Federalism

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Federalism is a mixed or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (provincial, state, cantonal, territorial or other sub-unit governments) in a single political system. Its distinctive feature, first embodied in the Constitution of the United States of 1789, is a relationship of parity between the two levels of government established.[1] It can thus be defined as a form of government in which powers are divided between two levels of government of equal status.[2]

Federalism differs from confederalism, in which the general level of government is subordinate to the regional level, and from devolution within a unitary state, in which the regional level of government is subordinate to the general level.[3] It represents the central form in the pathway of regional integration or separation, bounded on the less integrated side by confederalism and on the more integrated side by devolution within a unitary state.[4][5]

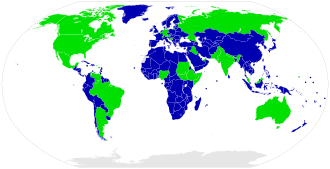

Examples of the federation or federal state include the United States, India, Brazil, Malaysia, Mexico, Russia, Germany, Canada, Switzerland, Argentina, Nigeria, and Australia. Some characterize the European Union as the pioneering example of federalism in a multi-state setting, in a concept termed the federal union of states.[6]

Overview[edit]

The terms "federalism" and "confederalism" both have a root in the Latin word foedus, meaning "treaty, pact or covenant". Their common meaning until the late eighteenth century was a simple league or inter-governmental relationship among sovereign states based upon a treaty. They were therefore initially synonyms. It was in this sense that James Madison in Federalist 39 had referred to the new US Constitution as "neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both" (i.e. as constituting neither a single large unitary state nor a league/confederation among several small states, but a hybrid of the two).[7] In the course of the nineteenth century the meaning of federalism would come to shift, strengthening to refer uniquely to the novel compound political form established at Philadelphia, while the meaning of confederalism would remain at a league of states.[8] Thus, this article relates to the modern usage of the word "federalism".

Modern federalism is a system based upon democratic rules and institutions in which the power to govern is shared between national and provincial/state governments. The term federalist describes several political beliefs around the world depending on context. Since the term federalization also describes distinctive political processes, its use as well depends on the context.[9]

In political theory, two main types of federalization are recognized:

- integrative,[10] or aggregative federalization,[11] designating various processes like: integration of non-federated political subjects by creating a new federation, accession of non-federated subjects into an existing federation, or transformation of a confederation into a federation

- devolutive,[10] or dis-aggregative federalization:[12] transformation of a unitary state into a federation

Federalism is sometimes viewed in the context of international negotiation as "the best system for integrating diverse nations, ethnic groups, or combatant parties, all of whom may have cause to fear control by an overly powerful center."[13] However, in some countries, those skeptical of federal prescriptions believe that increased regional autonomy is likely to lead to secession or dissolution of the nation.[13] In Syria, federalization proposals have failed in part because "Syrians fear that these borders could turn out to be the same as the ones that the fighting parties have currently carved out."[13]

Federations such as Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia collapsed as soon as it was possible to put the model to the test.[14]

Early origins[edit]

An early historical example of federalism is the Achaean League in Hellenistic Greece. Unlike the Greek city states of Classical Greece, each of which insisted on keeping its complete independence, changing conditions in the Hellenistic period drove many city states to band together even at the cost of losing part of their sovereignty – similar to the process leading to the formation of later federations.

Explanations for adoption[edit]

According to Daniel Ziblatt's Structuring the State, there are four competing theoretical explanations in the academic literature for the adoption of federal systems:

- Ideational theories, which hold that a greater degree of ideological commitment to decentralist ideas in society makes federalism more likely to be adopted.

- Cultural-historical theories, which hold that federal institutions are more likely to be adopted in societies with culturally or ethnically fragmented populations.

- "Social contract" theories, which hold that federalism emerges as a bargain between a center and a periphery where the center is not powerful enough to dominate the periphery and the periphery is not powerful enough to secede from the center.

- "Infrastructural power" theories, which hold that federalism is likely to emerge when the subunits of a potential federation already have highly developed infrastructures (e.g. they are already constitutional, parliamentary, and administratively modernized states).[15]

Immanuel Kant[edit]

Immanuel Kant was an advocate of federalism, noting that "the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils" so long as they possess an appropriate constitution which pits opposing factions against each other with a system of checks and balances. In particular individual states required a federation as a safeguard against the possibility of war.[16]

Examples[edit]

Europe vs. the United States[edit]

In Europe, "Federalist" is sometimes used to describe those who favor a common federal government, with distributed power at regional, national and supranational levels. Most European federalists want this development to continue within the European Union.[17] European federalism originated in post-war Europe; one of the more important initiatives was Winston Churchill's speech in Zürich in 1946.[18]

In the United States, federalism originally referred to belief in a stronger central government. When the U.S. Constitution was being drafted, the Federalist Party supported a stronger central government, while "Anti-Federalists" wanted a weaker central government. This is very different from the modern usage of "federalism" in Europe and the United States. The distinction stems from the fact that "federalism" is situated in the middle of the political spectrum between a confederacy and a unitary state. The U.S. Constitution was written as a reaction to the Articles of Confederation, under which the United States was a loose confederation with a weak central government.

In contrast, Europe has a greater history of unitary states than North America, thus European "federalism" argues for a weaker central government, relative to a unitary state. The modern American usage of the word is much closer to the European sense. As the power of the Federal government has increased, some people[who?] have perceived a much more unitary state than they believe the Founding Fathers intended. Most people politically advocating "federalism" in the United States argue in favor of limiting the powers of the federal government, especially the judiciary (see Federalist Society, New Federalism).

In Canada, federalism typically implies opposition to sovereigntist movements (most commonly Quebec separatism).

The governments of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, India, and Mexico, among others, are also organized along federalist principles.

Federalism may encompass as few as two or three internal divisions, as is the case in Belgium or Bosnia and Herzegovina. In general, two extremes of federalism can be distinguished: at one extreme, the strong federal state is almost completely unitary, with few powers reserved for local governments; while at the other extreme, the national government may be a federal state in name only, being a confederation in actuality.

In 1999, the Government of Canada established the Forum of Federations as an international network for exchange of best practices among federal and federalizing countries. Headquartered in Ottawa, the Forum of Federations partner governments include Australia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan and Switzerland.

Anarchism[edit]

Anarchists are against the state, but they are not against political organization or "governance", so long as it is self-governance utilizing direct democracy. The mode of political organization preferred by anarchists, in general, is federalism or confederalism. However, the anarchist definition of federalism tends to differ from the definition of federalism assumed by pro-state political scientists. The following is a brief description of federalism from section I.5 of An Anarchist FAQ:

- "The social and political structure of anarchy is similar to that of the economic structure, i.e., it is based on a voluntary federation of decentralized, directly democratic policy-making bodies. These are the neighborhood and community assemblies and their confederations. In these grassroots political units, the concept of "self-management" becomes that of "self-government", a form of municipal organisation in which people take back control of their living places from the bureaucratic state and the capitalist class whose interests it serves.

- [...]

- The key to that change, from the anarchist standpoint, is the creation of a network of participatory communities based on self-government through direct, face-to-face democracy in grassroots neighborhood and community assemblies [meetings for discussion, debate, and decision making].

- [...]

- Since not all issues are local, the neighborhood and community assemblies will also elect mandated and re-callable delegates to the larger-scale units of self-government in order to address issues affecting larger areas, such as urban districts, the city or town as a whole, the county, the bio-region, and ultimately the entire planet. Thus the assemblies will confederate at several levels in order to develop and co-ordinate common policies to deal with common problems.

- [...]

- This need for co-operation does not imply a centralized body. To exercise your autonomy by joining self-managing organisations and, therefore, agreeing to abide by the decisions you help make is not a denial of that autonomy (unlike joining a hierarchical structure, where you forsake autonomy within the organisation). In a centralized system, we must stress, power rests at the top and the role of those below is simply to obey (it matters not if those with the power are elected or not, the principle is the same). In a federal system, power is not delegated into the hands of a few (obviously a "federal" government or state is a centralized system). Decisions in a federal system are made at the base of the organisation and flow upwards so ensuring that power remains decentralized in the hands of all. Working together to solve common problems and organize common efforts to reach common goals is not centralization and those who confuse the two make a serious error – they fail to understand the different relations of authority each generates and confuse obedience with co-operation."[19]

Christian Church[edit]

Federalism also finds expression in ecclesiology (the doctrine of the church). For example, presbyterian church governance resembles parliamentary republicanism (a form of political federalism) to a large extent. In Presbyterian denominations, the local church is ruled by elected elders, some of which are ministerial. Each church then sends representatives or commissioners to presbyteries and further to a general assembly. Each greater level of assembly has ruling authority over its constituent members. In this governmental structure, each component has some level of sovereignty over itself. As in political federalism, in presbyterian ecclesiology there is shared sovereignty.

Other ecclesiologies also have significant representational and federalistic components, including the more anarchic congregational ecclesiology, and even in more hierarchical episcopal ecclesiology.

Some Christians argue that the earliest source of political federalism (or federalism in human institutions; in contrast to theological federalism) is the ecclesiastical federalism found in the Bible. They point to the structure of the early Christian Church as described (and prescribed, as believed by many) in the New Testament. In their arguments, this is particularly demonstrated in the Council of Jerusalem, described in Acts chapter 15, where the Apostles and elders gathered together to govern the Church; the Apostles being representatives of the universal Church, and elders being such for the local church. To this day, elements of federalism can be found in almost every Christian denomination, some more than others.

Constitutional structure[edit]

Division of powers[edit]

In a federation, the division of power between federal and regional governments is usually outlined in the constitution. Almost every country allows some degree of regional self-government, in federations the right to self-government of the component states is constitutionally entrenched. Component states often also possess their own constitutions which they may amend as they see fit, although in the event of conflict the federal constitution usually takes precedence.

In almost all federations the central government enjoys the powers of foreign policy and national defense as exclusive federal powers. Were this not the case a federation would not be a single sovereign state, per the UN definition. Notably, the states of Germany retain the right to act on their own behalf at an international level, a condition originally granted in exchange for the Kingdom of Bavaria's agreement to join the German Empire in 1871. Beyond this the precise division of power varies from one nation to another. The constitutions of Germany and the United States provide that all powers not specifically granted to the federal government are retained by the states. The Constitution of some countries like Canada and India, state that powers not explicitly granted to the provincial governments are retained by the federal government. Much like the US system, the Australian Constitution allocates to the Federal government (the Commonwealth of Australia) the power to make laws about certain specified matters which were considered too difficult for the States to manage, so that the States retain all other areas of responsibility. Under the division of powers of the European Union in the Lisbon Treaty, powers which are not either exclusively of European competence or shared between EU and state as concurrent powers are retained by the constituent states.

Where every component state of a federation possesses the same powers, we are said to find 'symmetric federalism'. Asymmetric federalism exists where states are granted different powers, or some possess greater autonomy than others do. This is often done in recognition of the existence of a distinct culture in a particular region or regions. In Spain, the Basques and Catalans, as well as the Galicians, spearheaded a historic movement to have their national specificity recognized, crystallizing in the "historical communities" such as Navarre, Galicia, Catalonia, and the Basque Country. They have more powers than the later expanded arrangement for other Spanish regions, or the Spain of the autonomous communities (called also the "coffee for everyone" arrangement), partly to deal with their separate identity and to appease peripheral nationalist leanings, partly out of respect to specific rights they had held earlier in history. However, strictly speaking Spain is not a federation, but a decentralized administrative organization of states.

It is common that during the historical evolution of a federation there is a gradual movement of power from the component states to the centre, as the federal government acquires additional powers, sometimes to deal with unforeseen circumstances. The acquisition of new powers by a federal government may occur through formal constitutional amendment or simply through a broadening of the interpretation of a government's existing constitutional powers given by the courts.

Usually, a federation is formed at two levels: the central government and the regions (states, provinces, territories), and little to nothing is said about second or third level administrative political entities. Brazil is an exception, because the 1988 Constitution included the municipalities as autonomous political entities making the federation tripartite, encompassing the Union, the States, and the municipalities. Each state is divided into municipalities (municípios) with their own legislative council (câmara de vereadores) and a mayor (prefeito), which are partly autonomous from both Federal and State Government. Each municipality has a "little constitution", called "organic law" (lei orgânica). Mexico is an intermediate case, in that municipalities are granted full-autonomy by the federal constitution and their existence as autonomous entities (municipio libre, "free municipality") is established by the federal government and cannot be revoked by the states' constitutions. Moreover, the federal constitution determines which powers and competencies belong exclusively to the municipalities and not to the constituent states. However, municipalities do not have an elected legislative assembly.

Federations often employ the paradox of being a union of states, while still being states (or having aspects of statehood) in themselves. For example, James Madison (author of the US Constitution) wrote in Federalist Paper No. 39 that the US Constitution "is in strictness neither a national nor a federal constitution; but a composition of both. In its foundation, it is federal, not national; in the sources from which the ordinary powers of the Government are drawn, it is partly federal, and partly national..." This stems from the fact that states in the US maintain all sovereignty that they do not yield to the federation by their own consent. This was reaffirmed by the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which reserves all powers and rights that are not delegated to the Federal Government as left to the States and to the people.

Bicameralism[edit]

The structures of most federal governments incorporate mechanisms to protect the rights of component states. One method, known as 'intrastate federalism', is to directly represent the governments of component states in federal political institutions. Where a federation has a bicameral legislature the upper house is often used to represent the component states while the lower house represents the people of the nation as a whole. A federal upper house may be based on a special scheme of apportionment, as is the case in the senates of the United States and Australia, where each state is represented by an equal number of senators irrespective of the size of its population.

Alternatively, or in addition to this practice, the members of an upper house may be indirectly elected by the government or legislature of the component states, as occurred in the United States prior to 1913, or be actual members or delegates of the state governments, as, for example, is the case in the German Bundesrat and in the Council of the European Union. The lower house of a federal legislature is usually directly elected, with apportionment in proportion to population, although states may sometimes still be guaranteed a certain minimum number of seats.

Intergovernmental relations[edit]

In Canada, the provincial governments represent regional interests and negotiate directly with the central government. A First Ministers conference of the prime minister and the provincial premiers is the de facto highest political forum in the land, although it is not mentioned in the constitution.

Constitutional change[edit]

Federations often have special procedures for amendment of the federal constitution. As well as reflecting the federal structure of the state this may guarantee that the self-governing status of the component states cannot be abolished without their consent. An amendment to the constitution of the United States must be ratified by three-quarters of either the state legislatures, or of constitutional conventions specially elected in each of the states, before it can come into effect. In referendums to amend the constitutions of Australia and Switzerland it is required that a proposal be endorsed not just by an overall majority of the electorate in the nation as a whole, but also by separate majorities in each of a majority of the states or cantons. In Australia, this latter requirement is known as a double majority.

Some federal constitutions also provide that certain constitutional amendments cannot occur without the unanimous consent of all states or of a particular state. The US constitution provides that no state may be deprived of equal representation in the senate without its consent. In Australia, if a proposed amendment will specifically impact one or more states, then it must be endorsed in the referendum held in each of those states. Any amendment to the Canadian constitution that would modify the role of the monarchy would require unanimous consent of the provinces. The German Basic Law provides that no amendment is admissible at all that would abolish the federal system.

Other technical terms[edit]

- Fiscal federalism – the relative financial positions and the financial relations between the levels of government in a federal system.

- Formal federalism (or 'constitutional federalism') – the delineation of powers is specified in a written constitution, which may or may not correspond to the actual operation of the system in practice.

- Executive federalism refers in the English-speaking tradition to the intergovernmental relationships between the executive branches of the levels of government in a federal system and in the continental European tradition to the way constituent units 'execute' or administer laws made centrally.

- Gleichschaltung – the conversion from a federal governance to either a completely unitary or more unitary one, the term was borrowed from the German for conversion from alternating to direct current.[20] During the Nazi era the traditional German states were mostly left intact in the formal sense, but their constitutional rights and sovereignty were eroded and ultimately ended and replaced with the Gau system. Gleichschaltung also has a broader sense referring to political consolidation in general.

- defederalize – to remove from federal government, such as taking a responsibility from a national level government and giving it to states or provinces

Political philosophy[edit]

The meaning of federalism, as a political movement, and of what constitutes a 'federalist', varies with country and historical context.[citation needed] Movements associated with the establishment or development of federations can exhibit either centralising or decentralising trends.[citation needed] For example, at the time those nations were being established, factions known as "federalists" in the United States and Australia advocated the formation of strong central government. Similarly, in European Union politics, federalists mostly seek greater EU integration. In contrast, in Spain and in post-war Germany, federal movements have sought decentralisation: the transfer of power from central authorities to local units. In Canada, where Quebec separatism has been a political force for several decades, the "federalist" impulse aims to keep Quebec inside Canada.

Conflict reducing device[edit]

Federalism, and other forms of territorial autonomy, is generally seen[by whom?] as a useful way to structure political systems in order to prevent violence among different groups within countries because it allows certain groups to legislate at the subnational level.[21] Some scholars have suggested, however, that federalism can divide countries and result in state collapse because it creates proto-states.[22] Still others have shown that federalism is only divisive when it lacks mechanisms that encourage political parties to compete across regional boundaries.[23]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ In 1946, scholar Kenneth Wheare observed that the two levels of government in the US were "co-equally supreme". In this he echoed the perspective of the founding fathers, James Madison in Federalist 39 having seen the several states as forming "distinct and independent portions of the supremacy" in relation to the general government. Wheare, Kenneth (1946) Federal Government, Oxford University Press, London, pp.10–15. Madison, James, Hamilton, Alexander and Jay, John (1987) The Federalist Papers, Penguin, Harmondsworth, p.258.

- ^ Law, John (2013) "How Can We Define Federalism?", in Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.E105-6. http://www.on-federalism.eu/attachments/169_download.pdf

- ^ Wheare, Kenneth (1946), pp.31–2.

- ^ See diagram below.

- ^ Diamond, Martin (1961) "The Federalist's View of Federalism", in Benson, George (ed.) Essays in Federalism, Institute for Studies in Federalism, Claremont, p.22. Downs, William (2011) "Comparative Federalism, Confederalism, Unitary Systems", in Ishiyama, John and Breuning, Marijke (eds) Twenty-first Century Political Science: A Reference Handbook, Sage, Los Angeles, Vol. I, pp.168–9. Hueglin, Thomas and Fenna, Alan (2006) Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry, Broadview, Peterborough, p.31.

- ^ See Law, John (2013), p.104. http://www.on-federalism.eu/attachments/169_download.pdf

This author identifies two distinct federal forms, where before only one was known, based upon whether sovereignty (conceived in its core meaning of ultimate authority) resides in the whole (in one people) or in the parts (in many peoples). This is determined by the absence or presence of a unilateral right of secession for the parts. The structures are termed, respectively, the federal state (or federation) and the federal union of states (or federal union). - ^ Madison, James, Hamilton, Alexander and Jay, John (1987) The Federalist Papers, Penguin, Harmondsworth, p.259.

- ^ Law, John (2012) "Sense on Federalism", in Political Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 3, p.544.

- ^ Broschek 2016, p. 23-50.

- ^ a b Gerven 2005, p. 35, 392.

- ^ Broschek 2016, p. 27-28, 39.

- ^ Broschek 2016, p. 27-28, 39-41, 44.

- ^ a b c Michael Meyer-Resende, Why Talk of Federalism Won't Help Peace in Syria, Foreign Policy (March 18, 2017).

- ^ 'The Federal Experience in Yugoslavia', Mihailo Markovic, page 75; included in 'Rethinking Federalism: Citizens, Markets, and Governments in a changing world', edited by Karen Knop, Sylvia Ostry, Richard Simeon, Katherine Swinton|Google books

- ^ Daniel Ziblatt (2008). Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Kant: Political Writings, H.S. Reiss, 2013

- ^ https://www.federalists.eu/fileadmin/files_uef/Pictures/Website_Animation/About_UEF/70th_Anniversary/UEF_Booklet_70_Years_of_Campaigns_for_a_United_and_Federal_Europe.pdf

- ^ "The Churchill Society London. Churchill's Speeches". www.churchill-society-london.org.uk.

- ^ Anarchist Writers. "I.5 What could the social structure of anarchy look like?" An Anarchist FAQ. http://www.infoshop.org/page/AnarchistFAQSectionI5 Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Page 72 of Koonz, Claudia (2003). The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01172-4.

- ^ Arend Lijphart. 1977. Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

- ^ Henry E. Hale. Divided We Stand: Institutional Sources of Ethnofederal State Survival and Collapse. World Politics 56(2): 165–193.

- ^ Dawn Brancati. 2009. Peace by Design: Managing Intrastate Conflict through Decentralization. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Sources[edit]

- Bednar, Jenna (2011). "The Political Science of Federalism". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 7: 269–288. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105522.

- Broschek, Jorg (2016). "Federalism in Europe, America and Africa: A Comparative Analysis". Federalism and Decentralization: Perceptions for Political and Institutional Reforms (PDF). Singapore: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. pp. 23–50.

- Gerven, Walter van (2005). The European Union: A Polity of States and Peoples. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804750646.

External links[edit]

| Look up federalism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Federalism. |

- P.-J. Proudhon, The Principle of Federation, 1863.

- A Comparative Bibliography: Regulatory Competition on Corporate Law

- A Rhetoric for Ratification: The Argument of the Federalist and its Impact on Constitutional Interpretation

- Brainstorming National (in French)

- Teaching about Federalism in the United States – From the Education Resources Information Center Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Bloomington, Indiana.

- An Ottawa, Ontario, Canada-based international organization for federal countries that share best practices among countries with that system of government

- Tenth Amendment Center Federalism and States Rights in the U.S.

- BackStory Radio episode on the origins and current status of Federalism

- Constitutional law scholar Hester Lessard discusses Vancouver's Downtown Eastside and jurisdictional justice McGill University, 2011

- General Federalism

No comments:

Post a Comment