.org |

Fencing[1] is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also saber); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, singlestick, appeared in the 1904 Olympics but was dropped after that, and is not a part of modern fencing. Fencing was one of the first sports to be played in the Olympics. Based on the traditional skills of swordsmanship, the modern sport arose at the end of the 19th century, with the Italian school having modified the historical European martial art of classical fencing, and the French school later refining the Italian system. There are three forms of modern fencing, each of which uses a different kind of weapon and has different rules; thus the sport itself is divided into three competitive scenes: foil, épée, and sabre. Most competitive fencers choose to specialize in one weapon only.

Competitive fencing is one of the five activities which have been featured in every modern Olympic Games, the other four being athletics, cycling, swimming, and gymnastics.

Competitive fencing

Governing body

Fencing is governed by Fédération Internationale d'Escrime (FIE). Today, its head office is in Lausanne, Switzerland. The FIE is composed of 145 national federations, each of which is recognised by its state Olympic Committee as the sole representative of Olympic-style fencing in that country.[2]

Rules

The FIE maintains the current rules[3] used by FIE sanctioned international events, including world cups, world championships and the Olympic Games. The FIE handles proposals to change the rules the first year after an Olympic year in the annual congress. The US Fencing Association has slightly different rules, but usually adheres to FIE standards.

History

Fencing traces its roots to the development of swordsmanship for duels and self defense. Fencing is believed to have originated in Spain; some of the most significant books on fencing were written by Spanish fencers. Treatise on Arms[4] was written by Diego de Valera between 1458 and 1471 and is one of the oldest surviving manuals on western fencing (in spite of the title, the book of Diego Valera was on heraldry, not about fencing)[5] shortly before dueling came under official ban by the Catholic Monarchs. In conquest, the Spanish forces carried fencing around the world, particularly to southern Italy, one of the major areas of strife between both nations.[6][7] Fencing was mentioned in the play The Merry Wives of Windsor written sometime prior to 1602.[8][9]

The mechanics of modern fencing originated in the 18th century in an Italian school of fencing of the Renaissance, and under their influence, were improved by the French school of fencing.[10][11] The Spanish school of fencing stagnated and was replaced by the Italian and French schools.

Development into a sport

The shift towards fencing as a sport rather than as military training happened from the mid-18th century, and was led by Domenico Angelo, who established a fencing academy, Angelo's School of Arms, in Carlisle House, Soho, London in 1763.[12] There, he taught the aristocracy the fashionable art of swordsmanship. His school was run by three generations of his family and dominated the art of European fencing for almost a century. [13]

He established the essential rules of posture and footwork that still govern modern sport fencing, although his attacking and parrying methods were still much different from current practice. Although he intended to prepare his students for real combat, he was the first fencing master to emphasize the health and sporting benefits of fencing more than its use as a killing art, particularly in his influential book L'École des armes (The School of Fencing), published in 1763.[13]

Basic conventions were collated and set down during the 1880s by the French fencing master Camille Prévost. It was during this time that many officially recognised fencing associations began to appear in different parts of the world, such as the Amateur Fencers League of America was founded in 1891, the Amateur Fencing Association of Great Britain in 1902, and the Fédération Nationale des Sociétés d'Escrime et Salles d'Armes de France in 1906.[14]

The first regularized fencing competition was held at the inaugural Grand Military Tournament and Assault at Arms in 1880, held at the Royal Agricultural Hall, in Islington in June. The Tournament featured a series of competitions between army officers and soldiers. Each bout was fought for five hits and the foils were pointed with black to aid the judges.[15] The Amateur Gymnastic & Fencing Association drew up an official set of fencing regulations in 1896.

Fencing was part of the Olympic Games in the summer of 1896. Sabre events have been held at every Summer Olympics; foil events have been held at every Summer Olympics except 1908; épée events have been held at every Summer Olympics except in the summer of 1896 because of unknown reasons.

Starting with épée in 1933, side judges were replaced by the Laurent-Pagan electrical scoring apparatus,[16] with an audible tone and a red or green light indicating when a touch landed. Foil was automated in 1956, sabre in 1988. The scoring box reduced the bias in judging, and permitted more accurate scoring of faster actions, lighter touches, and more touches to the back and flank than before.[17]

Weapons

There are three weapons in modern fencing: foil, épée, and sabre. Each weapon has its own rules and strategies. Equipment needed includes at least 2 swords, a lamé (not for épée), a white jacket, underarm protector, two body and mask cords, knee high socks, glove and knickers.

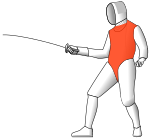

Foil

The foil is a light thrusting weapon with a maximum weight of 500 grams. The foil targets the torso, but not the arms or legs. The foil has a small circular hand guard that serves to protect the hand from direct stabs. As the hand is not a valid target in foil, this is primarily for safety. Touches are scored only with the tip; hits with the side of the blade do not register on the electronic scoring apparatus (and do not halt the action). Touches that land outside the target area (called an off-target touch and signaled by a distinct color on the scoring apparatus) stop the action, but are not scored. Only a single touch can be awarded to either fencer at the end of a phrase. If both fencers land touches within a close enough interval of milliseconds to register two lights on the machine, the referee uses the rules of "right of way" to determine which fencer is awarded the touch, or if an off-target hit has priority over a valid hit, in which case no touch is awarded. If the referee is unable to determine which fencer has right of way, no touch is awarded.

Épée

The épée is a thrusting weapon like the foil, but heavier, with a maximum total weight of 775 grams. In épée, the entire body is a valid target. The hand guard on the épée is a large circle that extends towards the pommel, effectively covering the hand, which is a valid target in épée. Like foil, all hits must be with the tip and not the sides of the blade. Hits with the side of the blade do not register on the electronic scoring apparatus (and do not halt the action). As the entire body is legal target, there is no concept of an off-target touch, except if the fencer accidentally strikes the floor, setting off the light and tone on the scoring apparatus. Unlike foil and sabre, épée does not use "right of way", and awards simultaneous touches to both fencers. However, if the score is tied in a match at the last point and a double touch is scored, the point is null and void.

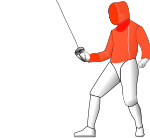

Sabre

The sabre is a light cutting and thrusting weapon that targets the entire body above the waist, except the weapon hand. Sabre is the newest weapon to be used. Like the foil, the maximum legal weight of a sabre is 500 grams. The hand guard on the sabre extends from hilt to the point at which the blade connects to the pommel. This guard is generally turned outwards during sport to protect the sword arm from touches. Hits with the entire blade or point are valid. As in foil, touches that land outside the target area are not scored. However, unlike foil, these off-target touches do not stop the action, and the fencing continues. In the case of both fencers landing a scoring touch, the referee determines which fencer receives the point for the action, again through the use of "right of way".

Equipment

Protective clothing

Most personal protective equipment for fencing is made of tough cotton or nylon. Kevlar was added to top level uniform pieces (jacket, breeches, underarm protector, lamé, and the bib of the mask) following the death of Vladimir Smirnov at the 1982 World Championships in Rome. However, Kevlar is degraded by both ultraviolet light and chlorine, which can complicate cleaning.

Other ballistic fabrics, such as Dyneema, have been developed that resist puncture, and which do not degrade the way that Kevlar does. FIE rules state that tournament wear must be made of fabric that resists a force of 800 newtons (180 lbf), and that the mask bib must resist twice that amount.

The complete fencing kit includes:

- Jacket

- The jacket is form-fitting, and has a strap (croissard) that passes between the legs. In sabre fencing, jackets are cut along the waist.[clarification needed] A small gorget of folded fabric is sewn in around the collar to prevent an opponent's blade from slipping under the mask and along the jacket upwards towards the neck. Fencing instructors may wear a heavier jacket, such as one reinforced by plastic foam, to deflect the frequent hits an instructor endures.

- Plastron

- A plastron is an underarm protector worn underneath the jacket. It provides double protection on the side of the sword arm and upper arm. There is no seam under the arm, which would line up with the jacket seam and provide a weak spot.

- Glove

- The sword hand is protected by a glove with a gauntlet that prevents blades from going up the sleeve and causing injury. The glove also improves grip.

- Breeches

- Breeches or knickers are short trousers that end just below the knee. The breeches are required to have 10 cm of overlap with the jacket. Most are equipped with suspenders (braces).

- Socks

- Fencing socks are long enough to cover the knee; some cover most of the thigh.

- Shoes

- Fencing shoes have flat soles, and are reinforced on the inside for the back foot, and in the heel for the front foot. The reinforcement prevents wear from lunging.

- Mask

- The fencing mask has a bib that protects the neck. The mask should support 12 kilograms (26 lb) on the metal mesh and 350 newtons (79 lbf) of penetration resistance on the bib. FIE regulations dictate that masks must withstand 25 kilograms (55 lb) on the mesh and 1,600 newtons (360 lbf) on the bib. Some modern masks have a see-through visor in the front of the mask. These have been used at high level competitions (World Championships etc.), however, they are currently banned in foil and épée by the FIE, following a 2009 incident in which a visor was pierced during the European Junior Championship competition. There are foil, sabre, and three-weapon masks.

- Chest protector

- A chest protector, made of plastic, is worn by female fencers and, sometimes, by males. Fencing instructors also wear them, as they are hit far more often during training than their students. In foil fencing, the hard surface of a chest protector decreases the likelihood that a hit registers.

- Lamé

- A lamé is a layer of electrically conductive material worn over the fencing jacket in foil and sabre fencing. The lamé covers the entire target area, and makes it easier to determine whether a hit fell within the target area. (In épée fencing the lamé is unnecessary, since the target area spans the competitor's entire body.) In sabre fencing, the lamé's sleeves end in a straight line across the wrist; in foil fencing, the lamé is sleeveless. A body cord is necessary to register scoring. It attaches to the weapon and runs inside the jacket sleeve, then down the back and out to the scoring box. In sabre and foil fencing, the body cord connects to the lamé in order to create a circuit to the scoring box.

- Sleeve

- An instructor or master may wear a protective sleeve or a leg leather to protect their fencing arm or leg, respectively.

- Elements of protective clothing

Traditionally, the fencer's uniform is white, and an instructor's uniform is black. This may be due to the occasional pre-electric practice of covering the point of the weapon in dye, soot, or colored chalk in order to make it easier for the referee to determine the placing of the touches. As this is no longer a factor in the electric era, the FIE rules have been relaxed to allow colored uniforms (save black). The guidelines also limit the permitted size and positioning of sponsorship logos.

Grips

Some pistol grips used by foil and épée fencers

Electric equipment

A set of electric fencing equipment is required to participate in electric fencing. Electric equipment in fencing varies depending on the weapon with which it is used in accordance. The main component of a set of electric equipment is the body cord. The body cord serves as the connection between a fencer and a reel of wire that is part of a system for electrically detecting that the weapon has touched the opponent. There are two types: one for épée, and one for foil and sabre.

Épée body cords consist of two sets of three prongs each connected by a wire. One set plugs into the fencer's weapon, with the other connecting to the reel. Foil and sabre body cords have only two prongs (or a twist-lock bayonet connector) on the weapon side, with the third wire connecting instead to the fencer's lamé. The need in foil and sabre to distinguish between on and off-target touches requires a wired connection to the valid target area.

A body cord consists of three wires known as the A, B, and C lines. At the reel connector (and both connectors for Épée cords) The B pin is in the middle, the A pin is 1.5 cm to one side of B, and the C pin is 2 cm to the other side of B. This asymmetrical arrangement ensures that the cord cannot be plugged in the wrong way around.

In foil, the A line is connected to the lamé and the B line runs up a wire to the tip of the weapon. The B line is normally connected to the C line through the tip. When the tip is depressed, the circuit is broken and one of three things can happen:

- The tip is touching the opponent's lamé (their A line): Valid touch

- The tip is touching the opponent's weapon or the grounded strip: nothing, as the current is still flowing to the C line.

- The tip is not touching either of the above: Off-target hit (white light).

In Épée, the A and B lines run up separate wires to the tip (there is no lamé). When the tip is depressed, it connects the A and B lines, resulting in a valid touch. However, if the tip is touching the opponents weapon (their C line) or the grounded strip, nothing happens when it is depressed, as the current is redirected to the C line. Grounded strips are particularly important in Épée, as without one, a touch to the floor registers as a valid touch (rather than off-target as in Foil).

In Sabre, similarly to Foil, the A line is connected to the lamé, but both the B and C lines are connected to the body of the weapon. Any contact between the one's B/C line (doesn't matter which, as they are always connected) and the opponent's A line (their lamé) results in a valid touch. There is no need for grounded strips in Sabre, as hitting something other than the opponent's lame does nothing.

In a professional fencing competition, a complete set of electric equipment is needed.

A complete set of foil electric equipment includes:

- An electric body cord, which runs under the fencer's jacket on his/her dominant side.

- An electric blade.

- A conductive lamé or electric vest.

- A conductive bib (often attached to the mask).

- An electric mask cord, connecting the conductive bib and the lamé.

The electric equipment of sabre is very similar to that of foil. In addition, equipment used in sabre includes:

- A larger conductive lame.

- An electric sabre.

- A completely conductive mask.

- A conductive glove or overlay.

Épée fencers lack a lamé, conductive bib, and head cord due to their target area. Also, their body cords are constructed differently as described above. However, they possess all of the other components of a foil fencer's equipment.

Techniques

Techniques or movements in fencing can be divided into two categories: offensive and defensive. Some techniques can fall into both categories (e.g. the beat). Certain techniques are used offensively, with the purpose of landing a hit on your opponent while holding the right of way (foil and sabre). Others are used defensively, to protect against a hit or obtain the right of way.[18]

The attacks and defences may be performed in countless combinations of feet and hand actions. For example, fencer A attacks the arm of fencer B, drawing a high outside parry; fencer B then follows the parry with a high line riposte. Fencer A, expecting that, then makes his own parry by pivoting his blade under fencer B's weapon (from straight out to more or less straight down), putting fencer B's tip off target and fencer A now scoring against the low line by angulating the hand upwards.

Whenever a point is scored, the fencers will go back to their starting mark. The fight will start again after the following commands have been given by the referee (in French in international settings): "En garde" (On guard), "Êtes-vous prêts ?" (Are you ready?), "Allez" (Fence!).

Offensive

- Attack: A basic fencing technique, also called a thrust, consisting of the initial offensive action made by extending the arm and continuously threatening the opponent's target. They are four different attacks (straight thrust, disengage attack, counter-disengage attack and cutover) In sabre, attacks are also made with a cutting action.

- Riposte: An attack by the defender after a successful parry. After the attacker has completed their attack, and it has been parried, the defender then has the opportunity to make an attack, and (at foil and sabre) take right of way.

- Feint: A false attack with the purpose of provoking a reaction from the opposing fencer.

- Lunge: A thrust while extending the front leg by using a slight kicking motion and propelling the body forward with the back leg.

- Beat attack: In foil and sabre, the attacker beats the opponent's blade to gain priority (right of way) and continues the attack against the target area. In épée, a similar beat is made but with the intention to disturb the opponent's aim and thus score with a single light.

- Disengage: A blade action whereby the blade is moved around the opponent's blade to threaten a different part of the target or deceive a parry.

- Compound attack: An attack preceded by one or more feints which oblige the opponent to parry, allowing the attacker to deceive the parry.

- Continuation/renewal of Attack: A typical épée action of making a 2nd attack after the first attack is parried. This may be done with a change in line; for example, an attack in the high line (above the opponent's bellguard, such as the shoulder) is then followed with an attack to the low line (below the opponent's bellguard, such as the thigh, or foot); or from the outside line (outside the bellguard, such as outer arm) to the inside line (inside the bellguard, such as the inner arm or the chest). A second continuation is stepping slight past the parry and angulating the blade to bring the tip of the blade back on target. A renewal may also be direct (without a change of line or any further blade action), in which case it is called a remise. In foil or sabre, a renewal is considered to have lost right of way, and the defender's immediate riposte, if it lands, will score instead of the renewal.

- Flick: a technique used primarily in foil and épée. It takes advantage of the extreme flexibility of the blade to use it like a whip, bending the blade so that it curves over and strikes the opponent with the point; this allows the fencer to hit an obscured part of the target (e.g., the back of the shoulder or, at épée, the wrist even when it is covered by the guard). This technique has become much more difficult due to timing changes which require the point to stay depressed for longer to set off the light.

Defensive

- Parry: Basic defence technique, block the opponent's weapon while it is preparing or executing an attack to deflect the blade away from the fencer's valid area and (in foil and sabre) to give fencer the right of way. Usually followed by a riposte, a return attack by the defender.

- Circle parry: A parry where the weapon is moved in a circle to catch the opponent's tip and deflect it away.

- Counter attack: A basic fencing technique of attacking your opponent while generally moving back out of the way of the opponent's attack. Used quite often in épée to score against the attacker's hand/arm. More difficult to accomplish in foil and sabre unless one is quick enough to make the counterattack and retreat ahead of the advancing opponent without being scored upon, or by evading the attacking blade via moves such as the In Quartata (turning to the side) or Passata-sotto (ducking). Counterattacks can also be executed in opposition, grazing along the opponent's blade and deflecting it to cause the attack to miss.

- Point-in-line: A specific position where the arm is straight and the point is threatening the opponent's target area. In foil and sabre, this gives one priority if the extension is completed before the opponent begins the final action of their attack. When performed as a defensive action, the attacker must then disturb the extended weapon to re-take priority; otherwise the defender has priority and the point-in-line will win the touch if the attacker does not manage a single light. In épée, there is no priority; the move may be used as a means by either fencer to achieve a double-touch and advance the score by 1 for each fencer. In all weapons, the point-in-line position is commonly used to slow the opponent's advance and cause them to delay the execution of their attack.

Universities and schools

University students compete internationally at the World University Games. The United States holds two national level university tournaments including the NCAA championship and the USACFC National Championships[19] tournaments in the US and the BUCS fencing championships in the United Kingdom.

National fencing organisations have set up programmes to encourage more students to fence. Examples include the Regional Youth Circuit program[20] in the US and the Leon Paul Youth Development series in the UK.

In recent years, attempts have been made to introduce fencing to a wider and younger audience, by using foam and plastic swords, which require much less protective equipment. This makes it much less expensive to provide classes, and thus easier to take fencing to a wider range of schools than traditionally has been the case. There is even a competition series in Scotland – the Plastic-and-Foam Fencing FunLeague[21] – specifically for Primary and early Secondary school-age children using this equipment.

The UK hosts two national competitions in which schools compete against each other directly: the Public Schools Fencing Championship, a competition only open to Independent Schools,[22] and the Scottish Secondary Schools Championships, open to all secondary schools in Scotland. It contains both teams and individual events and is highly anticipated. Schools organise matches directly against one another and school age pupils can compete individually in the British Youth Championships.

Many universities in Ontario, Canada have fencing teams that participate in an annual inter-university competition called the OUA Finals.

Other variants

Other variants include wheelchair fencing for those with disabilities, chair fencing, one-hit épée (one of the five events which constitute modern pentathlon) and the various types of non-Olympic competitive fencing.[23] Chair fencing is similar to wheelchair fencing, but for the able bodied. The opponents set up opposing chairs and fence while seated; all the usual rules of fencing are applied. An example of the latter is the American Fencing League (distinct from the United States Fencing Association): the format of competitions is different and the right of way rules are interpreted in a different way. In a number of countries, school and university matches deviate slightly from the FIE format. A variant of the sport using toy lightsabers earned national attention when ESPN2 acquired the rights to a selection of matches and included it as part of its "ESPN8: The Ocho" programming block in August 2018.[24]

In popular culture

One of the most notable films related to fencing is the 2015 Finnish-Estonian-German film The Fencer, directed by Klaus Härö, which is loosely based on the life of Endel Nelis, an accomplished Estonian fencer and coach.[25] The film was nominated for the 73rd Golden Globe Awards in the Foreign Language Film Category.[26]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Fencing".

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL FENCING FEDERATION". fie.org.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL FENCING FEDERATION". fie.ch.

- ^ Diego de Valera (1515*). Tratado delos rieptos [et] desafios que entre los caualleros [et] hijos dalgo se acostu[m]bran hazer segun las costu[m]bres de España, Francia [et] Ynglaterra: enel qual se contiene quales y quantos son los casos de traycion [et] de menos valer [et] las enseñas [et] cotas darmas. Alfonso de Orta. pp. 46–. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ "I.33 Medieval German Sword & Buckler Manual". ARMA. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ^ A History of Fencing. Hcs.harvard.edu. Retrieved on 2012-05-16.

- ^ Historia de la Esgrima Archived 2012-11-21 at the Wayback Machine. Educar.org (1999-02-22). Retrieved on 2012-05-16.

- ^ "1500s - Fencing history - About fencing - FIE - International Fencing Federation". fie.org. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ^ "Dates and sources - The Merry Wives of Windsor - Royal Shakespeare Company". www.rsc.org.uk.

- ^ Fencing Online Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Fencing.net. Retrieved on 2012-05-16.

- ^ A History of Fencing Archived 2012-09-06 at the Wayback Machine. Library.thinkquest.org. Retrieved on 2012-05-16.

- ^ F.H.W. Sheppard, ed. Survey of London volume 33 The Parish of St. Anne, Soho (north of Shaftesbury Avenue), London County Council, London: University of London, 1966, pp. 143–48, online at British History Online.

- ^ a b Nick Evangelista (1995). The Encyclopedia of the Sword. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 20–23.

- ^ "Fencing".

- ^ Malcolm Fare. "THE DEVELOPMENT OF FENCING WEAPONS".

- ^ Alaux, Michel. Modern Fencing: Foil, Epee, and Sabre. Scribner's, 1975, p. 83.

- ^ Freudenrich, Craig (21 Sep 2000). "How Fencing Equipment Works". How Stuff Works.

- ^ Bhutta, Omar (2016). "USA Fencing Rules" (PDF). United States Fencing Association.

- ^ USACFC.in 's USACFC. Retrieved on 2012-05-16.

- ^ US Fencing Youth Development Website, Regional Youth Circuit Archived 2007-07-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The Plastic-and-Foam Fencing FunLeague website.

- ^ Home :: Public Schools Fencing Championships.

- ^ "U.S. Paralympics | Sports | Wheelchair Fencing". Team USA. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Steinberg, Brian (August 8, 2018). "Bold strategy, Cotton: Inside ESPN's crazy plans to turn 'The Ocho' into a business". Variety. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

ESPN had to acquire the rights to show two of the most random events on the schedule (...) and high-level light-saber dueling.

- ^ Reiljan, Kaire (2015-03-16). ""Vehkleja". Kaks lugu, elu ja tõde filmis" ["The Fencer". Two stories, life and truth in film] (in Estonian). Lääne Elu. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ^ The Fencer – Golden Globes

References

- Amberger, Johann Christoph (1999). The Secret History of the Sword. Burbank: Multi-Media. ISBN 1-892515-04-0

- British Fencing (September 2008). "FIE Competition Rules (English)". Official document. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Evangelista, Nick (1996). The Art and Science of Fencing. Indianapolis: Masters Press. ISBN 1-57028-075-4.

- Evangelista, Nick (2000). The Inner Game of Fencing: Excellence in Form, Technique, Strategy, and Spirit. Chicago: Masters Press. ISBN 1-57028-230-7.

- Gaugler, William M. (2004). "The Science of Fencing: A Comprehensive Training Manual for Master and Student: Including Lesson Plans for Foil, Sabre and Epee Instruction". Laureate Press. ISBN 1884528309.

- United States Fencing Association (September 2010). United States Fencing Association Rules for Competition. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- Vass, Imre (2011). "Epee Fencing: A Complete System". SKA SwordPlay Books. ISBN 0978902270.

External links

| Look up fencing in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to fencing. |

- FIE Statutes

- Fencing at Curlie

- Fencing FAQ from rec.sport.fencing

- Links to videos of basic fencing moves from MIT OpenCourseWare as taught in Spring 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment