Dyson sphere

A Dyson sphere is a hypothetical megastructure that completely encompasses a star and captures a large percentage of its power output. The concept is a thought experiment that attempts to explain how a spacefaring civilization would meet its energy requirements once those requirements exceed what can be generated from the home planet's resources alone. Only a tiny fraction of a star's energy emissions reach the surface of any orbiting planet. Building structures encircling a star would enable a civilization to harvest far more energy.

The first contemporary description of the structure was by Olaf Stapledon in his science fiction novel Star Maker (1937), in which he described "every solar system... surrounded by a gauze of light traps, which focused the escaping solar energy for intelligent use."[1] The concept was later popularized by Freeman Dyson in his 1960 paper "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation."[2] Dyson speculated that such structures would be the logical consequence of the escalating energy needs of a technological civilization and would be a necessity for its long-term survival. He proposed that searching for such structures could lead to the detection of advanced, intelligent extraterrestrial life. Different types of Dyson spheres and their energy-harvesting ability would correspond to levels of technological advancement on the Kardashev scale.

Since then, other variant designs involving building an artificial structure or series of structures to encompass a star have been proposed in exploratory engineering or described in science fiction under the name "Dyson sphere". These later proposals have not been limited to solar-power stations, with many involving habitation or industrial elements. Most fictional depictions describe a solid shell of matter enclosing a star, which was considered by Dyson himself the least plausible variant of the idea. In May 2013, at the Starship Century Symposium in San Diego, Dyson repeated his comments that he wished the concept had not been named after him.[3]

Origin of concept[edit]

The concept of the Dyson sphere was the result of a thought experiment by physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson, when he theorized that all technological civilizations constantly increased their demand for energy. He reasoned that if human civilization expanded energy demands long enough, there would come a time when it demanded the total energy output of the Sun. He proposed a system of orbiting structures (which he referred to initially as a shell) designed to intercept and collect all energy produced by the Sun. Dyson's proposal did not detail how such a system would be constructed, but focused only on issues of energy collection, on the basis that such a structure could be distinguished by its unusual emission spectrum in comparison to a star. His 1960 paper "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infra-Red Radiation", published in the journal Science, is credited with being the first to formalize the concept of the Dyson sphere.[2]

However, Dyson was not the first to advance this idea. He was inspired by the 1937 science fiction novel Star Maker,[4] by Olaf Stapledon, and possibly by the works of J. D. Bernal.[5]

Feasibility[edit]

Although such megastructures are theoretically possible, building a stable Dyson sphere system is currently beyond humanity's engineering capacity. The number of craft required to obtain, transmit, and maintain a complete Dyson sphere exceeds present-day industrial capabilities. George Dvorsky has advocated the use of self-replicating robots to overcome this limitation in the relatively near term.[6] Some have suggested that such habitats could be built around white dwarfs[7] and even pulsars.[8]

Variants[edit]

In fictional accounts, the Dyson-sphere concept is often interpreted as an artificial hollow sphere of matter around a star. This perception is based on a literal interpretation of Dyson's original short paper introducing the concept. In response to letters prompted by some papers, Dyson replied, "A solid shell or ring surrounding a star is mechanically impossible. The form of 'biosphere' which I envisaged consists of a loose collection or swarm of objects traveling on independent orbits around the star."[9]

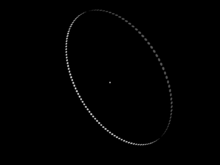

Dyson swarm[edit]

The variant closest to Dyson's original conception is the "Dyson swarm". It consists of a large number of independent constructs (usually solar power satellites and space habitats) orbiting in a dense formation around the star. This construction approach has advantages: components could be sized appropriately, and it can be constructed incrementally.[10] Various forms of wireless energy transfer could be used to transfer energy between swarm components and a planet.

Disadvantages resulting from the nature of orbital mechanics would make the arrangement of the orbits of the swarm extremely complex. The simplest such arrangement is the Dyson ring, in which all such structures share the same orbit. More-complex patterns with more rings would intercept more of the star's output, but would result in some constructs eclipsing others periodically when their orbits overlap.[11] Another potential problem is that the increasing loss of orbital stability when adding more elements increases the probability of orbital perturbations.

Such a cloud of collectors would alter the light emitted by the star system (see below). However, the disruption compared to a star's overall natural emitted spectrum would most likely be too small for Earth-based astronomers to observe.[2]

Dyson bubble[edit]

A second type of Dyson sphere is the "Dyson bubble". It would be similar to a Dyson swarm, composed of many independent constructs and likewise could be constructed incrementally.

Unlike the Dyson swarm, the constructs making it up are not in orbit around the star, but would be statites—satellites suspended by use of enormous light sails using radiation pressure to counteract the star's pull of gravity. Such constructs would not be in danger of collision or of eclipsing one another; they would be totally stationary with regard to the star, and independent of one another. Because the ratio of radiation pressure to the force of gravity from a star is constant regardless of the distance (provided the satellite has an unobstructed line-of-sight to the surface of its star[12]), such satellites could also vary their distance from their central star.

The practicality of this approach is questionable with modern material science, but cannot yet be ruled out. A 100% reflective satellite deployed around the Sun would have an overall density of 0.78 grams per square meter of sail.[13] To illustrate the low mass of the required materials, consider that the total mass of a bubble of such material 1 AU in radius would be about 2.17×1020 kg, which is about the same mass as the asteroid Pallas.[14] Another illustration: Regular printing paper has a density of around 80 g/m2.

Such a material has not yet been produced in the form of a working light sail. The lightest carbon-fiber light-sail material currently produced has a density—without payload—of 3 g/m2, or about four times as heavy as would be needed to construct a solar statite.[15]

A single sheet of graphene, the two-dimensional form of carbon, has a density of only 0.37 mg per square meter,[16] making such a single sheet of graphene possibly effective as a solar sail. However, as of 2015 graphene has not been fabricated in large sheets, and it has a relatively high rate of radiation absorption, about 2.3% (i.e., still about 97.7% will be transmitted).[17][18] For frequencies in the upper GHz and lower THz range, the absorption rate is as high as 50–100% due to voltage bias and/or doping.[17][18]

Ultra-light carbon nanotubes meshed through molecular manufacturing techniques have densities between 1.3 g/m2 to 1.4 g/m2. By the time a civilization is ready to use this technology, the carbon nanotube's manufacturing might be optimised enough for them to have a density lower than the necessary 0.7 g/m2, and the average sail density with rigging might be kept to 0.3 g/m2 (a "spin stabilized" light sail requires minimal additional mass in rigging). If such a sail could be constructed at this areal density, a space habitat the size of the L5 Society's proposed O'Neill cylinder—500 km2, with room for over 1 million inhabitants, massing 2.72×109 kg (3×106 tons)—could be supported by a circular light sail 3,000 km in diameter, with a combined sail/habitat mass of 5.4×109 kg.[19] For comparison, this is just slightly smaller than the diameter of Jupiter's moon Europa (although the sail is a flat disc, not a sphere), or the distance between San Francisco and Kansas City. Such a structure would, however, have a mass quite a lot less than many asteroids. Although the construction of such a massive habitable statite would be a gigantic undertaking, and the required material science behind it is early stage, there are other engineering feats and required materials proposed in other Dyson sphere variants.

In theory, if enough satellites were created and deployed around their star, they would compose a non-rigid version of the Dyson shell mentioned below. Such a shell would not suffer from the drawbacks of massive compressive pressure, nor are the mass requirements of such a shell as high as the rigid form. Such a shell would, however, have the same optical and thermal properties as the rigid form, and would be detected by searchers in a similar fashion (see below).

Dyson shell[edit]

The variant of the Dyson sphere most often depicted in fiction is the "Dyson shell": a uniform solid shell of matter around the star.[20] Such a structure would completely alter the emissions of the central star, and would intercept 100% of the star's energy output. Such a structure would also provide an immense surface that many envision would be used for habitation, if the surface could be made habitable.

A spherical shell Dyson sphere in the Solar System with a radius of one astronomical unit, so that the interior surface would receive the same amount of sunlight as Earth does per unit solid angle, would have a surface area of approximately 2.8×1017 km2 (1.1×1017 sq mi), or about 550 million times the surface area of Earth. This would intercept the full 384.6 yottawatts (3.846 × 1026 watts)[21] of the Sun's output. Non-shell designs would intercept less, but the shell variant represents the maximum possible energy captured for the Solar System at this point of the Sun's evolution.[20] This is approximately 33 trillion times the power consumption of humanity in 1998, which was 12 terawatts.[22]

There are several serious theoretical difficulties with the solid shell variant of the Dyson sphere:

Such a shell would have no net gravitational interaction with its englobed star (see shell theorem), and could drift in relation to the central star. If such movements went uncorrected, they could eventually result in a collision between the sphere and the star—most likely with disastrous results. Such structures would need either some form of propulsion to counteract any drift, or some way to repel the surface of the sphere away from the star.[13]

For the same reason, such a shell would have no net gravitational interaction with anything else inside it. The contents of any biosphere placed on the inner surface of a Dyson shell would not be attracted to the sphere's surface and would simply fall into the star. It has been proposed that a biosphere could be contained between two concentric spheres, placed on the interior of a rotating sphere (in which case, the force of artificial "gravity" is perpendicular to the axis of rotation, causing all matter placed on the interior of the sphere to pool around the equator, effectively rendering the sphere a Niven ring for purposes of habitation, but still fully effective as a radiant-energy collector) or placed on the outside of the sphere where it would be held in place by the star's gravity.[23][24] In such cases, some form of illumination would have to be devised, or the sphere made at least partly transparent, because the star's light would otherwise be completely hidden.[25]

If assuming a radius of 1 AU, then the compressive strength of the material forming the sphere would have to be immense to prevent implosion due to the star's gravity. Any arbitrarily selected point on the surface of the sphere can be viewed as being under the pressure of the base of a dome 1 AU in height under the Sun's gravity at that distance. Indeed, it can be viewed as being at the base of an infinite number of arbitrarily selected domes, but because much of the force from any one arbitrary dome is counteracted by those of another, the net force on that point is immense, but finite. No known or theorized material is strong enough to withstand this pressure, and form a rigid, static sphere around a star.[26] It has been proposed by Paul Birch (in relation to smaller "Supra-Jupiter" constructions around a large planet rather than a star) that it may be possible to support a Dyson shell by dynamic means similar to those used in a space fountain.[27] Masses travelling in circular tracks on the inside of the sphere, at velocities significantly greater than orbital velocity, would press outwards on magnetic bearings due to centrifugal force. For a Dyson shell of 1 AU radius around a star with the same mass as the Sun, a mass travelling ten times the orbital velocity (297.9 km/s) would support 99 (a = v2/r) times its own mass in additional shell structure.

Also if assuming a radius of 1 AU, there may not be sufficient building material in the Solar System to construct a Dyson shell. Anders Sandberg estimates that there is 1.82×1026 kg of easily usable building material in the Solar System, enough for a 1 AU shell with a mass of 600 kg/m2—about 8–20 cm thick on average, depending on the density of the material. This includes the hard-to-access cores of the gas giants; the inner planets alone provide only 11.79×1024 kg, enough for a 1 AU shell with a mass of just 42 kg/m2.[14]

The shell would be vulnerable to impacts from interstellar bodies, such as comets, meteoroids, and material in interstellar space that is currently being deflected by the Sun's bow shock. The heliosphere, and any protection it theoretically provides, would cease to exist.

Other types[edit]

Dyson net[edit]

Another possibility is the "Dyson net", a web of cables strung about the star that could have power or heat collection units strung between the cables. The Dyson net reduces to a special case of Dyson shell or bubble, however, depending on how the cables are supported against the sun's gravity.

Bubbleworld[edit]

A bubbleworld is an artificial construct that consists of a shell of living space around a sphere of hydrogen gas. The shell contains air, people, houses, furniture, etc. The idea was conceived to answer the question, "What is the largest space colony that can be built?"[28] However, most of the volume is not habitable and there is no power source.

Theoretically, any gas giant could be enclosed in a solid shell; at a certain radius the surface gravity would be terrestrial, and energy could be provided by tapping the thermal energy of the planet.[28] This concept is explored peripherally in the novel Accelerando (and the short story Curator, which is incorporated into the novel as a chapter) by Charles Stross, in which Saturn is converted into a human-habitable world.

Stellar engine[edit]

Stellar engines are a class of hypothetical megastructures whose purpose is to extract useful energy from a star, sometimes for specific purposes. For example, Matrioshka brains extract energy for purposes of computation; Shkadov thrusters extract energy for purposes of propulsion. Some of the proposed stellar engine designs are based on the Dyson sphere.[29]

A black hole could be the power source instead of a star in order to increase the matter-to-energy conversion efficiency. A black hole would also be smaller than a star. This would decrease communication distances that would be important for computer-based societies as those described above.[28]

Search for megastructures[edit]

In Dyson's original paper, he speculated that sufficiently advanced extraterrestrial civilizations would likely follow a similar power-consumption pattern to that of humans, and would eventually build their own sphere of collectors. Constructing such a system would make such a civilization a Type II Kardashev civilization.[30]

The existence of such a system of collectors would alter the light emitted from the star system. Collectors would absorb and reradiate energy from the star.[2] The wavelength(s) of radiation emitted by the collectors would be determined by the emission spectra of the substances making them up, and the temperature of the collectors. Because it seems most likely that these collectors would be made up of heavy elements not normally found in the emission spectra of their central star—or at least not radiating light at such relatively "low" energies compared to what they would be emitting as energetic free nuclei in the stellar atmosphere—there would be atypical wavelengths of light for the star's spectral type in the light spectrum emitted by the star system. If the percentage of the star's output thus filtered or transformed by this absorption and reradiation was significant, it could be detected at interstellar distances.[2]

Given the amount of energy available per square meter at a distance of 1 AU from the Sun, it is possible to calculate that most known substances would be reradiating energy in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Thus, a Dyson sphere, constructed by life forms not dissimilar to humans, who dwelled in proximity to a Sun-like star, made with materials similar to those available to humans, would most likely cause an increase in the amount of infrared radiation in the star system's emitted spectrum. Hence, Dyson selected the title "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation" for his published paper.[2]

SETI has adopted these assumptions in their search, looking for such "infrared heavy" spectra from solar analogs. As of 2005[update] Fermilab has an ongoing survey for such spectra by analyzing data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS).[31][full citation needed][32] Identifying one of the many infrared sources as a Dyson sphere would require improved techniques for discriminating between a Dyson sphere and natural sources.[33] Fermilab discovered 17 potential "ambiguous" candidates, of which four have been named "amusing but still questionable".[34][full citation needed] Other searches also resulted in several candidates, which are, however, unconfirmed.[35][36][37]

On 14 October 2015, Planet Hunters' citizen scientists discovered unusual light fluctuations of the star KIC 8462852, captured by the Kepler Space Telescope. The star was nicknamed "Tabby's Star" after Tabetha S. Boyajian — the initial study's lead author. The phenomenon raised speculation that a Dyson sphere may have been discovered.[38][39] Further analysis based on data through the end of 2017 showed wavelength-dependent dimming consistent with dust but not an opaque object such as an alien megastructure, which would block all wavelengths of light equally.[40][41]

Fiction[edit]

The Dyson sphere originated in fiction,[42][43] and it is a concept that has appeared often in science fiction since then. In fictional accounts, Dyson spheres are most often depicted as a Dyson shell with the gravitational and engineering difficulties of this variant noted above largely ignored.[20]

See also[edit]

- Alderson disk – A hypothetical artificial astronomical megastructure

- Dyson spheres in popular culture – Dyson spheres depicted in popular culture

- Dyson tree – Hypothetical genetically-engineered plant capable of growing inside a comet

- Globus Cassus – Art project and book by Swiss architect and artist Christian Waldvogel

- Kardashev scale – Method of measuring a civilization's level of technological advancement, based on the amount of energy a civilization is able to use

- Klemperer rosette – Type of gravitational system

- Matrioshka brain – hypothetical megastructure of immense computational capacity

- Megascale engineering

- Planetary engineering – application of technology for the purpose of influencing the global environments of a planet

- Ringworld – 1970 science fiction novel by Larry Niven

- Star lifting

- Stellar engineering – Hypothetical artificial modification of stars

- Tensegrity – Structural principle based on the use of isolated components in compression inside a net of continuous tension

- Terraforming – Hypothetical planetary engineering process

- Tabby's Star – Star noted for unusual dimming events

References[edit]

- ^ Tate, Karl. "Dyson Spheres: How Advanced Alien Civilizations Would Conquer the Galaxy". space.com. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Freemann J. Dyson (1960). "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infra-Red Radiation". Science. 131 (3414): 1667–1668. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1667D. doi:10.1126/science.131.3414.1667. PMID 17780673. S2CID 3195432.

- ^ "STARSHIP CENTURY SYMPOSIUM, MAY 21 - 22, 2013". 7 July 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^ Dyson, Freeman (1979). Disturbing the Universe. Basic Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-465-01677-8.

Some science fiction writers have wrongly given me the credit of inventing the artificial biosphere. In fact, I took the idea from Olaf Stapledon, one of their own colleagues

- ^ Sandberg, Anders (2012-01-02). "Dyson FAQ". Stockholm, Sweden. § 3. Was Dyson First?. Archived from the original on 2012-11-21. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (2012-03-20). "How to build a Dyson sphere in five (relatively) easy steps". Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ^ Semiz, İbrahim; Oğur, Salim (2015). "Dyson Spheres around White Dwarfs". arXiv:1503.04376 [physics.pop-ph].

- ^ Osmanov, Z. (2015). "On the search for artificial Dyson-like structures around pulsars". Int. J. Astrobiol. 15 (2): 127–132. arXiv:1505.05131. Bibcode:2016IJAsB..15..127O. doi:10.1017/S1473550415000257. S2CID 13242388.

- ^ F. J. Dyson, J. Maddox, P. Anderson, E. A. Sloane (1960). "Letters and Response, Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation". Science. 132 (3421): 250–253. doi:10.1126/science.132.3421.252-a. PMID 17748945.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Dyson FAQ: Can a Dyson sphere be built using realistic technology?". Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "Some Sketches of Dyson Spheres". Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ "Sunlight Exerts Pressure". Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- ^ a b "Dyson Sphere FAQ: Is a Dyson sphere stable?". Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ a b Sandberg, Anders. "Is there enough matter in the Solar System to build a Dyson shell?". Dyson Sphere FAQ. Retrieved 2006-08-13.

- ^ Clark, Greg (2000). "SPACE.com Exclusive: Breakthrough In Solar Sail Technology". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2006-01-14. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- ^ Kakran, Mitali (2011), "Graphene: The New Wonder Material!!!", IET present around the world (PDF), retrieved 2013-03-23

- ^ a b "Graphene properties". www.graphene-battery.net. 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- ^ a b Apell, S. P; Hanson, G. W; Hägglund, C (2012). "High optical absorption in graphene". arXiv:1201.3071 [physics.optics].

- ^ Dinkin, Sam (2006). "The Space Review: The high risk frontier". Thespacereview.com. Retrieved 2006-03-18.

- ^ a b c "Dyson FAQ: What is a Dyson Sphere?". Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ "NASA Sun Fact Sheet". Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ "Order of Magnitude Morality". Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Drashner, Todd; Steve Bowers; Mike Parisi; M. Alan Kazlev. "Dyson Sphere". Orion's Arm. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Badescu, Viorel; Richard B. Cathcart. "Space travel with solar power and a dyson sphere". Astronomy Today. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ "Fermi Conclusions". Archived from the original on 2007-09-23. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ "Dyson FAQ: How strong does a rigid Dyson shell need to be?". Retrieved 2006-03-08.

- ^ Search WaybackMachine for the 14th of June 2011 copy of {{cite web |url=http://www.paulbirch.net/SupramundanePlanets.zip |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2006-03-02 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20060627074700/http://www.paulbirch.net/SupramundanePlanets.zip |archivedate=2006-06-27 }}

- ^ a b c Sandberg, Anders. "Other Dyson Sphere-Like Concepts". Dyson Sphere FAQ. Retrieved 2006-08-13.

- ^ "Stellar engine". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ^ Kardashev, Nikolai. "On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations", The search for extraterrestrial life: Recent developments; Proceedings of the Symposium, Boston, MA, June 18–21, 1984 (A86-38126 17–88). Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1985, p. 497–504.

- ^ Carrigan, D. (2006). "Fermilab Dyson Sphere search program". Archived from the original on 2006-03-06. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- ^ Shostak, Seth (Spring 2009). "When Will We Find the Extraterrestrials?" (PDF). Engineering & Science. 72 (1): 12–21. ISSN 0013-7812. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-15.

- ^ Carrigan, Richard; Dyson, Freeman J. (2009-05-15). "Dyson sphere at Scholarpedia". Scholarpedia. 4 (5): 6647. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.6647.

- ^ Carrigan, D. (2012). "Fermilab Dyson Sphere search program". Archived from the original on 2006-03-06. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ^ Dick Carrigan (2010-12-16). "Dyson Sphere Searches". Home.fnal.gov. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- ^ Billings, Lee. "Alien Supercivilizations Absent from 100,000 Nearby Galaxies". Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Infra digging: Looking for aliens: The search for extraterrestrials goes intergalactic". The Economist. 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

Fifty [galaxies] were red enough to be hosting aliens gobbling up half or more of their starlight.

- ^ Andersen, Ross (13 October 2015). "The Most Mysterious Star in Our Galaxy". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Williams, Lee (15 October 2015). "Astronomers may have found giant alien 'megastructures' orbiting star near the Milky Way". The Independent. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Boyajian, Tabetha S.; et al. (2018). "The First Post-Kepler Brightness Dips of KIC 8462852". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1). L8. arXiv:1801.00732. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853L...8B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aaa405. S2CID 215751718.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (3 January 2018). "Mystery of 'Alien Megastructure' Star Has Been Cracked". National Geographic. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ Olaf Stapledon. Star Maker

- ^ J. D. Bernal, The World, the Flesh & the Devil: An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul

External links[edit]

| Look up Dyson sphere in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dyson sphere. |

- Dyson sphere FAQ

- Toroidal Dyson swarms simulations using Java applets

- FermiLab: IRAS-based whole sky upper limit on Dyson spheres, with a notable appendix on Dyson sphere engineering

- Dyson sphere at Memory Alpha (a Star Trek wiki)

- Freeman Dyson

- Astronomy projects

- Exploratory engineering

- History of science

- Hypothetical astronomical objects

- Hypothetical technology

- Megastructures

- Philosophy of science

- Philosophy of technology

- Energy development

- Solar power

- Proposed space stations

- Science fiction themes

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence

- Space colonization

- Thought experiments

No comments:

Post a Comment