History of Guam

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The history of Guam involves phases including the early arrival of Austronesian people known today as the Chamorros around 2000 BCE, the development of "pre-contact" society, Spanish colonization in the 17th century and the present American rule of the island since the 1898 Spanish–American War. Guam's history of colonialism is the longest among the Pacific islands.

Guam prior to European contact[edit]

Migrations[edit]

The Mariana Islands were the first islands settled by humans in Remote Oceania. Incidentally it is also the first and the longest of the ocean-crossing voyages of the Austronesian peoples into Remote Oceania, and is separate from the later Polynesian settlement of the rest of Remote Oceania. They were first settled around 1500 to 1400 BCE by migrants departing from the Philippines.[1][2]

Archeological studies of human activity on the islands has revealed potteries with red-slipped, circle-stamped and punctate-stamped designs found in the Mariana Islands dating between 1500 and 1400 BC. These artifacts show similar aesthetics to pottery found in Northern and Central Philippines, the Nagsabaran (Cagayan Valley) pottery, which flourished during the period between 2000 and 1300 BC.[1]

Comparative and historical linguistics also indicate that the Chamorro language is most closely related to the Philippine subfamily of the Austronesian languages, instead of the Oceanic subfamily of the languages of the rest of Remote Oceania.[1][3]

Mitchondrial DNA and whole genome sequencing of the Chamorro people strongly support an ancestry from the Philippines. Genetic analysis of pre-Latte period skeletons in Guam also show that they do not have Australo-Melanesian ("Papuan") ancestry which rules out origins from the Bismarck Archipelago, New Guinea, or eastern Indonesia. The Lapita culture itself (the ancestral branch of the Polynesian migrations) is younger than the first settlement of the Marianas (the earliest Lapita artifacts are dated to around 1350 to 1300 BCE), indicating that they originated from separate migration voyages.[4][5]

Nevertheless, DNA analysis also show close genetic relationship between ancient settlers of the Marianas and early Lapita settlers in the Bismarck Archipelago. This may indicate that both the Lapita culture and the Marianas were settled from direct migrations from the Philippines, or that early settlers from the Marianas voyaged further southwards into the Bismarcks and reconnected with the Lapita people.[4]

The Marianas also later established contact and received migrations from the Caroline Islands at around the first millennium CE. This brought new pottery styles, language, genes, and the hybrid Polynesian breadfruit.[6]

The period 900 to 1700 CE of the Marianas, immediately before and during the Spanish colonization, is known as the Latte period. It is characterized by rapid cultural change, most notably by the massive megalithic latte stones (also spelled latde or latti). These were composed of the haligi pillars capped with another stone called tasa (which prevented rodents from climbing the posts). These served as supports for the rest of the structure which was made of wood. Remains of structures made with similar wooden posts have also been found. Human graves have also been found in front of latte structures, The Latte period was also characterized by the introduction of rice agriculture, which is unique in the pre-contact Pacific Islands.[7]

The reasons for these changes are still unclear, but it is believed that it may have resulted from a third wave of migrants from Island Southeast Asia. Comparisons with other architectural traditions makes it likely that this third migration wave were again from the Philippines, or from eastern Indonesia (either Sulawesi or Sumba), all of which have a tradition of raised buildings with capstones. Interestingly, the word haligi ("pillar") is also used in various languages throughout the Philippines; while the Chamorro word guma ("house") closely resembles the Sumba word uma.[7]

Ancient Chamorro society[edit]

Most of what is known about Pre-Contact ("Ancient") Chamorros comes from legends and myths, archaeological evidence, Jesuit missionary accounts, and observations from visiting scientists like Otto von Kotzebue and Louis de Freycinet.

When Europeans first arrived on Guam, Chamorro society roughly fell into three classes: matao (upper class), achaot (middle class), and mana'chang (lower class). The matao were located in the coastal villages, which meant they had the best access to fishing grounds while the mana'chang were located in the interior of the island. Matao and mana'chang rarely communicated with each other, and matao often used achaot as a go-between.

There were also "makhanas" (shamans) and "suruhanus" (herb doctors), skilled in healing and medicine.[8]Belief in spirits of ancient Chamorros called Taotao Mona still persists as remnant of pre-European society. Early European explorers noted the Chamorros' fast sailing vessels used for trading with other islands of Micronesia.

Latte[edit]

The "latte stones" familiar to Guam residents and visitors alike were in fact a recent development in Pre-Contact Chamorro society. The latte stone consists of a head and a base shaped out of limestone. Like the Easter Island Moai statues, there is plenty of speculation over how this was done by a society without machines or metal, but the generally accepted view is that the head and base were etched out of the ground by sharp adzes and picks (possibly with the use of fire), and carried to the assembly area by an elaborate system of ropes and logs. The latte stone was used as a part of the raised foundation for a magalahi (matao chief) house, although they may have also been used for canoe sheds.

Archaeologists using carbon-dating have broken Pre-Contact Guam (i.e. Chamorro) history into three periods: "Pre-Latte" (BC 2000? to AD 1) "Transitional Pre-Latte" (AD 1 to AD 1000), and "Latte" (AD 1000 to AD 1521). Archaeological evidence also suggests that Chamorro society was on the verge of another transition phase by 1521, as latte stones became bigger.

Assuming the stones were used for chiefly houses, it can be argued that Chamorro society was becoming more stratified, either from population growth or the arrival of new people. The theory remains tenuous, however, due to lack of evidence, but if proven correct, will further support the idea that Pre-Contact Chamorros lived in a vibrant and dynamic environment.

Spanish era[edit]

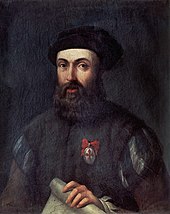

Magellan's first encounter with Guam[edit]

The first known contact between Guam and Western Europe occurred when a Spanish expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer sailing for the Holy Roman Emperor King Charles I of Spain, arrived with his 3-ship fleet in Guam on March 6, 1521 after a long voyage across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, from Spain. History credits the village of Umatac as his landing place, but drawings from the navigator's diary suggest that Magellan may have landed in Tumon in northern Guam. The expedition had started out in Spain with five ships. By the time they reached the Marianas they were down to three ships and nearly half the crew, due to storms, diseases and the mutiny in one ship which destroyed the expedition.[9] Tired and hungry from their long discovery voyage, the crew prepared to go ashore and restore provisions in Guam. However, the excited native Chamorros who had a different concept of ownership, based on subsistence living,[10]:30 canoed out to the ships and began helping themselves to everything that was not nailed down to the deck of the galleons. "The aboriginals were willing to engage in barter... Their love of gain overcame every other consideration."[11] As the Chamorros took everything they found on the ship without asking, Magellan and his crew remembered the island as the "Isla de Ladrones" (Island of Thieves). After a few shots were fired from the Trinidad's big guns, the natives were frightened off from the ship and retreated into the surrounding jungle. Magellan was eventually able to obtain rations and offered iron, a highly prized material, in exchange for fresh fruits, vegetables, and water. Details of this visit, the first in history between Westerners and a Pacific island people, come from the journal of Antonio Pigafetta, the expedition's scribe and one of only 18 crew members to eventually survive the circumnavigation of the globe, completed by Juan Sebastian Elcano.[9]

Spanish colonization[edit]

Despite Magellan's visit, Guam was not officially claimed by Spain until 1565 by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi. However, the island was not actually colonized until the 17th century.[12] On June 15, 1668, the galleon San Diego arrived at the shore of the island of Guam.[13] Jesuit missionaries led by Padre Diego Luis de San Vitores arrived on Guam to introduce Christianity and develop trade. The Spanish taught the Chamorros to cultivate maize (corn), raise cattle, and tan hides, as well as to adopt western-style clothing. They also introduced the Spanish language and culture. Once Christianity was established, the Catholic Church became the focal point for village activities, as in other Spanish cities. Since 1565, Guam became a regular port-of-call for the Spanish galleons that crossed the Pacific Ocean from Mexico to the Philippines.[14]

Chief Quipuha was the maga'lahi, or high ranking male, in the area of Hagåtña when the Spanish landed off its shores in 1668. Quipuha welcomed the missionaries and consented to be baptized by San Vitores as Juan Quipuha. Quipuha granted the lands on which the first Catholic Church in Guam, the Dulce Nombre de Maria {Sweet Name of Mary} Cathedral Basilica, was constructed in 1669. The original cathedral was destroyed during World War II and the present Cathedral, was constructed on the original site in 1955. Chief Quipuha died in 1669 but his policy of allowing the Spanish to establish a base on Guam had important consequences for the future of the island. It also facilitated the Manila Galleon trade.

A few years later, Jesuit priest Diego Luis de San Vitores and his assistant, Pedro Calungsod, were brutally killed by Chief Mata'pang of Tomhom (Tumon), allegedly for baptizing the Chief's baby girl without the Chief's consent. This was in April 1672. Many Chamorros at the time believed baptisms killed babies: because priests would baptize infants already near death (in the belief that this was the only way to save such children's souls), baptism seemed to many Chamorros to be the cause of death.[10]:49 San Vitores carried out his mission in a peaceful manner, preaching Christianity and moral values to the indigenous population. So when San Vitores was assassinated by Mata'pang, the Spanish forces attempted to capture the guilty. This led to a number of battles in which many Spanish and Chamorros died. Mata'pang himself was killed in a final battle on the Island of Rota in 1680.[14]

During the course of the Spanish administration of Guam, lower birth rates and diseases reduced the population from 12,000[10]:47 to roughly 5,000 by 1741[citation needed]. After 1695, Chamorros settled in five villages: Hagåtña, Agat, Umatac, Pago, and Fena. During this historical period, Spanish language and customs were introduced in the island and Catholicism became the predominant religion. The Spanish built infrastructures such as roads and ports, as well as schools and hospitals. Spanish and Filipinos, mostly men, increasingly intermarried with the Chamorros, particularly the new cultured or "high" people (manak'kilo) or gentry of the towns. In 1740, Chamorros of the Northern Mariana Islands, except Rota, were moved from some of their home islands to Guam. Documents from the Spanish period are the only historical sources about colonial and pre-colonial times in the island. As in the Philippines, Spanish scholars wrote about Chamorro culture and language, including dictionaries and anthropological reports which are of great historical value today.

The Galleon Era ended in 1815 following the Mexican Independence. Guam later was host to a number of scientists, voyagers, and whalers from Russia, France, and England who also provided detailed accounts of the daily life on Guam under Spanish rule. Through the Spanish colonial period, Guam inherited food, language, and surnames from Spain and Spanish America.[15]

Governors of Spanish Marianas[edit]

- Emilio Galisteo/Galintie (October 1893–December 1895)[16][17]

- Jacobo Marina (December 1895–February 1897)[16]

- Angel Nieto (Acting; February–April 1897)[18]

- Juan Marina (April 1897–June 1898)[18]

American era[edit]

Capture of Guam[edit]

On June 21, 1898, the United States captured Guam in a bloodless landing during the Spanish–American War. By the Treaty of Paris, Spain officially ceded the island to the United States.[10]:110–112 Guam became part of an American telegraph line to the Philippines, also ceded by the treaty;[19] a way station for American ships traveling to and from there; and an important part of the United States' War Plan Orange against Japan. Although Alfred Thayer Mahan, Robert Coontz, and others envisioned the island as "a kind of Gibraltar" in the Pacific, Congress repeatedly failed to fulfill the military's requests to fortify Guam; when a German warship was interned in 1914 before America's entry into World War I, its crew of 543 outnumbered their American custodians.[10]:131,133,135–136

The 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia said of Guam, "of its total population of 11,490 (11,159 natives), Hagåtña, the capital, contains about 8,000. Possessing a good harbor, the island serves as a United States naval station, the naval commandant acting also as governor. The products of the island are maize, copra, rice, sugar, and valuable timber." Military officers governed the island as "USS Guam", and the United States Navy opposed proposals for civilian government until 1950.[10]:125–126

World War II[edit]

During World War II, Guam was invaded by the Imperial Japanese Army on December 8, 1941 shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese immediately renamed the island "Omiya Jima" (Great Shrine Island).[20]

The Japanese military occupation of Guam lasted from 1941 to 1944.[21] It was a coercive experience for the Chamorro people, whose loyalty to the United States became a point of contention with the Japanese. Several American servicemen remained on the island, however, and were hidden by the Chamorro people. All of these servicemen were found and executed by Japanese forces in 1942; only one escaped.

The second Battle of Guam began on July 21, 1944 with American troops landing on western side of the island after several weeks of pre-invasion bombardment by the U.S. Navy. After several weeks of heavy fighting, Japanese forces officially surrendered on August 10, 1944.

Guam was subsequently converted into a forward operations base for the U.S. Navy and Air Force. Airfields were constructed in the northern part of the island (including Andersen Air Force Base), the island's pre-WWII Naval Station was expanded, and numerous facilities and supply depots were constructed throughout the island.

Guam's two largest pre-war communities (Sumayand Hagåtña) were virtually destroyed during the 1944 battle. Many Chamorro families lived in temporary re-settlement camps near the beaches before moving to permanent homes constructed in the island's outer villages. Guam's southern villages largely escaped damage, however.

Self-determination[edit]

The immediate years after World War II saw the U.S. Navy attempting to resume its predominance in Guam affairs. This eventually led to resentment, and thus increased political pressure from Chamorro leaders for greater autonomy.

The result was the Guam Organic Act of 1950 which established Guam as an unincorporated organized territory of the United States and, for the first time in Guam history, provided for a civilian government.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, section 307, granted U.S. citizenship to "all persons born in the island of Guam on or after April 11, 1899. In the 1960s, the island's required security clearance for visitors was lifted.

On September 11, 1968, eighteen years after passage of the Organic Act, Congress passed the "Elective Governor Act" (Public Law 90-497), which allowed the people of Guam to elect their own governor and lieutenant governor. Nearly four years later, Congress passed the "Guam-Virgin Islands Delegate" Act that allowed for one Guam delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives. The delegate has a voice in debates and a vote in committees, but no vote on the floor of the House.

Although Public Law 94-584 established the formation of a "locally drafted" constitution (later known as the "Guam Constitution"), the proposed document was rejected by Guam residents in an August 4, 1979 referendum.

In the meantime, Guam's local government had formed several political status commissions to address possible options for self-determination. The following year after passage of the Guam Delegate Act saw the creation of the "Status Commission" by the Twelfth Guam Legislature.

This was followed by the establishment of the "Second Political Status Commission" in 1975 and the Guam "Commission on Self-Determination" (CSD) in 1980. The Twenty-Fourth Guam Legislature established the "Commission on Decolonization" in 1996 to enhance CSD's ongoing studies of various political status options and public education campaigns.

These efforts enabled the CSD, barely two years after its creation, to organize a status referendum on January 12, 1982. 49% of voters chose a closer relationship with the United States via Commonwealth.

Twenty-six percent voted for Statehood, while ten percent voted for the Status Quo (as an Unincorporated territory). A subsequent run-off referendum held between Commonwealth and Statehood saw 73% of Guam voters choosing Commonwealth over Statehood (27%). Today, Guam remains an unincorporated territory despite referendums and a United Nations mandate to establish a permanent status for the island.[citation needed]

Contemporary Guam[edit]

Guam's U.S. military installations remain among the most strategically vital in the Pacific Ocean. When the United States closed its Naval and Air Force bases in the Philippines after the expiration of their leases in the early 1990s, many of the forces stationed there were relocated to Guam.

The removal of Guam's security clearance by President John F. Kennedy in 1963 allowed for the development of a tourism industry. The island's rapid economic development was fueled both by rapid growth in this industry as well as increased U.S. Federal Government spending during the 1980s and 1990s.[citation needed]

On August 6, 1997, Korean Air Flight 801, a Boeing 747-300 bound for Guam crashed into Nimitz Hill while on final approach to the airport, killing 228 of the 254 people on board. [22]

The Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s and early 2000s, which hit Japan particularly hard, severely affected Guam's tourism industry. Military cutbacks in the 1990s also disrupted the island's economy. Economic recovery was further hampered by devastation from Supertyphoons Paka in 1997 and Pongsona in 2002, as well as the effects of the September 11 terrorist attacks on tourism.

There are signs that Guam is recovering from these setbacks. The increased arrivals of Japanese and Korean tourists reflect that country's economic recovery, as well as Guam's enduring appeal as a weekend tropical retreat. U.S. military spending has dramatically increased as part of the War on Terrorism.

Recent proposals to strengthen U.S. military facilities, including negotiations to transfer 8,000 U.S. Marines from Okinawa, also indicate a renewed interest in Guam by the U.S. military. American forces were originally scheduled to relocate from Okinawa to Guam beginning in 2012 or 2013. However, that has been set back due to budget constrains and local resistance to the additional military presence.

"Cosmopolitan" Guam poses particular challenges for Chamorros struggling to preserve their culture and identity in the face of acculturation. The increasing numbers of Chamorros, especially Chamorro youth, relocating to the U.S. Mainland has further complicated both the definition and preservation of Chamorro identity.

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Robert F. Rogers, Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995)

- Paul Carano and Pedro C. Sanchez, A Complete History of Guam (Rutland, VT: C. E. Tuttle, 1964)

- Howard P. Willens and Dirk Ballendorf, The Secret Guam Study: How President Ford's 1975 Approval of Commonwealth Was Blocked by Federal Officials (Mangilao, Guam: Micronesian Area Research Center; Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historical Preservation, 2004)

- Lawrence J. Cunningham, Ancient Chamorro Society (Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992)

- Anne Perez Hattori, Colonial Dis-Ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004)

- Pat Hickey, The Chorito Hog-Leg, Book One: A Novel of Guam in Time of War (Indianapolis: AuthorHouse Publishing, 2007)

- Vicente Diaz, Repositioning the Missionary: Rewriting the Histories of Colonialism, Native Catholicism, and Indigeneity in Guam (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2010)

- Keith Lujan Camacho, Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory, and History in the Mariana Islands (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2011)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Hung, Hsiao-chun; Carson, Mike T.; Bellwood, Peter; Campos, Fredeliza Z.; Piper, Philip J.; Dizon, Eusebio; Bolunia, Mary Jane Louise A.; Oxenham, Marc; Chi, Zhang (2015). "The first settlement of Remote Oceania: the Philippines to the Marianas". Antiquity. 85 (329): 909–926. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00068393.

- ^ Zotomayor, Alexie Villegas (12 March 2013). "Archaeologists say migration to Marianas longest ocean-crossing in human history". Marianas Variety News and Views: 2. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Carson, Mike T. (2012). "History of Archaeological Study in the Mariana Islands" (PDF). Micronesica. 42 (1/2): 312-371.

- ^ a b Pugach, Irina; Hübner, Alexander; Hung, Hsiao-chun; Meyer, Matthias; Carson, Mike T.; Stoneking, Mark (14 October 2020). "Ancient DNA from Guam and the Peopling of the Pacific". bioRxiv: 2020.10.14.339135. doi:10.1101/2020.10.14.339135. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-9BA4-1.

- ^ Vilar, Miguel G.; Chan, Chim W; Santos, Dana R; Lynch, Daniel; Spathis, Rita; Garruto, Ralph M; Lum, J Koji (January 2013). "The origins and genetic distinctiveness of the chamorros of the Marianas Islands: An mtDNA perspective". American Journal of Human Biology. 25 (1): 116–122. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22349. PMC 4335639.

- ^ Peterson, John A. (2012). "Latte villages in Guam and the Marianas: Monumentality or monumenterity?" (PDF). Micronesica. 42 (1/2): 183–208.

- ^ a b Laguana, Andrew; Kurashina, Hiro; Carson, Mike T.; Peterson, John A.; Bayman, James M.; Ames, Todd; Stephenson, Rebecca A.; Aguon, John; Harya Putra, Ir. D.K. (2012). "Estorian i latte: A story of latte" (PDF). Micronesica. 42 (1/2): 80–120.

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992-01-01). Ancient Chamorro Society. Bess Press. ISBN 9781880188057.

- ^ a b Pacific Worlds, Antonio Pigafett's accounts.

- ^ a b c d e f Rogers, Robert (1995). Destiny's landfall: a history of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1678-1.

- ^ [Guam Past and Present by Charles Beardsley], F.H.H Guillemard's accounts.

- ^ [1] Archived 2009-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, Turbulent History of Guam.

- ^ [History of Guam], by Lawrence J Cunningham and Janice J. Beaty.

- ^ a b Guam Online Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, The History of Guam

- ^ [Christina Gumatatotato Lecture], World History and Geography.

- ^ a b Driver, Marjorie (2005). The Spanish Governors of the Mariana Islands. University of Guam. pp. 152, 158. ISBN 1-878453-75-0. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Saniel, Josefa M. (1963). "On Apprehensions and Intentions". Japan and the Philippines, 1868--1898. Quezon City: University of the Philippines. p. 165. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ a b del Carmen, Aniceto Ibáñez (1998). Chronicle of the Mariana Islands. University of Guam. p. 107. ISBN 1-878453-262. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, P. M. (October 1971). "Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870-1914". The English Historical Review. 86 (341): 728–752. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxvi.cccxli.728. JSTOR 563928.

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/archive/wapa/indepth/extcontent/wapa/guides/first/sec4.htm,retrieved 29 December 2009

- ^ Wakako Higuchi, The Japanese Administration of Guam, 1941-1944: A Study of Occupation and Integration Policies, with Japanese Oral Histories (Jefferson McFarland, 2013); online review

- ^ https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR0001.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjXw4GchcLhAhWsZd8KHaMqDvYQFjACegQIBRAB&usg=AOvVaw2wCTFtrQhr7MTJi5nicNROhe

External links[edit]

- allthingsguam A Guam History resource—virtual textbook, virtual workbook and more

- Guam Humanities Council

- Guampedia, Guam's Online Encyclopedia

- War in the Pacific National Historic Park

- The Latte Stones of Guam

- Bisita Guam

- Prefecture Apostolic of Mariana Islands

- Guam Online's History Webpage

- Brief History of Guam's U.S. Naval Hospital

- Senate Resolution 254, 105th Congress Includes brief history of Guam's movement towards self-determination

No comments:

Post a Comment